Coffee and Cabinets: London’s Hidden Arcade Scene

London is a city for niches; there is no shortage of musicians, gamers, artists, etc. who are hosting their own events and have active communities; however, they try to keep their activity under the radar, only for those “in the know”. This is particularly true of the London arcade scene, which makes an active effort to keep itself relatively unknown. Though it is hidden, if one looks, one can find a robust and diverse community, with people ranging from lifelong dancers to professional bodybuilders. They can find competitive fighters, cosplayers, hardcore punks, and more. This is what makes the London arcade scene one of the city's best-kept secrets. sabukaru sent me to tell the story of this scene, highlighting some of the most important places and talking to the most active people.

Trocadero Underground

The story of the London arcade scene truly starts with Trocadero Underground, a place that is hard to describe. It was a multi-story entertainment complex with arcades, movie theaters, indoor amusement park rides, restaurants, and even a Nickelodeon television studio. It is impossible to overstate the unique and futuristic atmosphere that Trocadero provided: one of the shops sold scuba diving equipment, it was home to some of the first-ever virtual reality games, and was also a common site for counterculture. It was connected to the Piccadilly Circus line which routinely had a Japanese breakdancing group, and many of the people who attended were a part of some subculture themselves, such as street dancing, punk, or gyaru.

The Trocadero was, at the time, the largest arcade in the entire world. In fact, it contained two multi-floor arcades, SegaWorld and Funland. SegaWorld was a 6-floor arcade that also had indoor amusement park rides, an AS-1 Simulator, a gyroscope ride, and family games like bowling and go-karts (which themselves even had their own unique twist, the go-karts having cannons attached and a target on top that kept score). The entrance was a shuttle elevator that took players up to the top floor which displayed a statue of Sonic spinning a globe.

Sonic statue, sourced from SegaWorld London Memorial

Funland was a 5-floor arcade but could also be described as a multimedia experience, as it had many immersive attractions, such as Alien War, a live reenactment of the Alien movie where the participants became fellow actors. It received much attention during its early days, even having a BBC documentary made for the attraction and having the starring actress, Sigourney Weaver, present on opening day.

Trocadero has many stories to tell; one report from Gabino Stergides states, during the release of Street Fighter II, that police had to control the massive crowds that came to play the game. When the game came out, there were lines 200 meters long waiting to play. The police, unaware a new game had come out, actually thought real street fights were breaking out at the arcade. Electrocoin, one of the distributors of Trocadero and owner of Funland, even made a parody flier “apologizing” for the police response to advertise the game.

Electrocoin Flier, sourced from game history academic Alan Meade

Unfortunately, the Trocadero arcades faced constant struggle. This was due to factors outside of its control, such as economic recession and Japanese companies like Sega and Konami withdrawing from the arcade market at the time. There was also general dissatisfaction among the intended audience; SegaWorld, for example, was advertised as a theme park and not as an arcade, which led to negative reviews, as the rides were seen as lackluster at best. SegaWorld attempted to relaunch, but it seems the damage had already been done. Due to leasing conditions, after SegaWorld’s lack of profit, it came under Funland, which itself closed after the electricity was shut down by the new owners. The closure of Trocadero could be said to be the start of the modern London arcade scene, as its closure led to the dispersion of the initial crowd and the creation of the arcades that exist today.

Las Vegas Arcade Soho

“The younger street kid in me, who was looking for an escape at the time, found the arcade when I needed it.”

Las Vegas Arcade Soho is “underground” in the literal sense of the word; initially a space for gambling (arcades in the UK have always been connected to gambling), a Japanese arcade resides in the basement. Located in central London and once described as “more Tokyo than Soho”, it is a space both for rhythm games and alternative fashion, cosplaying, and punk. The scene consists of people ranging from music producers to academics, and the fact that it is located in Soho, one of the most active parts of central London, only serves to highlight its underground (in the figurative sense) nature.

The basement contains a row of racing games, a pool table, a Museca and Pop’n Music cabinet, and a DDR and Pump It Up cabinet sitting next to each other. Pump It Up is the Korean counterpart of Dance Dance Revolution, having 5 pads instead of 4, one for the center, and the directional pads being placed on the diagonals.

Alisa Teterina

The Pump It Up scene is alive and well at the arcade, especially as viewed through the eyes of Alisa Teterina, a player who has been involved for over six years. Alisa has a background in dancing, and initially got into the game at a time when she was looking for a “second home”, a recurring theme among everyone I have interviewed.

Chatting with her, there is a palpable respect she has for the game and its players. She respects players for their skill and dedication and even stated that she considers them athletes. More importantly, she states that the arcade is a space where outcasts are accepted: it is ok to be into music, fashion, and video games that are not acceptable by mainstream standards. This is just as important as the games themselves and why she thinks the arcades must be kept alive.

Of course, because of this, the scene has a diverse cast of characters. Patrick, a competitive bodybuilder, Toby, the long-standing enthusiast, Alisa, for her part, being a “starving artist” who has made short films and does photography, this is the reason people come back.

As a game, Pump It Up is intense, to say the least. Pump It Up players do not stomp but instead rapidly tap their feet to the song (Alisa said that it is like tap dancing). There are many “infamous” songs, one being Paganini, based on the Italian composer Niccolo Paganini’s Caprice No. 24; it is seen as a testament of skill among players to competently pass this song.

I asked Alisa what she thinks is missing in the arcade and what she hopes to see in the future; she states that maintenance is a huge problem that owners may be reluctant to do for various reasons; she reminisces about “Las Vegas Wednesdays”, a time when regulars would come weekly, where she would get Chinese take-out with fellow players at 4 AM, and just wishes for the scene to grow.

Las Vegas Arcade Soho, photo sourced from Alisa Teterina

FreePlayCity

FreePlayCity is even more underground than Las Vegas Arcade Soho. It is an arcade in the Manor House district which doesn’t even have a sign outside of its front door (even saying it has a front door is debatable) and is next to a few closed buildings. Generally, people are lost when they come for the first time, and from experience, friends will genuinely question your intentions taking them to what looks like a random alley. Even people in the local area often don’t know the arcade exists.

However, it is by far the biggest arcade in London. When you enter, you can see the amount of space the arcade has; there are multiple sections, the first section is a row of early 2000s anime fighting games such as Personal 4 Arena Ultimax and BlazBlue. A bit further in, there is a space for some shooting games, such as House of the Dead: Scarlet Dawn, and some racing games, including a Crazy Taxi cabinet tucked away in a corner.

The rest of the first floor is dedicated to rhythm games; there is an entire hall of Japanese rhythm games that are not well-known to American audiences. For example, there is an Ongeki cabinet, a half-rhythm game, half-shoot ‘em up, which requires the player to play a song while also dodging bullets from enemies.

FreePlayCity also contains Chunithm, Sound Voltex, Museca Live, and many other rhythm games. There is a whole section of MaiMai machines, 2 DDR cabinets, a Pump It Up cabinet, and a DanceRush Stardom cabinet, a game like DDR but with an open panel and a sensor that can track the player’s entire body to allow for more fluid gameplay and more expressive movement.

The second floor of FreePlayCity is dedicated to fighting games; they run on old Astro City cabinets with CRTs and are hooked up so that 2 players can play without using the same cabinet (the cabinets are set up opposite each other). The arcade has Street Fighter III: Alpha, 3rd Strike, Tekken II, and some other games such as Marvel vs. Capcom though it is currently broken (the rest of the second floor is where broken cabinets reside).

Astro City cabinets, photo sourced from Alisa Teterina

FreePlayCity has a lively community; there are weekly fighting game community events hosted by Jin, many professional players come on a weekly basis, and there are occasional rhythm game tournaments as well, though they are not as active. There is a discord server for the community, and rhythm game players often use it to share their high scores, songs they did perfectly, videos of them dancing, etc. The community is tightly knit and also has an alternative aesthetic; walking into the arcade, you can see many people into gothic fashion, cosplaying, and so on. It provides a unique atmosphere that keeps people coming back.

Photo sourced from Alisa Teterina

The Community

I had a chance to talk to Toby Na Nakhorn, a veteran of the London arcade scene who has hosted the biggest dancing game tournaments in London. In the early 2000s, Toby danced himself, and you can find footage of him attending cyphers and battles. He is interested in hip-hop dance (specifically tutting, pop-locking, and b-boying), and he incorporates elements from these dance styles into his gameplay.

Toby had many tales to tell of his time in the arcade scene; the most striking was a story of his friend who had his back slashed with a samurai sword by Chinese gangsters. He said that, at the time, there was some gang-related activity going on near a few arcades on Tottenham Court Road, and some of them were even avid players themselves. Apparently, his friend was mistaken for a rival gang member, and so he was attacked. As Toby says, “Anything goes in the arcade”.

Of course, there is much more positive to say than negative. Toby started by running Pump It Up Tournaments in the early 2000s and continued until 2023. His last tournament was a Pump It Up tournament in 2023 at Babylon Park, which actually was the largest Pump It Up tournament in London.

Babylon Park Pump It Up tournament, photo sourced from Patrick Claudino

Toby states that it actually used to be common for dancing game players to have dancing backgrounds; even in the early days of DDR, many players “freestyled”, caring more about expression than doing well at the game. As time progressed, people started to play for score, and so they focused on more technical gameplay.

I did talk to Toby about the state of the arcade scene and its community, where he seems to show some remorse; he states that it is hard to keep arcades alive, and on some level, this is because of the owners themselves, which he sees as out of touch. He says that many arcade owners are stuck in the past, are not open to new games, and do not care about fostering a community within their arcade. Once, when he suggested adding music games to an arcade, the owner stated, “We don’t want those kinds of people coming to our arcade.” It seems that the stereotypes of arcade gamers even penetrate the arcade itself.

Still, he has passion for the scene and regularly attends tournaments, runs social media for many of the London arcades, attempts to fix cabinets, and does his best to keep the scene alive. It is because of people like him that it continues to thrive.

Legale Issues

One thing that was interesting talking to Toby about was the legal status of the arcades; of course, running an arcade in and of itself is completely legal, but there are some particular games that constitute legal gray areas.

For instance, old school shoot 'em up cabinets are expensive, are no longer being produced, and are valuable collector's items. Cave shmups like Dodonpachi and Mushihimesama can often go for over $5000 just for the game itself, let alone the actual cabinet and controller. Because of this, some opt for emulation, as it is a cheaper and more accessible way to play these games. However, depending on the country, even owning the original motherboard does not necessarily give an arcade owner the right to emulate the game.

In the past, certain arcades went to great lengths to avoid legal trouble; some even used to keep certain games in a separate room only for those “in the know”, which was inaccessible to the public. This is no longer done today, but there are still some gray areas when it comes to licensing and distribution.

This does pose a difficulty for keeping the arcade scene alive, as there is a genuine hesitation to streaming. Even though the London arcades do have the rights to the cabinets they own, it seems there’s still a historical remnant of this attitude.

Fighting Games

In addition to the rhythm game community, there is also an active fighting game community. I was able to talk to two members, Zak, who is responsible for many fighting game tournaments across London, and Jin, who hosts weekly community nights at the arcade.

Zak, photo sourced from Alisa Teterina

Zak shows a clear passion for the scene and the games he plays. He has been involved since the days of Trocadero, where he was introduced to fighting games through a friend and loves anime fighters such as BlazBlue: Central Fiction and Melty Blood for their unique art styles and diverse cast of characters. Having a background in art himself (being involved in dancing and drama in his early days), he started working in the arcade industry as a way to combine his interests with something he felt he could use to progress forward.

Zak hosts tournaments with an organization called Nth Gen Media, which continues to put on events despite many struggles, such as once having to move 200-pound cabinets halfway during a tournament. He states that the community has a DIY ethos and that you just have to make things work, as “nobody owes you any favors”. However, he does mention that the community is willing to help out when necessary, for instance by participants bringing PS1 consoles to an event because his team did not have enough.

Being a self-described “old head” in the scene, he reminisces about the days of Trocadero and says that though there are many arcades in London, they are in awkward places which makes it harder for people to come and stay active. Still, he appreciates the scene for what it is today, does what he can, and loves it for its ability to bring in unique people (something which I have learned firsthand).

Jin, on the other hand, is a newer player who came to the scene around 2012 when Las Vegas Arcade Soho was at its height. He has been in multiple bands, has a background in game development, and runs weekly Tekken nights at FreePlayCity.

Jin has a unique perspective on fighting games; to him, fighting games are like playing an instrument, where you learn the moves (the “notes”) of a character and then can express yourself creatively (though he thinks personal expression is being squashed by modern game design). Showing some slight sadistic tendencies, he says part of the appeal of fighting games is that “there’s always a victim”.

In the same way Zak reminisces about Trocadero, Jin reminisces about the old days of Las Vegas Arcade Soho; in the early 2010s, it had much more activity, and was a similar cultural hotspot. Back then, it was a common social space for different subcultures and was a spot that even non-gamers frequented just to sit down and eat their food.

Jin says that FreePlayCity offers something that nowhere else does, which is proven by the time he had someone’s dentures end up on the front table while he was working. He has a more optimistic perspective, as he is the only person to say “nothing” when asked what was missing from the scene (he said explicitly, “Even after the console era and even after the pandemic, we are still here”). Jin has hopes to make a video game based off of BeyBlade and would like to see a major fighting game tournament in London.

Chief Coffee

To end, Chief Coffee is another arcade with an interesting story; it is a cafe with a Japanese arcade and a pinball lounge on separate floors. Located in Turnham Green, it has a similar hidden status, as it is not on the main strip and also is hidden in another alley. As a matter of fact, it is so out of the way that there is a sign guiding newcomers which is easy to miss.

Photo of sign, taken by author

The cafe has a relaxing atmosphere with board games, books, and background music. People can enjoy a cup of coffee, a pastry, do work, or just chat with a friend. Throughout the cafe, there are various trinkets from different franchises; behind the baristas, there are figurines from Ghostbusters, Kirby, and Taiko no Tatsujin. There is also a Space Invaders alien on the glass and a couple of posters from when the arcade first opened.

Taiko no Tatsujin figurines, photo taken by author

The second floor contains the arcade. It has cabinets for Chunithm, Nostalgia, Maimai, Taiko no Tatsujin, and Groove Coaster, a game where the character rides on a course that takes twists and turns as they play different notes. There are also some racing games, including an arcade-exclusive version of Mario Kart and Scotto, a game that is like an arcade version of beer pong.

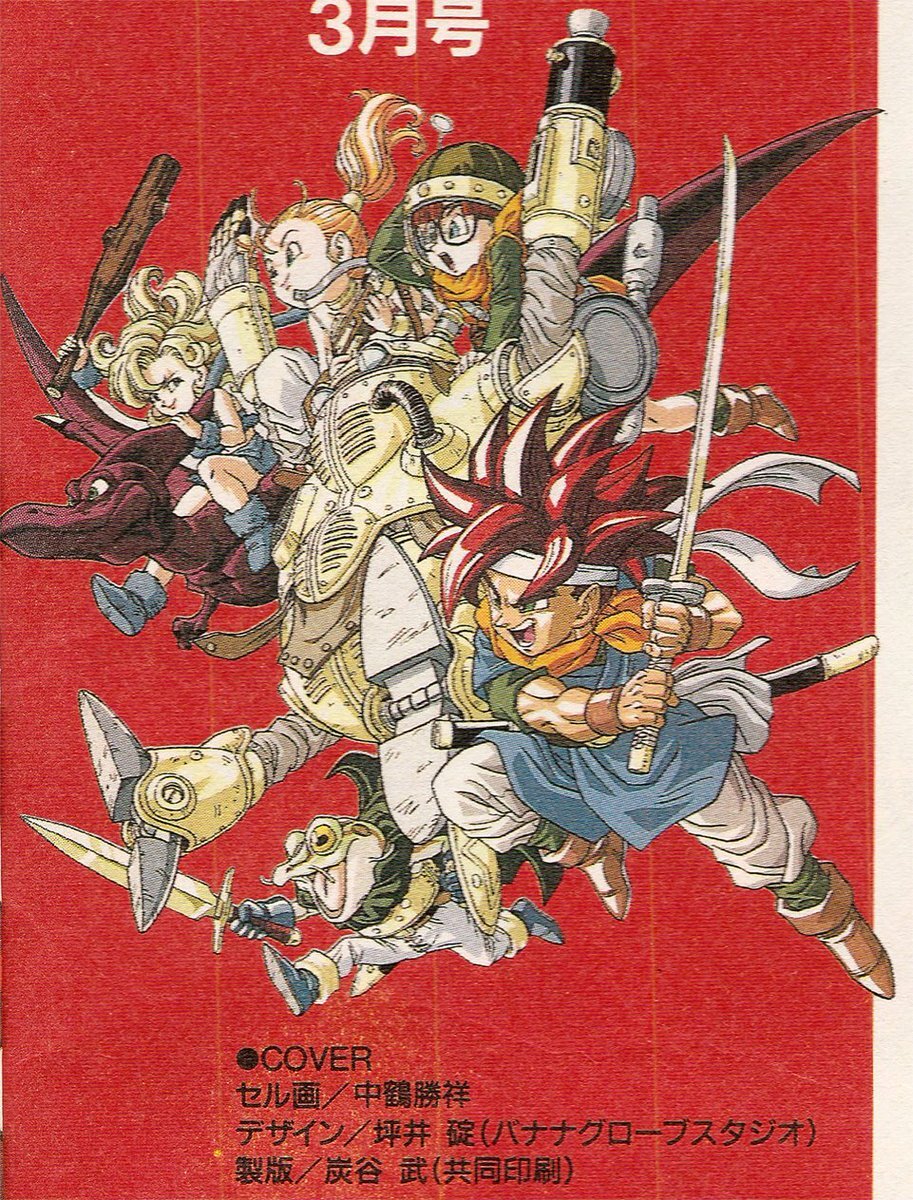

The walls of the arcade room are filled with different posters, from BlazBlue to Street Fighter. There is a set of stairs that leads to an exit, and on the railing, there are stickers from different video game and anime franchises. One interesting poster is an old Neo Geo banner with G-Mantle (the mascot for SNK) and the phrase “Bring the cool games over here” in Japanese.

SNK Poster, photo taken by author

The ground floor contains a pinball lounge with themes ranging from Guardians of the Galaxy to Stranger Things and Godzilla. There is also a powerbox with different stickers and some skateboards hanging on the wall. There have been pinball tournaments in the past, the last one being in 2019, paying almost $2000 collectively to the top players.

conclusion

The London arcade scene is alive and well. It has a dedicated base of players who come because of their enthusiasm for the games they play and attempt to master. There are a variety of different communities, from the rhythm game community to the fighting game and even the racing game community (something which is currently experiencing a resurgence though there is not enough space to discuss this in detail).

Throughout all the interviews, there were some common threads. People do seem to have conflicted feelings, where on the one hand, they show nostalgia for the past, but on the other, they highlight the amount of events, spaces, and activity that exists today (maybe they themselves do not even notice this conflict, living within it for so long). Though games are what bring people there to begin with, they all stay because of the community they found which in their eyes is like no other. They all wish to see the scene grow, wanting more maintenance, tournaments, and events, and everyone does what they can to make this a reality.

The scene is underground by nature. It is kept underground due to the community’s desire to keep itself as a community and as an attempt to not commercialize the arcades that still exist (a trend that everyone interviewed showed concern for). This dynamic does create a more dedicated base, though it also makes expansion more difficult.

There were many arcades that couldn’t be covered just due to space or not being able to contact the owners/players. Of notable mention is Heart of Gaming in Croydon which took many of the Trocadero machines and was described by one member as “FreePlayCity but everyday”. Unfortunately, I could not get in contact with the owner.

Still, the fact that, aside from all the places covered, there is still more to be said is a testament to the state of the arcade scene today. From the early days of the Trocadero to the Las Vegas Arcade Soho, FreePlayCity, and Chief Coffee, there are a plethora of venues keeping arcade games alive. One can find the scene so long as they look hard enough. It is “best kept secret”, in both senses of the term.

words by Julian Jefko