When Modern Modern Aesthetics Meet Not-so-Modern Anime, Manga, Video Games: Balletcore and Corpcore

Let’s face it: the current fashion landscape is ruled by trends, now more than ever before. Additionally, trends change more often and much faster, now more than ever before. The transformation has only been expedited with modern, algorithmically-optimized apps and sites like Instagram, Pinterest, Tiktok, and even Roblox, as people find new ways to create, discuss and be inspired by fashion online. That said, it’s becoming apparent that Gen-Z’s obsession with the “core”-ification and categorization of fashion aesthetics is more than simply a crisis of personal style/identity and attention spans.

In recent years, communities surrounding various fashion aesthetics, from the super mainstream to hyper-niche subcultures, have dominated every corner of the internet. More often than not, the dissemination, influence and staying-power of these aesthetics speak to a larger cultural moment within our society. For example, the spike in interest around outdoor-focused activities and the related aesthetic of gorpcore, as a result of the pandemic’s effect on gathering types and sizes, comes to mind. As many fashion analysts and enthusiasts have noted, not all trends are built to last. With social media and short-form content reigning supreme, it feels like modern trend cycles have a viciously short lifespan. Because of this, when a trend does stick around, it’s worth a little examining. And if you’ve been keeping up with fashion, you know that Balletcore is clearly here for the long-haul.

Since 2020, the infusion of ballet’s aesthetic elements in fashion has only increased, season after season. From tulle skirts to ballet flats, fashion’s buzziest brands– including MiuMiu, Maison Margiela, and of course, Sandy Liang– have taken direct inspiration from the dance studio or stage. But the industry’s flirtation with the graceful yet grueling athletic art form started long before the recent rise on the runway and social media. Though fashion and ballet have had an intrinsic connection for what feels like forever, it wasn't until the 20th century, when the pioneers of modern fashion like Coco Chanel, Jeanne Lanvin, Elsa Schiaparelli and later Christian Dior, started drawing inspiration from ballet for their collections, referencing dance signatures like full skirting, tulle fabric and dreamy colour palettes. Patricia Mears, deputy director at New York City’s The Museum at FIT (Fashion Institute of Technology) and curator of the museum’s 2020 exhibit, “Ballerina: Fashion’s Modern Muse” says the invigoration of ballet culture in the ‘20s and ‘30s in the West sparked a fascination with ballet dancers themselves, leading to an early version of what one might call balletcore. “Women designers in particular began using class and rehearsal wear as a foundation for easy, knitted separates. It was a fascinating phenomenon.” Since then, fashion has played a role in the evolution of ballet and, as we can see today, vice-versa.

The fascination with ballet has been well-documented within art and culture, not only in the West, but in the East as well. While Natalie Portman’s haunting portrayal in Black Swan may be the most notable, eerily similar parallels and references can be found in Satoshi Kon’s 1997 Perfect Blue, released some 15 years earlier. Perfect Blue expertly encapsulates the themes of beauty, perfection and pressure associated with high-level performance for young women entertainment industries through its protagonist, idol turned actress, Mima. In pursuit of her dream, she struggles in a world with a deep, sometimes violent desire to control, objectify and exploit her. Blurring the lines between reality and fantasy, the ballerina-inspired costume of Mima’s idol days remains a recurring emblem in her life, taking on new, twisted, symbolic meaning as she struggles with depression, delusion, and depersonalization.

Similarly, Princess Tutu (2002) juxtaposes its sweet, cute, feminine ballet-infused aesthetics against its dark fantasy story. Inspired by fairytales by the likes of Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm, Junichi Sato uses an authentic portrayal of ballet as his backdrop to explore themes of friendship, love, pain and innocence. Full of realistic ballet fashion designs, dance movements and music, Princess Tutu is a beautiful love letter to the art of ballet, classical music and girlhood. The shoujo genre, which is generally aimed at girls and thus often explores their experiences, has a particular, understandable fascination with ballet. And those aesthetic and thematic influences can be found in tons of anime and manga. There is no shortage of frilly tutus, opaque tights, oversized bows and the colour pink in series like Sailor Moon, Cardcaptor Sakura and Madoka Magica. And much like their predecessor Princess Tutu, they each explore nuanced themes associated with girlhood in their own way.

As an alternative to the magic and whimsy of much of the Shojo genre, animanga’s fashion legend Ai Yazawa’s offers timeless fashion inspiration with her Josei (aimed at young women) cult-classic, Paradise Kiss. Published in 1999, with its anime adaptation airing in 2005, it's no surprise that a story following the lives of creative young fashion students in Tokyo’s most stylish hubs would be ripe with style inspiration, lifting fashion to new heights within the medium. The character Miwako’s cute, sweet, almost-childlike demeanor is amplified through her style. Her bouncy pink curls are only outshone by the fluffy layers of lace and frills that make up her character’s eye-catching design language.

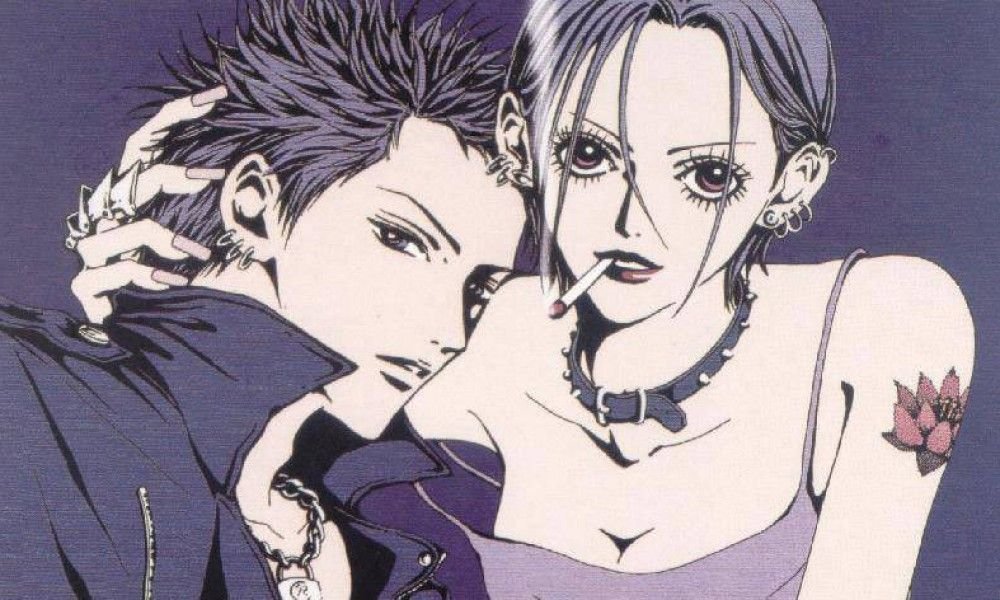

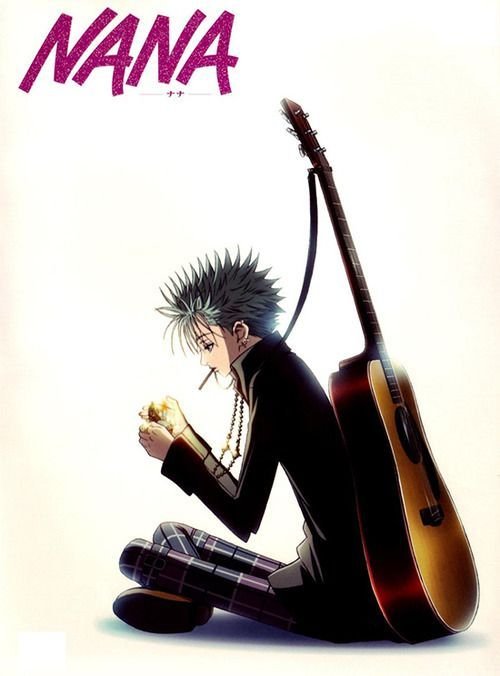

Then, just over a year later, Ai Yazawa fed fashion fanatics once again, publishing what many would consider her magnus opus: Nana in 2000. Nana’s bittersweet story is as stirring as it is stylish. The tale follows the lives of two very different girls who share the same name and initially, not much else. Nana Komatsu, known more familiarly as Hachi, starts the series as a cute, clumsy, plucky insecure girl looking for direction, connection and excitement in her life. Her aesthetic is reflective of her journey as a character as she struggles to work through the complex emotions and experiences many of us would associate with the first tastes of adulthood. Early chapters/episodes show Hachi in girly ensembles that feature classic balletcore elements like sweetheart necklines, soft pastel colours, juliet puff sleeves, ballet flats, legwarmers, dainty printed scarves and skirts.

But as Hachi works through romance, sex, betrayal, unhealthy coping mechanisms and patterns, educational/professional uncertainties and friendship, we start to see a change. And this transition is expertly, albeit subtly, shown through Hachi’s aesthetic, as blazers, blouses and pencil skirts are added to her wardrobe. As Hachi builds a better understanding about her wants, needs and future, she begins to channel a more mature femininity. Romanticizing her life and work through fashion helps her as she grapples with the many anxieties of growing up. Like so much of the Nana series, Hachi’s journey remains deeply relatable. Its bittersweet, authentically human portrayal of an adult adolescence speaks to the confusion and pressure of young adulthood we all experience, no matter the generation or culture.

Balletcore is far from the only contemporary trend on centre stage in Nana. And it certainly isn’t the only trend reflective of our/gen-z’s current climate of uncertainty. After years of girlmath, and girldinner, the sartorial shift feels almost inevitable. Enter: Corpcore and the Office Siren.

Though some might look at fashion’s current corporate fetish as the natural evolution from various Girl™ trends to womanhood, it may be more accurate to look at corpcore as a sort of extension of the girlhood trend. For Gen-Z, many of whom are just beginning to enter the workforce and have never even seen a cubicle, tight-fitting pencil skirts, sheer tights, tailored blazers and other components of 90s and early 2000s corporatewear offer a chance to re-envision the girlboss for modern times. That re-envisioning is less about functional, office-appropriate clothing and more focused on channeling the energy of a smart, sexy, powerful working woman straight out a y2K rom-com (think Gisele Bündchen’s character in The Devil Wears Prada, Lucy Liu’s iconic leather outfit in Charlie’s Angels, Samantha Jones, etc). Like balletcore, corpcore is another way people are romanticizing their lives, reclaiming elements of their childhood and repurposing nostalgic dreams of work culture in a post-pandemic world.

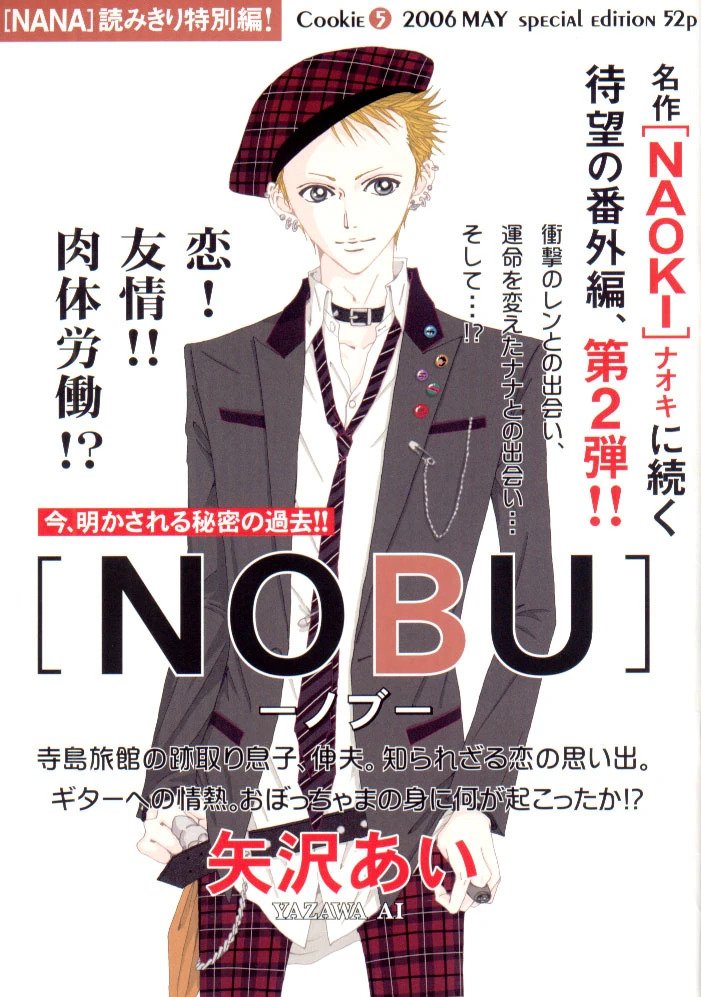

Nana Osaki, the other Nana, exists as the perfect foil to Hachi. Despite sharing the same name, home and age, the edgy, cool, punk-rocker represents a completely different brand of girlhood, and feminitity. Unlike Hachi, Nana starts the series off much more sure of who she is and what she wants. However, that’s not to say she’s got it all figured out. And much like Hachi, her personal style offers us a further look into her psyche as she works through her own contentions and concessions around love, friendship and rock n’ roll success. An undoubtable star, Nana is as intriguing as she is intimidating. Her chic, bold wardrobe further underlines this. In addition to her love for leather, cigarettes and Vivienne Westwood, Nana pulls inspiration from a corporate dress code, adding collared white button-up shirts, neckties and chic blazers to the mix. Through this classic blending of seemingly-opposing styles, Nana presents a serious, sexy, playful interpretation of a confident, mature young woman who manages to stay connected to her youthful exuberance. This corpcore infusion can also be seen in other characters from the stylish ensemble class, such as Junko, Nobu and Yasu.

Discussion of the corpcore trend without the mention of another charming and mysterious Black haired beauty would be incomplete. Bayonetta (real name Cereza) is the main protagonist of the Bayonetta series, the urban fantasy action-adventure video game series created by Hideki Kamiya, released for Xbox360 and the Playstation3 in 2009. With much of the corpcore and office siren trends starting or surrounding the style of 90s and 2000s eyewear now coined “bayonetta glasses”, her sexy, smart, badass style has leapt from the virtual world to ours.

Not long after Bayonetta’s release, the game Catherine was released for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in 2011. From the minds that brought us the Persona Game Series, Catherine is part anime, part visual novel, part puzzle game with an intriguing plot focused on love and betrayal.

Anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion, Chainsaw Man and Psycho Pass have no problem putting strong, self-actualizing, working women at the forefront of their stories. Complex and flawed characters like Ritsuko, Misato, Makima and the women of Psycho Pass each embody aspects of the office siren spirit. And their cult-following shows us just how cool, captivating and capable women like them can be.

With all of these aesthetics and cores, it’s very easy to reduce it all to silly little gen-z trends, but certain recurring themes, political undertones, and the continued economic uncertainty make clear an almost subconscious desire to reclaim youth, femininity, futurities and power through fashion in an age where so many feel powerless. As the world continues spinning through these harsh, unprecedented times, fashion and aesthetics can provide the escapism so many of us are looking for. It's that similar brand of escapism that draws people to anime and manga, whether it's a recent, original anime production or a manga series published almost 30 years ago. When modern aesthetic trends like Balletcore and Corpcore can pull references from various Japanese media across decades, we see just how many connections to our collective experience can be shared through any medium of storytelling, whether that’s fashion, anime, manga or video games.

With the upcoming release of the adidas Taekwondo, a versatile, timeless silhouette befitting the visual language of both balletcore and corpcore, sabukaru, alongside adidas Tokyo, shot with none other Shioli Kutsuna (Deadpool 2, Deadpool & Wolverine, Sanctuary, Invasion and more) to explore the common ground across current trends like balletcore and corpcore and anime/manga.

Written by Vanessa Fajemisin

adidas Taekwondo Editorial credits:

Creative Director: Anisha Kapoor

Executive Producer/Art Director: Natsuki Ludwig

Producer: Effy Zhang

Production Manager: Kei Honda

Production Assistants: Maya Lowery & Ryosuke Oki

Talent: Shioli Kutsuna

Photographer: Hiroshi Manaka

Photo assistant: Ishihara

Retoucher: Mari Obara

Videographer: Yuya Noda

Stylist: Ayaka Endo

Hair stylist: Hayate Maeda

Make-up artist: Yuka Hirac

Prop master: Tei

Graphic Designer: Patryk Kulig

A Bianco Bianco Tokyo Production.