Uniforms and Street Style - Fitting in With the Masses or Standing Out in a Crowd

Manoeuvring through the streets of Shibuya, my eyes, ears and nose are assaulted by a multitude of sights, sounds, and smells. But as a Londoner I’m semi-trained for this. Elbows at the ready, I take a step and—

—my breath catches in my throat, I’m stopped in my tracks by a pair of white huaraches. Perplexed by the woven white leather sandals from Mexico, and what they are doing in the streets of Tokyo in the pouring rain at 9pm on a Tuesday, my elbows slowly backed down.

Tashi Lahmu is a Tibetan-British writer and creative, who has recently joined Sabukaru, her writing focuses on fashion and culture. Here she shares her thoughts on one of her first days in Tokyo, transporting you to the infamous Shibuya Crossing and giving you a rare insight into the Sabukaru team and their sartorial practises.

These shoes that were once a symbol of resistance for Mexican immigrants in the US, a tool to counter racist narratives and represent their culture, I wondered what they were doing being taken for a walk across Scramble Crossing by a middle aged Japanese man? As I continued to look up I wasn’t getting any clues. Lavishing over them were the upturned cuffs of a pair of medium-wash denim dungarees. These were buckled over a graphic hoodie and to complete the look, a straw cowboy hat adorned with feathers and crocheted pieces. Fabulous.

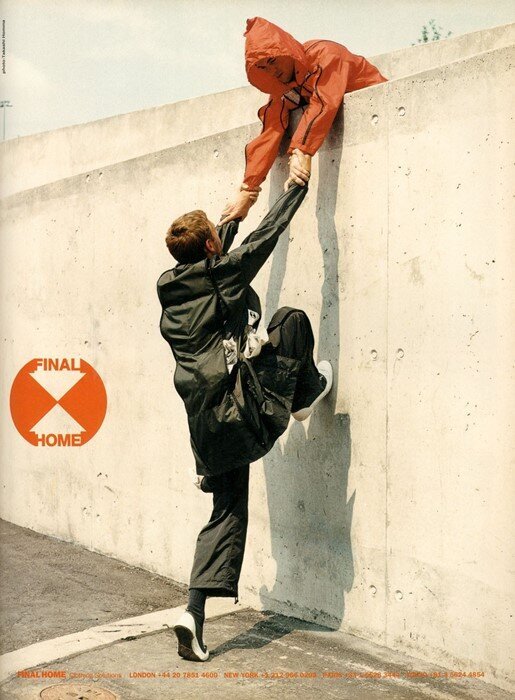

If I had kept paying such close attention I would have been stuck in the middle of Shibuya all night. But as is always the case, in this city of juxtapositions, the number of Uniqlo mannequins and jorts-wearing tourists just about even out the vibrant and eclectic styles. Amongst these crowds there is also another group of dressers. Eclipsing the dazzling streets of Tokyo are those stream-lined city slickers dressed head-to-toe in black. Even on opposite sides of the street they seem to have a telepathic connection. There is a sense of unity in their uniformity. I’m reminded of Peter Do’s approach at Helmut Lang to create a system of dressing in response to the “chaos within fashion”; an attitude that reflects Helmut’s original desire to counter the opulence of the ’80s.

Peter Do’s ‘system of dressing’

There is something about this look that teeters between sophisticated intimidation and the communist desire to suppress individuality. Okay, now that might seem to be quite the jump. It might also be a good time to say that many of us at Sabukaru, cough-cough namely the editor-in-chief, are fans of the everyday all-black uniform. But this doesn’t mean we can’t interrogate it, particularly as we are based in the city of neon lights and unique street style.

When you think about uniforms, what comes to mind?

Now, writing this in Japan I can’t help but think about the festishism of school uniforms, but also their cultural significance in anime such as Neon Genesis Evangelion, My Hero Academia, or, of course, Sailor Moon. Then go almost 2000 miles West and you have the history of the Mao suit. During this dark period of China’s history, the uniformity of the khaki green, navy blue, or grey suits represented a controlled homogenous identity under communist rule. But then travel further West and you have the business suit. A look that has come to define the Western cityscape. For the fashionistas reading this I’m not talking about an Yves Saint Laurent ‘Le Smoking Suit’, a feat of tailoring that exudes coolness. Instead bring to mind a navy pinstripe two piece, worn by a slightly balding businessman with leather briefcase in hand. Now you get the image.

An example of the Mao Suit worn by communist leaders in the 1950s.

The iconic image of an androgynous model in ‘Le Smoking Suit’ shot by Helmut Newton.

During a time when cities like London and New York were developing into the business capitals they are today. The German sociologist and philosopher, Georg Simmel, began to question what the sudden rise of the business suit meant in the city. The changing landscape from rural to urban, brought many new sights, sounds, and smells (much like my first experience on Shibuya Crossing). People began to move in wider social circles and the mass reaction to these changes was a sudden intense awareness of oneself and identity. Simmel wrote that the business suit became an armour against the rise of individualism and ego. The simple, monotonous two-piece provided a sense of calm in the overstimulating city life.

But the uniformity and dull colours remind me of the communist desires of Mao or Stalin and his “iron curtain”, that banned clothing imports and fashion magazines, to suppress individuality and control populations. There is a fine line between the individual’s choice and the societal pressures that indirectly force you to conform.

In contrast, in response to dressing as simply and uniformly as possible there are those on the other end of the spectrum who explore and represent their identity through clothing. Perhaps nowhere else is a better example of this than Harajuku, captured at its height by Shoichi Aoki’s publication Fruits in the early 2000s. Here instead of feeling overwhelming, the chaotic styles of Japanese youth seem to work symbiotically with all the colours and lights of the streets of Tokyo. There is a clear connection between the pedestrians and their environment, they belong there.

“Urahara”, short for ura-Harajuku (meaning “the hidden Harajuku”), has definitely changed in the last decade. Although there continues to be that same spirit with people mixing brands, reconstructing garments and so forth, there has also been the rise of the all-black, sharp silhouetted individuals. Perhaps like Simmel’s hypothesis on the business suit, the monochromatic style could be seen as a response to the loud Urahara styles of the 2000s. The presence of this style in the busy streets of Tokyo definitely adds a sense of balance. But when comparing it to the colourful, layered, repurposed fashions of Harajuku in the 2000s, it feels as though this change reflects a shift in the city away from individuality, instead towards conformity.

A parade of businessmen pacing through Tokyo in their suits.

Images of Urahara from ‘Fruits’, these images show just some of the diversity in this street-style culture.

On the other hand, the uniform could also be seen as an individual’s choice to shield themselves against overconsumption in a country that is the world’s third biggest clothes market. The everyday all-black uniform seems to require less upkeep and enables more rotation of clothing. Also over the last couple of years, “quiet luxury” has become a ‘buzzword’ in fashion and a point of much debate. The head-to-toe black styling, without logos or clashing patterns and colours feels as though it reflects this. As I write this in an office with majority monochromatic dressers their reasons centre around two key words, “efficiency” and “elegance”. It seems as though in this current climate more and more people only have the time to focus on these two words, but I hope there will always be those that keep the candle burning for the Urahara of the early 2000s.

Oh, and I know you have all been waiting to see the moccasins and cowboy hat icon, I managed to get a quick picture as he was stopped outside the station…