Kabuki: An Encounter with Japanese Theatre

If you are interested in Japanese theatre, then you will know Kabuki, a classical Japanese dance-drama. Kabuki theatre is known for its unique stylization and for the elaborate make-up worn by some of its performers.

Kabuki has been recognised by UNESCO as possessing intangible cultural heritage, but up until the modern day, this value was largely inaccessible for foreigners.

For over 220 years, ending in 1853, Japan was a closed country, known as sakoku. This meant the western world was culturally distanced from Japan. The intention behind this isolation was to protect Japanese culture from religious interference, most notably Christianity, which had found a steady growth in Japan from Spanish and Portugese colonists. Under sakoku, Japanese culture was withdrawn from the world stage and performed a sort of fermentation: with no outside influence, it thrived under its own ignition.

Today, the Western world is lucky to have access to Japanese culture’s enigmatic charm, and one of the ways in which we can see the most is through cultural vehicles such as theatre. Today, Sabukaru intends to take you on a journey through Kabuki theatre, so that we can perform the humble task of opening the window on an unmistakably Japanese artform.

Kabuki: An Encounter with Japanese Theatre

There are four main types of theatre in Japan.

We have puppet theatre, known as Bunraku, classic theatre known as Noh, Kabuki, and a fourth, more modern version which serves as a medium for western plays, known as Shingeki.

Kabuki

Bunraku

Noh

Shingeki

Kabuki is distinguished from Noh by its focus on dance, clothing and gestures.

In Noh, storytelling is done through music, and it was primarily an artform for the samurai class.

Kabuki, developing three centuries after Noh, was presented for the common people, and therefore took a progressive step and took itself less seriously. Whereas noh was sophisticated and refined, Kabuki was flamboyant and fun, and served to unify and engage multiple classes throughout Japan by uniting them through entertainment.

With its emphasis on gestures rather than words, Kabuki spoke to the human experience visually, and built on diverse and universally human themes in much the way that Shakespeare or the Western Classical myths did. In kabuki, allegories of revenge, love and jealousy occur through numerous contemporary characters and aesthetic mediums.

Three Kabuki Actors, Late Edo period, circa 1847-1852 by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Kabuki is intimately connected to the Edo era of Japan, beginning in 1603. Each type of Japanese theatre reflects the formation of the social structure of the country, and with the Edo period, urban Japan found itself submerged in leisure time. The populace were engaged in a search for enjoyment, known as the floating world (ukiyo), where an aesthetic quality brought meaning to their lives. This newly-found freedom to enjoy catalysed the creation of kabuki.

The origins of kabuki begin with a priestess known as Okuni.

She gathered numerous misfits, often prostitutes, and formed an all-female troupe, a shibai, that found support in one another, and as Okuni taught these rogues the basics of dance, acting, and singing, they forged the origins of Kabuki by hosting eccentric and rowdy performances that lacked direction, but oozed beauty and intrigue.

Okuni’s teachings had origins in a dance called nembutsu-odori, which she imbued with a unique sensuality and innuendo.

Unfortunately, this sowed the seeds for public outcry, and whilst the provocative nature had the capacity to draw significant crowds, during a moral reform in 1629, shibai and thus women, were banned from performing kabuki.

Following the ban of women, young eccentric men in cross-dress, known as yaro-kabuki, took on the main acting roles in kabuki, but the police eventually banned this group due to similar associations with prostitution and scandal. Eventually, the authorities settled on only allowing older men to perform as actors in kabuki, which is a tradition that holds to this day.

Following these periods of scandal, kabuki slowly refined itself, and internalised overtly sexual themes, whilst developing into a medium that explored historical drama. Soon, the contents of kabuki shows became anything that highlighted feudal Japan, with classical notions of heroes, villains and vassalism. Additionally, kabuki explored the contemporary lives of lower class merchants and vagabonds.

A scene from the kabuki play ‘Sukeroku’,

A famous play called Sukeroko serves to highlight these latter themes. It is a tale of deceit and treachery involving the lives of prostitutes, sake-sellers and washed up samurais, who attempt to solve a controversial partricide.

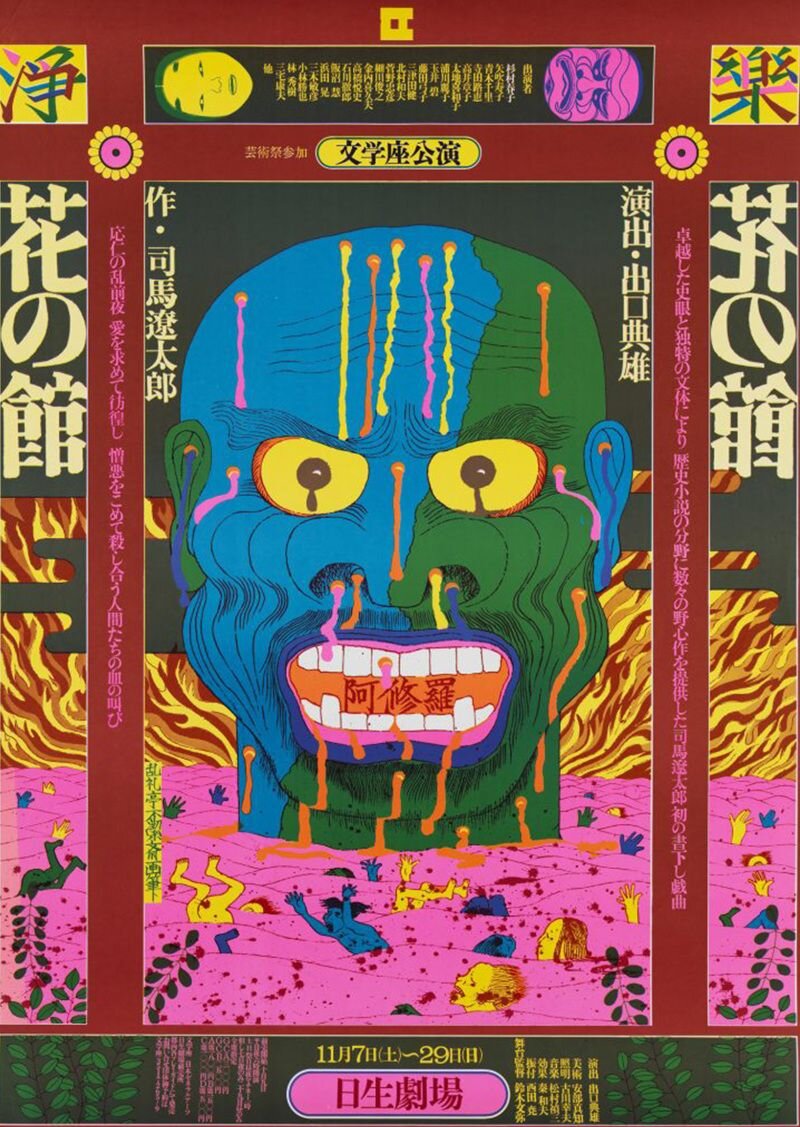

Another play, Keisei Hangonko, explores themes equally as universal, but more abstract. It attends to the role of the artist in the world, touching on the struggle that artists face in contextualising their work, eventually culminating in societal rejection. In a uniquely Japanese affair, the artist in question commits a ritual suicide after being humilited, before which, in order to ensure the timeless touch of his work on the world, he paints a portrait on a stone. Through means that remain mysterious, his portrait imprints on the stone, and consequently, his place in the world is solidified and, post-death, he becomes as permanent as the rock itself.

Since its inception, the kabuki genre has gone through numerous transformations.

In 2014, a group of kabuki actors sought to modernise the genre, acknowledging that despite its rich cultural heritage, kabuki seemed distant from many of the youngest generations. This adaptation of kabuki is called ‘Super Kabuki’, allows women, and uses manga and anime to breach new audiences. For example, super kabuki has used Shonen Jump manga such as One Piece as a base, and also recreates traditional plays using aerial stunts, projections and modern lighting techniques.

Super Kabuki

Despite inspiring heated debate, super kabuki serves to keep the essence of kabuki alive. It breathes entertainment, expresses emotion and is seeped in allegory. Further, modernisations of kabuki continue the tradition of flamboyant and expressive dress, and outfits often serve to tell us as much about a character as their gestures. More so, in fact, as subtle pieces of clothing even allude to intimate details of a character, such as their person inclinations, or even their fates.

The clothing of kabuki was so inspirational to various westerners on their visits to Japan, that Yves Saint Lauren and Pierre Berge eventually culminated their fifty year love affair with Japan in a 2012 exhibition showcasing the clothing of kabuki, and over the years absorbed countless inspiration from the traditional dress.

Mind you, the western influence of kabuki is about far more than clothes. Russian avant-garde director, Meyerhold, developed a model of acting theory called biomechanics.

Meyerhold used prints by the Japanese artist Hokusai to study the expression of kabuki actors.

Hokusai immortalised many famous kabuki plays in woodblock carvings, and these caricature-like vehicles of expression served to uproot Meyerhold’s naturalist teachings, which sought to recreate theatre as closely as possible to real life.

Meyerhold knew that in traditional theatre, the fourth wall was always present: the audience and the actors are two different entities, which limits the emotional response that the former can receive. The essence of biomechanics is in using the body to its fullest to convey deep emotions that the subtlety of naturalist theatre loses.

By paying attention to kabuki, Meyerhold realised that within theatre, the body should be engaged in ways above and beyond the norm to solicit the largest emotional engagement.

The influence of kabuki can be seen significantly in Japanese film.

In The Throne Of Blood, Miki and Washizu approach the witch (who wears a noh mask)

Kurosawa’s The Throne of Blood (1957)

The first Japanese films were simply kabuki performances of historical dramas turned into movies, despite the fact that cinema appeared in Japan at around the same time as in other countries.

Strangely, this disposition towards filming kabuki gave Japanese cinema a stagnated start. When Japanese cinema got into full swing, kabuki and noh influences were impossible to shake.

The landmark film, Throne of Blood (1957) by Akira Kurosawa transposed the plot of Macbeth into feudal Japan and featured poignant ritual performances influenced by noh. Further, Kurosawa used the masks from noh to direct the imagination of the actors, by using it as a guide for expressing who their character really was.

The tradition of kabuki runs through all the actors movements, as no motion is wasted. Every single movement is a vehicle for expression - there is nothing superfluous. Each directive choice is well thought through and attentive, which ensures that each action and scene is justified with meaning.

To drive home this final point, we need to remember that the core of kabuki is aesthetics.

Fujito at Shibuya Noh

The audience can pick up on overt clues from movement, clothing, gesture and expression, that convey emotion and beauty, eventually resulting in intense feelings that transcend language.

An essential theory behind kabuki is that the audience and the actors are inseparable, and therefore the bulk of kabuki acting is improvised, allowing the actors to feed off audience response.

The necessary exaggerations of kabuki movement serves to catalyse as much response as possible.

Finally, as our guide to kabuki concludes, we feel that it is fitting to include a list of theatres in Tokyo where kabuki thrives.

Where to experience Kabuki in Tokyo

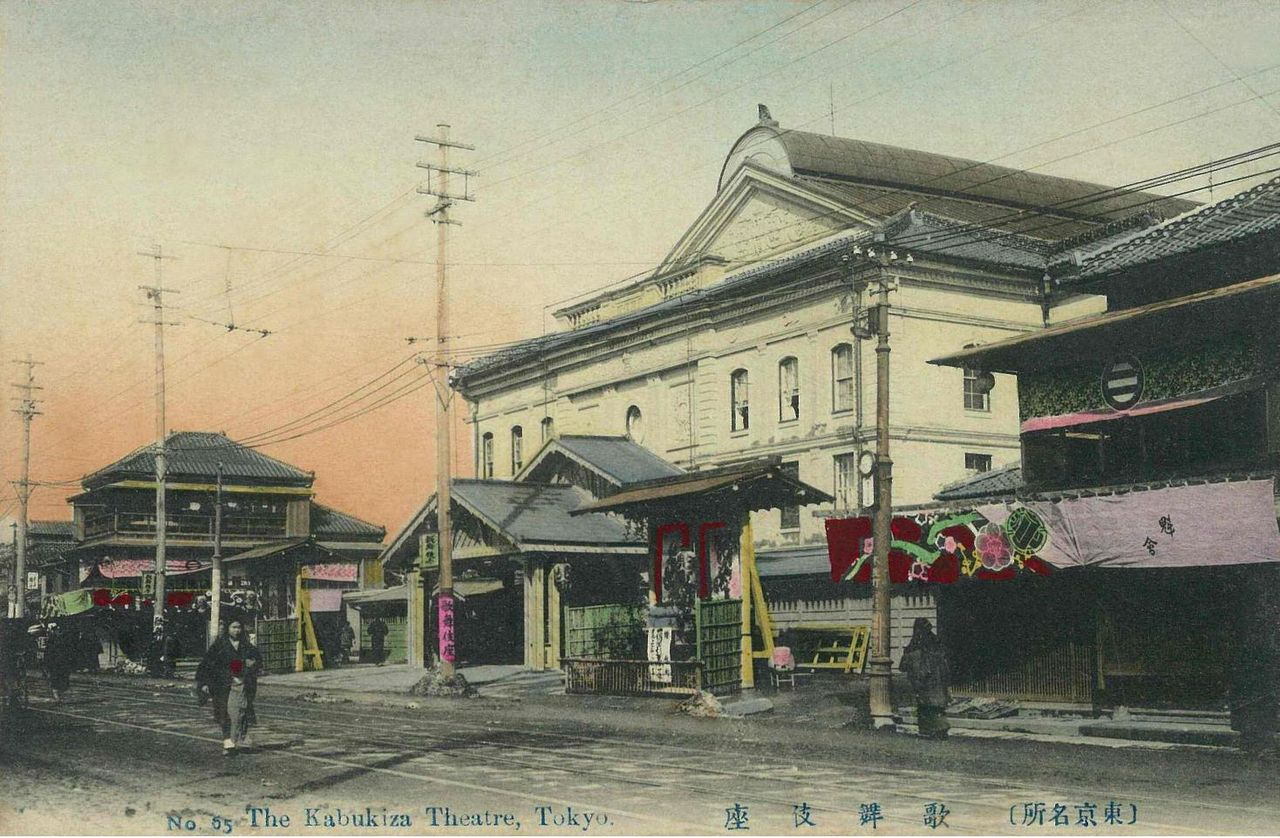

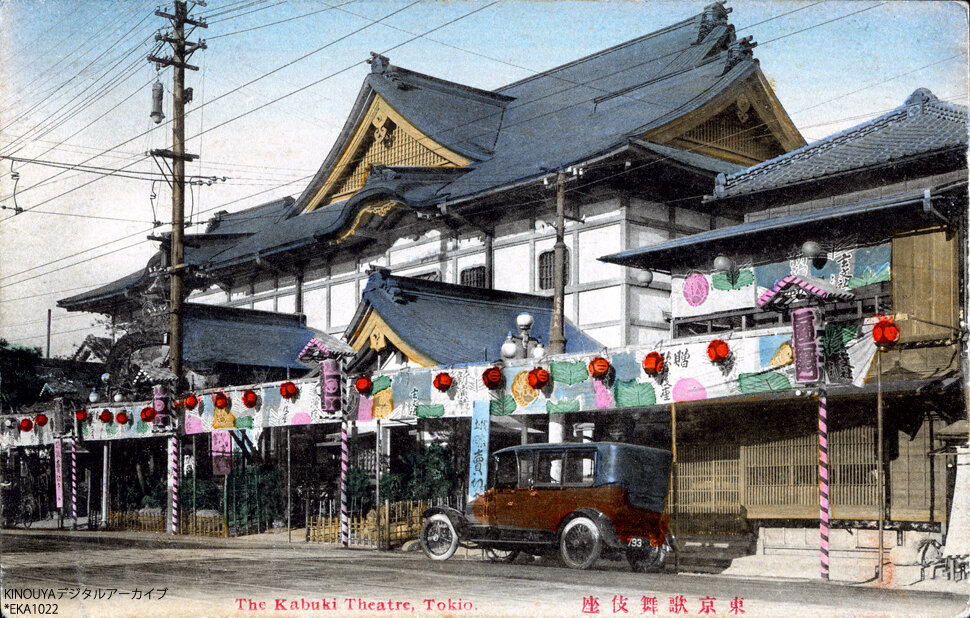

Nowadays the main theatre for Kabuki in Tokyo is Kabukiza. Here you can get a guide with descriptions of plays and their historical backgrounds. It might sound like a primitive touristic tip, but we would really advise you to get a guide once you go there. Even Japanese people need guides!

Kabukiza Theatre (Ginza)

4 Chome-12-15 Ginza, Chuo City, Tokyo 104-0061, Japan

New National Theatre Tokyo (Honmachi, Shibuya, Tokyo)

1 Chome-1-1 Honmachi, Shibuya City, Tokyo 151-0071, Japan

A theatre for viewing contemporary performing arts.

Suehirotei (Shinjuku)

3 Chome-6-12 Shinjuku, Shinjuku City, Tokyo 160-0022, Japan

Suehirotei gives rakugo performances, Rakugo is a 400-year-old tradition of comic storytelling in Japan.

Imperial Theatre

3 Chome-1-1号 Marunouchi, Chiyoda City, Tokyo 100-0005, Japan

The Imperial Theatre is the first theatre which was built according to the European standards.

National Noh Theatre Tokyo (Sendagaya)

4-18-1 Sendagaya, 渋谷区 Shibuya City, Tokyo 151-0051, Japan

Setagaya Public Theatre (Setagaya)

4 Chome-1-1 Taishido, Setagaya City, Tokyo 154-0004, Japan

Za-koenji Public Theatre (contemporary performing arts)

2 Chome-1-2 Koenjikita, Suginami City, Tokyo 166-0002, Japan

Shimbashi Enbujo Theatre

6 Chome-18-2 Ginza, Chuo City, Tokyo 104-0061, Japan

Cerulean Tower Noh Theatre

Japan, 〒150-0031 Tokyo, Shibuya City, Sakuragaokacho, 26−1 地下2階

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Carina Scherpenisse is an aspiring writer based in Berlin, Germany. She gets inspiration from the theatre cause she believes that theatre is a quintessential part of every culture. Now she’s focused on Japanese culture and working on her own play drafts.

Jacob is a chef and writer based in Manchester, England. He specialises in environmental consultancy relating to food and fashion.