Hideo Kojima: Making the Impossible Possible

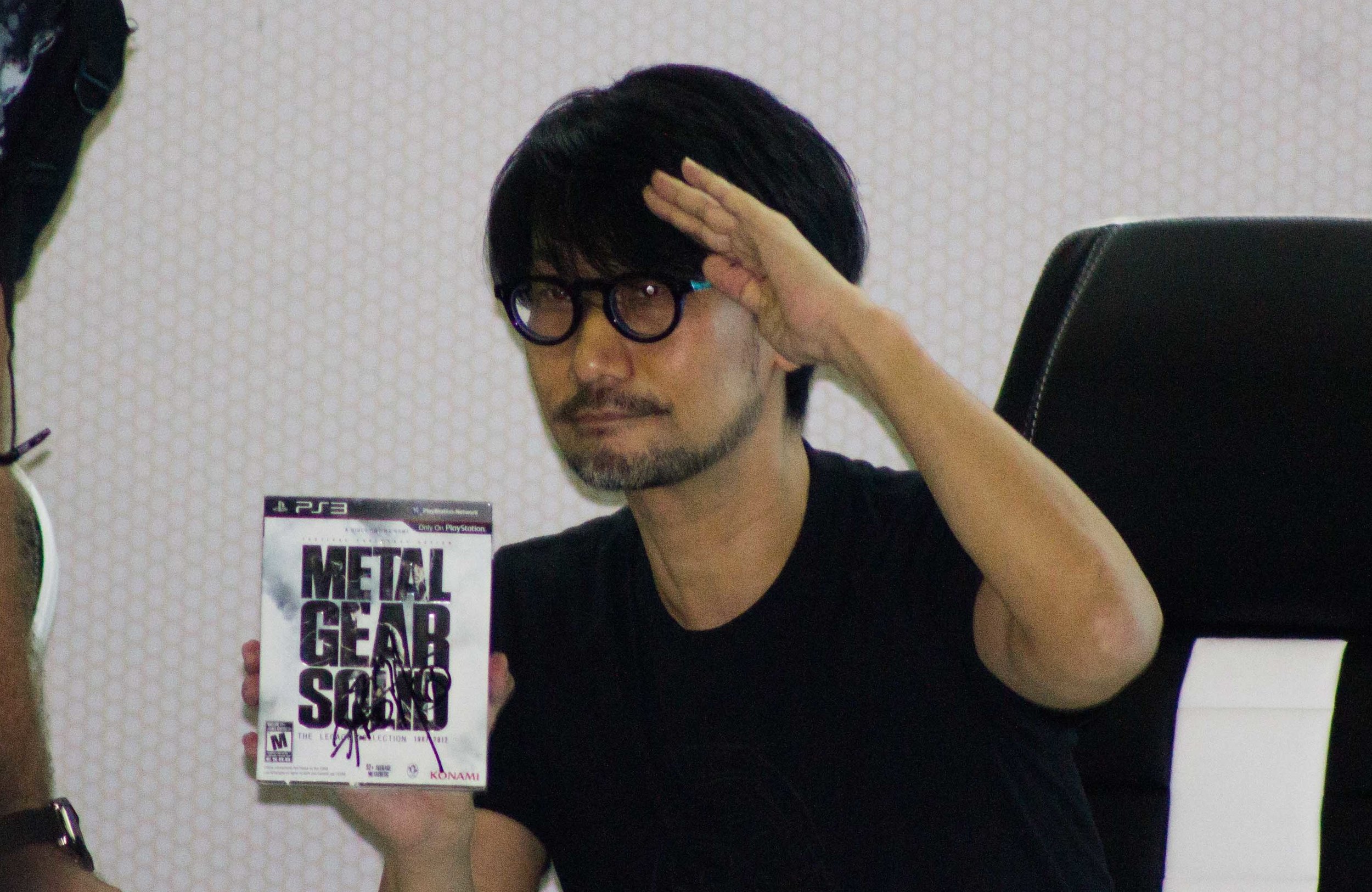

Hideo Kojima

A name synonymous with video games, Hideo Kojima is the father of the stealth genre. Known for breaking the conventions of traditional game design, and establishing innovative design heuristics, his games have pushed hardware limitations to the extreme, utilising cinematic properties to create unique interactive experiences. He is perhaps the only AAA video game auteur, a term which stems from the auteur film theory in which directors are the central impetus for the creation of a movie.

Derived from the French word for “author,” the theory states that a film’s style, content and use of filmmaking techniques are essential in distinguishing the director’s personality, and when used recurrently throughout a body of work, become their signatures. According to American film critic, Andrew Sarris, who coined the theory in 1962, “over a group of films, a director must exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style, which serve as his signature. The way a film looks and moves should have some relationship to the way a director thinks and feels” [Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962].

Directors such as Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and Lynne Ramsay can be considered auteurs of cinema, with each utilising particular cinematic devices that have become synonymous with their work. Spielberg's use of dolly zooms to close-ups to convey the reaction of a character, whether to a giant shark or an alien invasion, has become one of his directorial trademarks. So tethered to his work, the technique has even been described by video essayist, Kevin B. Lee as the “Spielberg Face.”

Likewise, Scorsese's use of pop songs in his films not only revolutionised the way popular music was used in studio films but has become one of his signature cinematic devices. His use of The Rolling Stone’s “Gimme Shelter” in Goodfellas [1990], and the opening of The Departed [2006], amplifies each film’s topics of war, drugs and murder by way of a song with subjects similar while also showing the director’s reverence for the band. This was later proven when Scorsese directed The Rolling Stone’s documentary, Shine a Light, in 2008.

In Ramsay’s cinema, her auteurism shines through her decision to present young characters in dark and terrible circumstances. From her debut feature, Ratcatcher [1999], through to You Were Never Really Here [2017], Ramsay’s portrayel of mature subjects [extreme violence, death, and poverty] from the perspective of young and underdeveloped minds, exposes her disposition as a storyteller. Children, in Ramsay’s films, are used to frame the world through an unfiltered, unbiased perspective which, as stated by The Saturday Auteur, “provides unflinching reflections of human nature that form the centrepiece of her work” [2020].

While historically used to describe film directors, the rapid growth in video game production has led to a plethora of games with similar authorial influence. Indie developers such as Edmund McMillen [The Binding of Isaac, Super Meat Boy] and Jeppe Carlsen [Limbo, Inside] are known for implementing personal motifs such as religious themes or coming-of-age trauma in their games. These recurrent motifs can be considered aspects of auteurism, presenting elements of the director’s personality, and their moral viewpoints through the game’s aesthetic and storytelling.

The independent, low-budget nature of these games allows the director, or lead designer, to enjoy a substantial degree of authorial freedom, with risks taken in content and style regardless of profitability. Indie games are cheap to make, and in turn, their teams are privileged with much more creative liberty than franchise games such as Call of Duty or Assassins Creed. In the current AAA market, game developers are not so privileged. Due to the high costs, mega publishers such as EA and Ubisoft are required to appease the largest audience possible in order to recuperate finance. Therefore, the idea of a game solely curated to adhere to one person’s personality, as per auteur theory, is by definition a risk; difficult to market, and unlikely to appease the millions of customers to which the publisher is required to sell. This is why every Call of Duty game looks and feels the same.

In AAA gaming, auteurs are simply hard to come by. One person’s vision, no matter how artistic or game-changing, does not necessarily equal profit. Kojima, however, has been working in the AAA market since he first entered the world of video games, and despite the millions of dollars invested in his titles, has maintained his mantle of video game auteur.

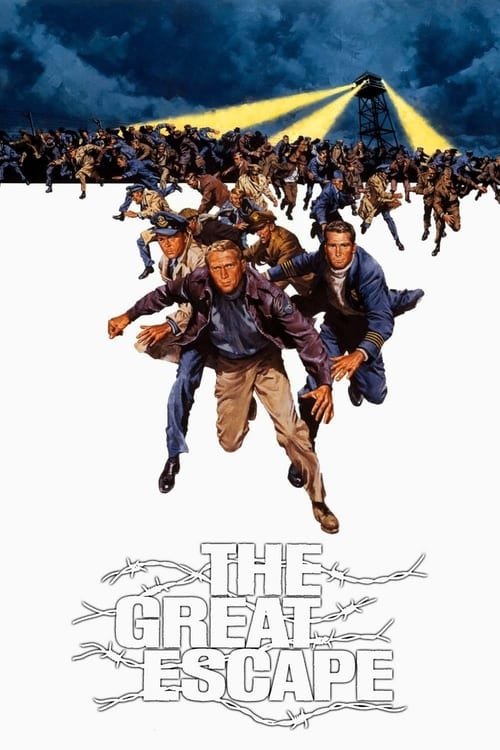

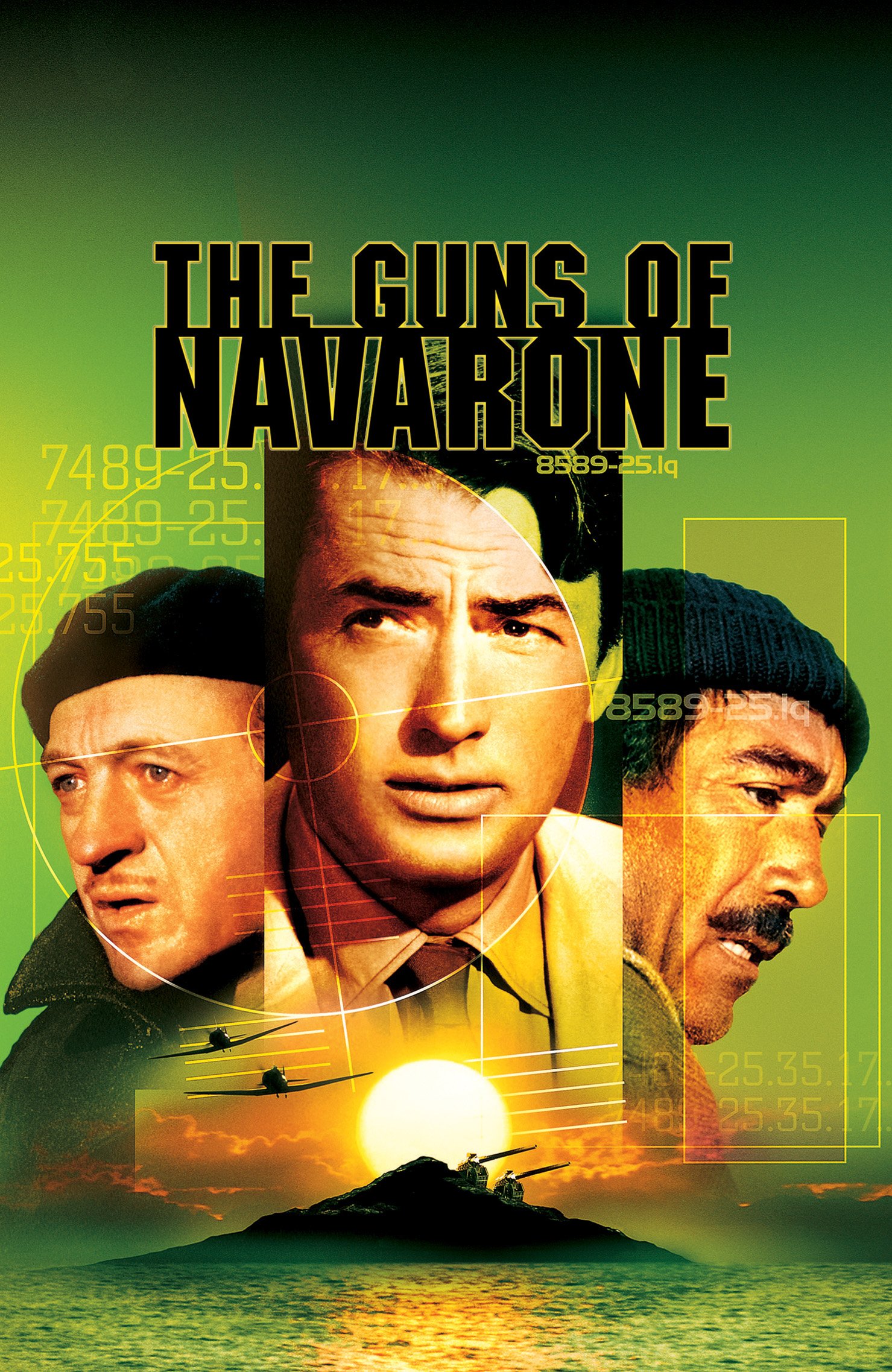

Born August 24, 1963, in Setagaya, Tokyo, and later moving to Osaka, Kojima was brought up watching movies with his parents. His father, Kingo, was a staunch cinephile, with a strict rule to always finish a film in one sitting. He introduced Kojima to the world of Western cinema. Two of their favourite films included The Great Escape [1963], and The Guns of Navarone [1961] – American war movies which would inspire Kojima to no end.

“70% of my body is made of movies,” insists Kojima, in his Twitter bio, spending much of his school years making films with his friends. Intent on pursuing a career as a filmmaker, Kojima’s dreams were cut short when his father died when Kojima was just thirteen years old. As a result, money became tight, and Kojima opted instead to pursue a more stable career path: studying economics at university. His uncle was a struggling artist, and Kojima didn’t want to fall into the same precarious career path. However, when exposed to Shigeru Miyamoto’s Super Mario Bros. in 1985, shortly before he graduated, he saw a new avenue for telling stories through interactive experiences. He saw game design as a second chance to achieve his storytelling aspirations.

In a Rolling Stone essay in 2017, Kojima states that he considered early video games, Pong, Speed Racer and Space Invaders, as novel ways to “foster emotional investment” through competition and simplistic controls. But they lacked story. With Super Mario Bros., that emotional investment skyrocketed with the inclusion of a simple narrative and character design, controlling Mario with “only two actions, jump and run,” to save the princess.

The evolution of video games meant that stories could be simplistic, interactive and cinematic. Inspired by Yuji Horii’s The Portopia Serial Murder Case ,a visual novel boasting a complex narrative and multiple endings, and encouraged by his mother to follow his dreams no matter what, Kojima decided to pursue a career in video games, joining the video game giant, Konami, in 1986.

Rough Start at Konami

Initially disappointed with his role at Konami, Kojima felt restricted by the company’s design focus. In an interview with video game magazine, Retro Gamer, in 2007, Kojima explained that he joined Konami to create games for the Nintendo Entertainment System, otherwise known as the Famicom in Japan, but was instead lumped with the MSX, Microsoft and ASCII’s inferior home computer system. With a meagre 16 colours compared to the Famicom’s impressive 56, when limited to the MSX, Kojima began to wonder “how on earth [he] could make games with that” [Retro Gamer, Issue 35, page 74, 2007].

Kojima wasn’t the only one to question Konami’s decisions. Many of his co-workers were baffled by his hiring at the company. He had no experience in video games and was assigned the role of “planner,” a title shared by no one else in the company. In an interview for American network, G4’s Icon series in 2004, Kojima lamented that “Back then it wasn’t easy for me to fit into a group. People sort of accused and attacked me as being this guy who didn’t have any technological skills.”

Regardless, Kojima’s first project, Penguin Adventure [1986], in which he was an Assistant Director, was considered one of the best action titles on the MSX. A sequel to 1983’s Antarctic Adventure, with a greater variety of stages, more bosses, and RPG elements such as purchasable items and mini-games, the project proved that Kojima had a uniquely expressive vision, his experience notwithstanding. The game even included multiple endings such as the secret good ending if the player pauses the game enough times.

Due to his success on Penguin Adventure, Konami hired Kojima to work on what was to be his directorial debut, a game called Lost World, supposedly set on the Titanic. After working on the title for six months, the game was unfortunately cancelled, further adding fuel to his co-worker's discontent. Yet, despite the cancellation, Konami recognised Kojima’s ability to work effectively within MSX’s hardware limitations and promptly brought him on to lead the team for one of the company’s struggling assets.

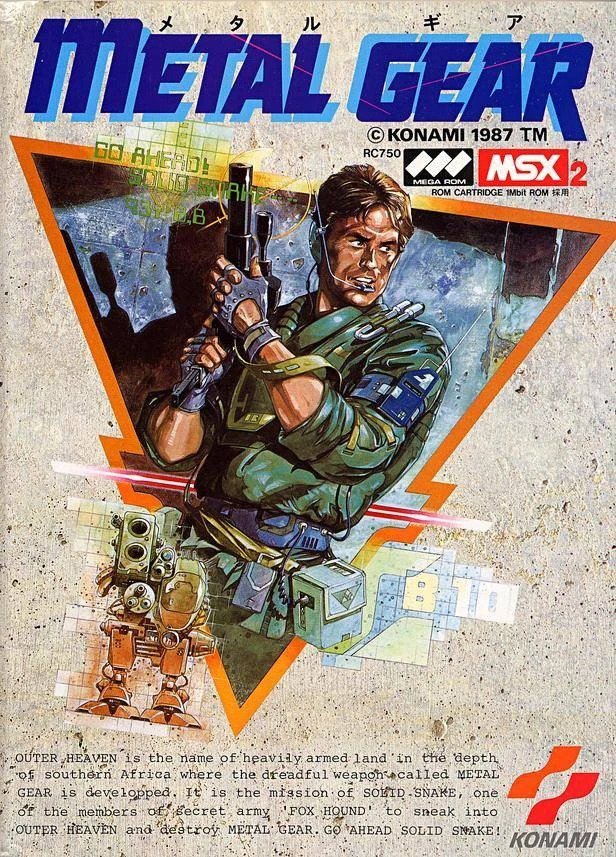

Metal GeaR

Originally conceived as an all-out, action-oriented war game, Metal Gear was a trouble child at first. Konami wanted Kojima to develop a game like Capcom’s Commando, but for the MSX2. Only, the console wasn’t powerful enough. Hardware limitations made it impossible to show many character sprites on the screen at once, making it impossible to assimilate the gung-ho, run-and-gun shooter, the higher ups at Konami desired.

The pressure was on. Kojima still had not managed to direct a game to completion, and many of his co-workers were starting to notice. “I was the only one in the company who had never had any of his games released,” Kojima explained to G4, “and people, instead of saying hi, would come and say, ‘at least complete one game before you die’.” Little did Kojima’s co-workers know that his creative ingenuity would not only solve the problems of the MSX2’s limitations but would establish one of the most successful video game franchises of all time.

When Kojima began work on Metal Gear, he had two thoughts: How could he make this game cinematic? And how could he make it work on the MSX2? Inspired by his favourite war films – The Great Escape and The Guns of Navarro – he set to work redesigning the game, pulling focus away from action-oriented gameplay and creating a core loop designed around stealth and evasion. Establishing novel design heuristics such as enemy range of sight, and dynamic AI that shifted when players were spotted, Kojima realised the game’s evasion aspect, with protagonist Solid Snake infiltrating a mercenary base, avoiding enemies, in search of a newly developed nuclear weapon.

Taking notes from John Carpenter’s Escape from New York [1981] and James Cameron’s The Terminator [1984], with Metal Gear, Kojima created something entirely new. Instead of trying to reproduce Commando, he developed the stealth mechanics pioneered by Castle Wolfenstein in 1981 and helped establish the stealth genre of video games.

Making the Impossible Possible

Kojima’s decision to turn Metal Gear from a Commando-esque shooter into a tactical, evasion-first espionage game, helped establish his core design sensibilities: to make the impossible possible.

During his keynote speech at the Game Developers Conference [GDC] in 2009, Kojima described his design theory as analysing the “barriers of impossibility,” such as hardware and technology limitations, and working out ways to overcome them. According to Kojima, in game design, everything that has come before is seen as possible, and everything that hasn’t been done yet - impossible. Yet, “Impossible is merely an assumption,” and “making the impossible possible [simply] demands preconceived notions be discarded” [Kojima, 2009].

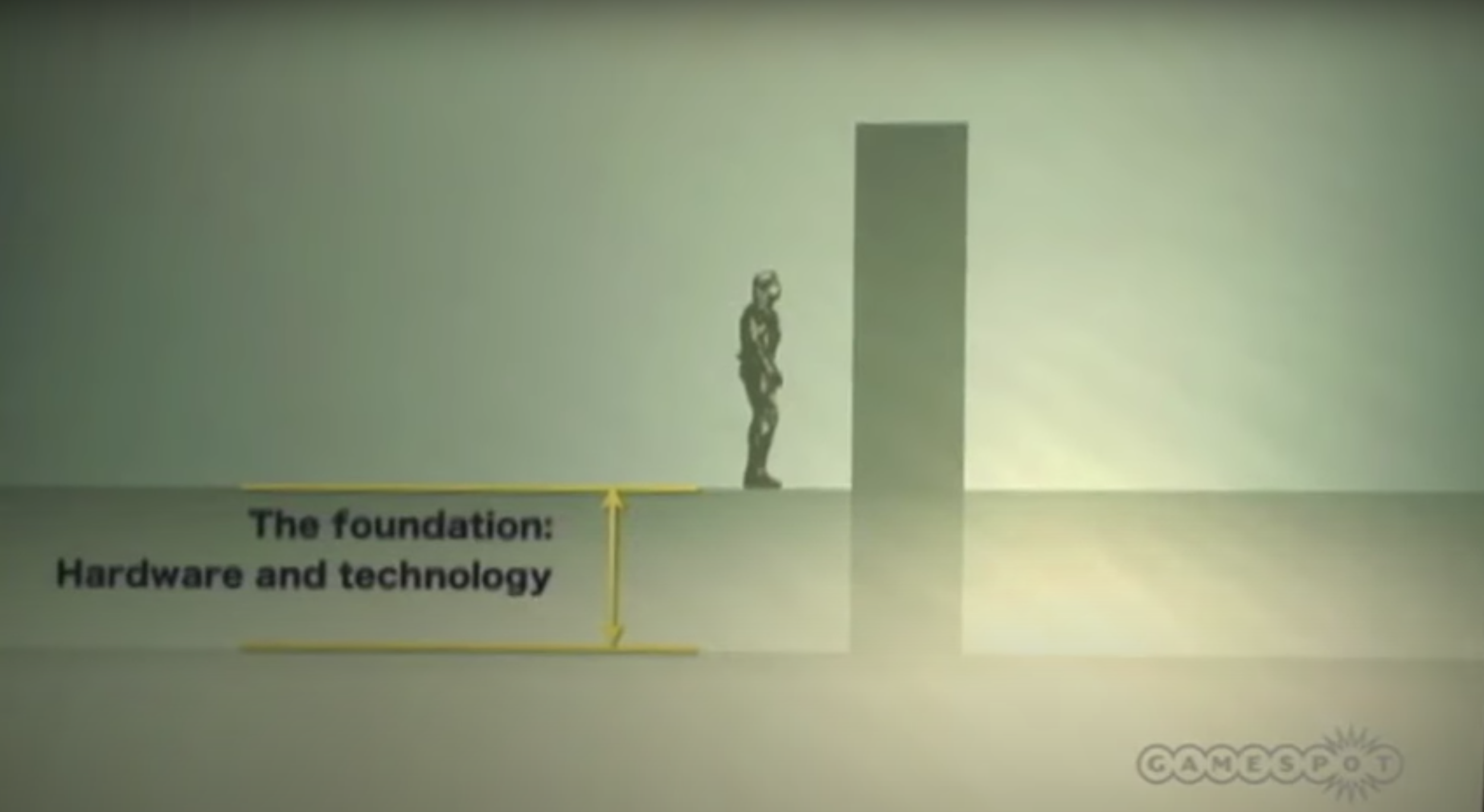

To further illustrate this theory, Kojima presented a cartoon Solid Snake trying to scale a metaphorical “wall of impossibility,” unable to jump over it as Mario would in Super Mario Bros.. Instead, Snake opts to either pole vault, fly or blow up the wall. Thereby, scaling the wall through creative [and explosive] ingenuity.

Kojima suggests that video games are a technology-dependent media, the foundation of which “rises depending on the hardware and technology.” Using a metaphorical “floor” to exemplify this “foundation” during his presentation, rising along with technological innovations, Kojima shows the cartoon Snake coming close to overcoming the wall of impossibility.

Yet, technology is only half the battle, there will always be limitations. It is within the game’s design that the wall of impossibility is fully scaled. Despite the rising floor of hardware technology, Snake still can’t get over the wall. So, Kojima animates a cartoon ladder which he labels “game design.” Within the context of Metal Gear, this ladder represents stealth.

When Kojima was brought on to do Metal Gear, Konami wanted a war game, but the MSX2s hardware wasn’t up to scratch. So, what did he do? He analysed the limitations of the hardware, how the console couldn’t handle many sprites on screen at the same time, and decided to take them out leaving Snake with only one or two enemies on screen at a time.

To make this satisfying for the player, he changed the focus to avoiding combat rather than seeking it out, maintaining player engagement by creating competition through infiltration. By shifting design priorities to accommodate the MSX2’s hardware limitations, Kojima overcame the wall of impossibility and, in doing so, created a new way to play.

A New Way to Play

Another way in which Metal Gear stands out amid the humdrum of AAA action titles, is through the series’ inherent pacifism, presenting themes of anti-war, anti-nuclear weapons, and anti-violence. In Metal Gear, evasion and infiltration are the primary methods to completing each game, violence is a last resort. In line with the game's design sensibilities, the series is about avoiding conflict at all costs.

In his essay for Rolling Stone, Kojima equates his game design sensibilities to Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk: a war movie where the focus is on escaping conflict, rather than to face it. Like The Great Escape, Kojima writes, Dunkirk “portrays a mass allied escape,” in which “killing your enemies with guns is not the answer. Escape is a form of resistance... It is an anti-war movie.”

Like Dunkirk and The Great Escape, Metal Gear is about prioritising stealth over combat and using infiltration and espionage to fight back against military factions. It is an anti-war series, challenging the player to seek out weapons of mass destruction, such as the titular, nuclear, Metal Gear robot, often the final boss in each game, and destroy them.

Kojima suggests that in video games, conflict is a key component. In Pong, Speed Race and Space Invaders, players are pitted against each other [or computers] to achieve a high score. In Call of Duty, the narrative often revolves around real-world warzones, taking down your enemies with guns and bombs, and if you’re playing online, competing with other players to rise up the ranks. Doom [2016] and Bloodborne [2015] are just two of many games that incentivise violence through gameplay; encouraging players to fight in order to obtain health points, or just to see a bloody execution with a chainsaw. In each of these games, conflict is a means to victory. Kojima points specifically to Super Mario Bros., in which the priority is to fight Goombas, Koopas and eventually Bowser to save the kingdom: “A detailed explanation isn’t required. All Mario needs to do is rescue the princess and defeat his foes.”

Metal Gear is different. Metal Gear is about avoiding conflict at all costs. By placing emphasis on evasion, Metal Gear becomes a series about preventing violence and, in turn, nuclear war. This couldn’t be more illustrated than in the later title Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater [2004] in which Kojima wished to instill an anti-war, anti-nuclear weapons message, educating players about the consequences of building nuclear weapons.

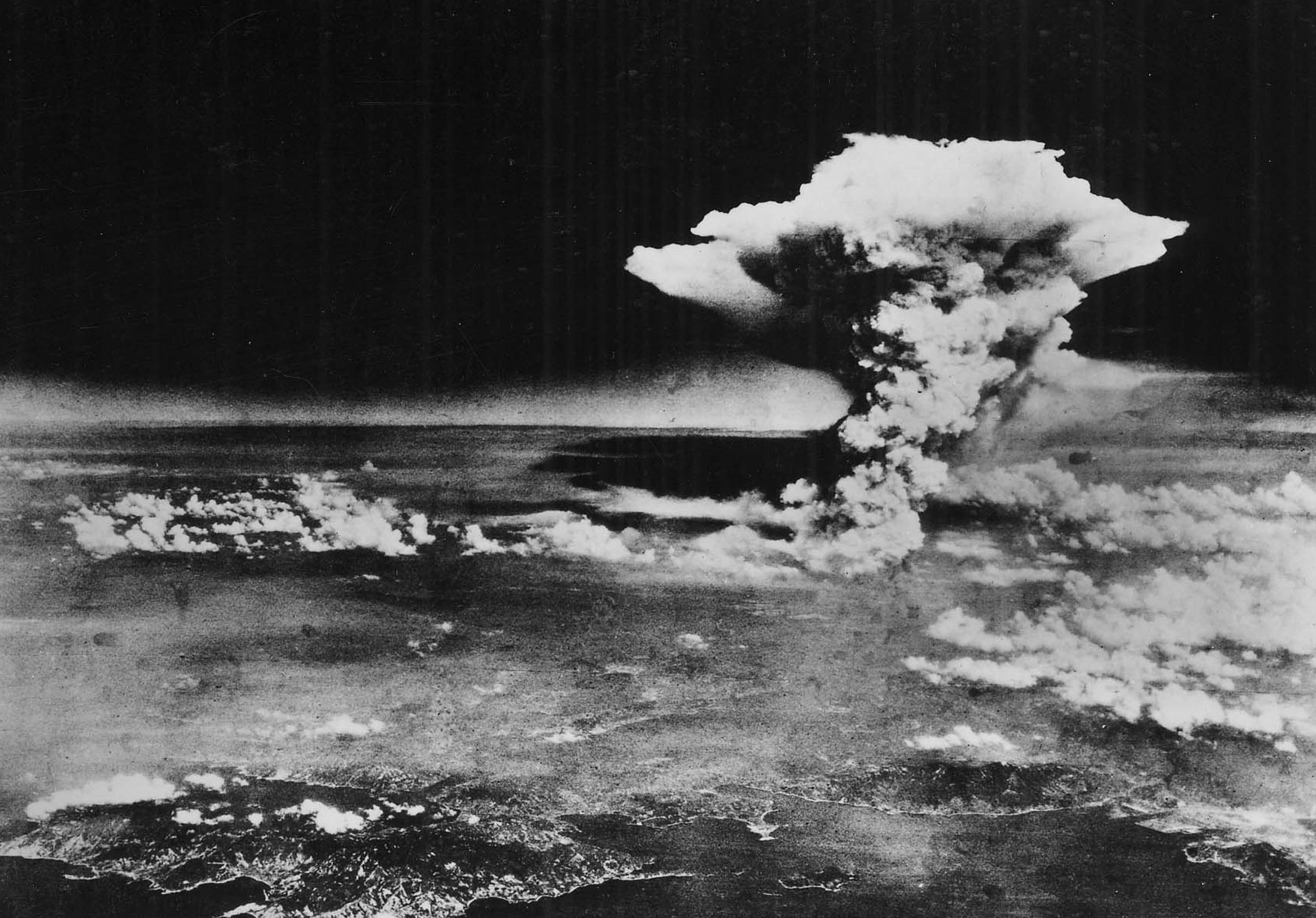

Set in 1961, three decades before the original Metal Gear, with MGS3, Kojima felt that he needed to educate younger generations about the Cold War, “What caused the U.S. and the Soviet Union, allied in WWII to become enemies and build nuclear arsenals against one another?” He wanted to explore the complexities of human conflict, how there are always two sides to war, the nature of good versus evil and how “There is no such thing as absolute justice or corruption.” The son of a generation of Japanese who witnessed first-hand the effects of nuclear weapons during World War Two, and consequently turned the nation away from warfare ever since, Kojima felt he needed to imbue his games with the same sense of anti-war, anti-nuclear weapons.

Kojima continued this pacifist approach in Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain [2015], which contains a mission to rid the world of nuclear weapons. Designed to instill the idea that once one country owns nuclear weapons, all countries will endeavour to hold them to ensure leverage in international warfare Kojima wanted players to truly “understand what it really means to take a stand against war and nuclear weapons.”

Kojima sees video games as a method of telling stories that engage players emotionally, through interaction, and educate them about history, humanity, and the consequences of violence and warfare. He approaches narrative the same way he approaches game design, prioritising anti-conflict to circumvent hardware limitations and provide non-violent ways to compete. His goal is to create a game which values human connection over conflict.

“Video games are a natural fit for “fighting” and “competition,” but even so I felt that they should be able to promote an anti-war, anti-nuclear weapons message, and more so, it was necessary. I also wanted to change the idea that games could only be about fighting” [Kojima, Rolling Stone, 2017]

According to Kojima, ever since the release of the first video game, Spacewar!, in 1962, which pits two player-controlled spaceships, “the needle” and “the wedge,” in a dogfight in space, video games have been about competition through conflict.

Referencing Nawa, or “The Rope” [1960], a short story by Japanese author, Kōbō Abe, to further illustrate his thesis, Kojima explains that humanity’s oldest tools are the stick and the rope. The stick to hit back what is evil, and the rope to bring in what is good. Since the dawn of video games, players have been using metaphorical sticks to fight and compete. For his most recent game, Death Stranding, Kojima decided to change this.

“It's time for humankind to take the rope in hand. We are ready for a game not based on competition, but on the rope that will bring good to the player and make connections. We don't need a game about dividing players between winners and losers, but about creating connections at a different level” [Kojima, Rolling Stone, 2017].

The Death of Metal Gear

In 2014, Konami released a demo for a new title directed by Kojima. P.T.. An enigmatic, nightmarish “playable teaser” for a Silent Hills revamp starring zombie-hunter supreme, Norman Reedus, and co-directed by monster movie legend, Guillermo Del Toro. More about Kojima’s teased turn on the classic horror video game series here in Carina Scherpenisse & Joe Goodwin’s intricate dissection of Kojima and his cinematic inclinations.

However, despite the excitement garnered by P.T., which achieved over a million downloads from the PlayStation Store, and the immense success of MGS5, selling over 6 million copies in its first year, relations between Kojima and Konami were not so jovial.

At the time of MGS5’s announcement in 2012, Konami was in a state of flux. No longer were story-driven, AAA, “traditional” console games their main source of income, with mobile games such as Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Links and Pro Yakyū Spirits bringing in the big bucks. The proliferation of smartphones had brought gaming to the masses, encouraging even the most casual player to sink hours into collecting digital cards or simulating their favourite sports at the touch of a screen.

Konami was suffering the industry-wide market shift towards mobile gaming, plagued by diminishing returns on many of their biggest console titles. AAA games had become so expensive, and so time-consuming that even their biggest releases were becoming financially unviable. In returning to auteur theory, risks in content and style were becoming unprofitable, and thereby unfavourable to investors. Why risk an artistic experimental game that might spend a decade in development, and cost a mountain of money, when the alternative, copy and pasting mechanics, worlds and game design, is so much more likely to reign in a profit?

As a result, strict budgets and even stricter deadlines were placed on the development of MGS5 and Silent Hills, with their respective teams [each led by Kojima] pressured to stick to these constraints via severe micromanagement and a controlling logging system. Konami installed surveillance cameras in their offices to ensure that staff were putting in the maximum effort, and Kokatu reports that even employee snack breaks were logged internally. This led to the rushed release and eventual splitting up of MGS5 into two parts: Ground Zeroes, a glorified demo for the full game, The Phantom Pain.

As expected, this didn’t mesh well with Kojima, who had championed creativity and innovation in his approach to game design, always pushing to make the games he wanted to make, regardless of profitability or deadlines. Things hit a boiling point when Hideki Hayakawa, producer of the hugely popular mobile game Dragon Collection, began to rise up in the company’s ranks, insisting that mobile games were the future of Konami’s video game output.

Hayakawa quickly gathered influence, and eventually became the President of Konami Digital Entertainment in 2015, putting his mobile game strategy into full swing. Kojima, out of patience with the company’s lack of employee consideration, and done with deadlines and budgets, decided to leave the company in the same year, regrettably putting an end to eagerly anticipated Silent Hills and any future Metal Gear games directed by him.

The Birth of Death Stranding

In 2015, Kojima took his studio, Kojima Productions, independent, leaving him and his long-time collaborators, Yoji Shinkawa and Kenichiro Imaizumi, with some pressing issues. Not only did they have to form a new development team without Konami’s backing, but they had to navigate the complex logistics of organising a new company. So, how did they do this? Well, fortunately for Kojima, through years of collaboration, he had formed an effective relationship with Sony, the Japanese media giant who had been a constant publisher of his work ever since Metal Gear Solid in 1998. Sony was quick to swipe up the unanchored Kojima, establishing a partnership for him to develop games exclusively through their consoles.

In 2015, Kojima Productions flaunted their new logo – a cyberpunk skull encased in a stethoscope-style helmet – to further distance themselves from Konami. Ridding themselves of the Metal Gear Fox, so tied up with the Metal Gear series, Kojima Productions had died and been reborn anew.

But, as with every newborn, Kojima Productions had to learn to walk. To begin making games, they needed an engine, and they sure as hell weren't going to use Konami’s. Kojima was at a loss. Creating an all-new engine would significantly delay any games he wanted to develop. With no one to turn to, and no engine to fall back on, he began to feel isolated and alone. That is until Guerrilla Games stepped in to save the day. The developer of games such as Horizon Zero Dawn, and Killzone, heard wind of Kojima’s slump, and, during a research trip to their studio in the Netherlands, offered up their own engine for him to work on.

So overwhelmed that his years in the industry could garner such incredible support, Kojima explained, during a PlayStation Experience panel in 2016, that he cried tears of joy when Guerrilla gave him access to their engine. He even named the adapted engine the Decima engine, after Japan’s Dejima port, a Dutch trading port where the Japanese conducted almost all international trade during the Edo period. The name represents the connection between the studios, and their shared belief in collaboration as the key to great games. It’s also why you can find all the holograms of Horizon Zero Dawn’s metal dinosaurs and protagonist, Aloy, throughout Kojima Production’s first independent title… Death Stranding.

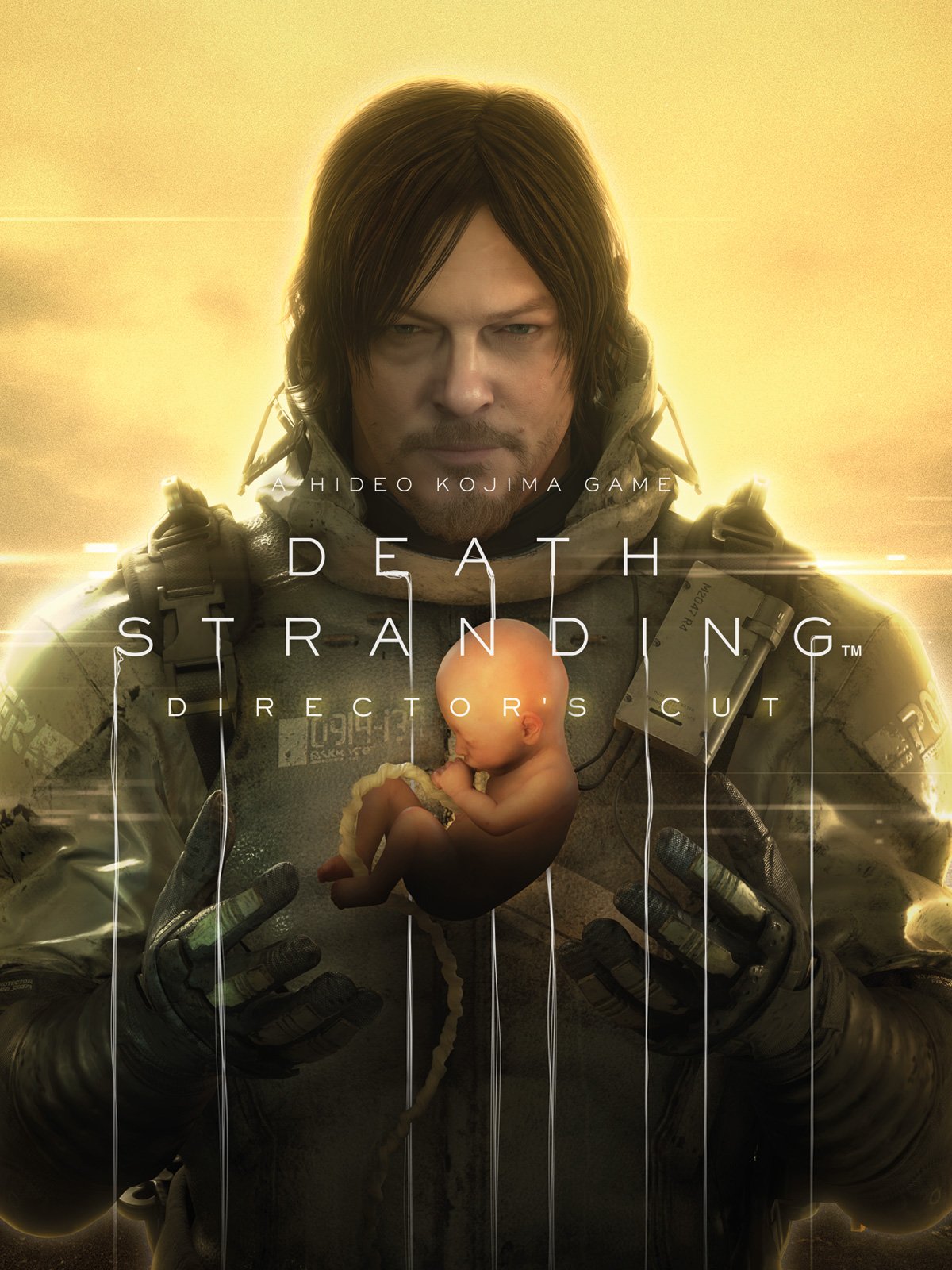

A Hideo Kojima Game

Death Stranding is jam-packed full of... Kojima. With long, drawn-out cutscenes in Kojima’s signature cinematic style, an allegorical, sometimes impenetrable story strewn with themes of anti-war, anti-nuclear weapons, and a soundtrack from some of his favourite musical artists such as Low Roar, Silent Poets and CHVRCHES. In true Kojima fashion, the gameplay prioritises stealth over combat and even boasts a hidden cameo by the maestro himself, as well as several name-dropping item descriptions.

You play as Sam Porter Bridges, a freelance courier performed by Norman Reedus, who traverses a post-apocalyptic North America, delivering packages to citizens hunkered in deep underground megacities. An extinction event known as a death stranding has laid waste to Earth’s surface, leaving waves of BTs [goo-like monsters which have emerged due to the death stranding] and storms of dangerous Timefall [an ink-like rain substance which rapidly ages whatever it touches]. In Death Stranding, the world is broken. Civilisation disconnected… Sam is here to reconnect it. Circumventing terrorists, bandit groups known as MULES, and all manner of terrain, the goal, as with all Kojima fare, is to avoid conflict at all costs or risk damaging that all-important stack of pizzas that you’ve lugged halfway across the continent.

Featuring a star-studded ensemble cast including the likes of Mads Mikkelsen, Lea Seydoux, and Margaret Qualley, the game is a cinephile’s wet dream. However it’s slow... arguably its biggest downfall. But if you slog through the BT marshes, the hours of cutscenes, to fatal storms of Titanfall, and the treacherous terrain, odds are you’ll discover what the game is truly about: connection.

Rarely speaking at the game’s beginning, more grunting in Reedus’ true to form style, Sam is paired up with Lou, a defective Bridge Baby [BB] – an unborn fetus used to identify, and assist in evading BTs. After a botched body-delivery mission results in an explosive phenomenon known as a void out [in this world, bodies are as nuclear as bombs], Sam dies, ingloriously. Yet as a repatriate, he has the ability to come back to life, swimming his soul through the world of the dead, and re-inhabiting his body. Tasked with establishing the chiral network, an internet-like communications system which spans the continent, Sam ventures into the wasteland with BB on his belly and deliveries on his back [or truck, bike, or even a rideable hover sledge if you fancy], fulfilling his namesake by bridging the gaps in society.

As the game opens up, Sam opens up, and we find out that his past is as enigmatic as Kojima’s storytelling. He had a wife who killed herself and their unborn child. As a direct result, Sam has disconnected himself from people, from relationships, preferring to travel the wasteland than interact with others. At the start of the game, Sam doesn’t hug, he doesn’t touch, he barely talks. Yet, as he forms a bond with BB, he begins to reconnect to the world and its inhabitants, establishing a surrogate family with his eclectic array of Hollywood friends.

Lea Seydoux, Guillermo Del Toro, Margarat Qualley and Nicolas Winding Refn in Death Stranding

Featuring tools of evasion such as BB, who can detect nearby BTs much like a canary in a cave, and an extensive knockout system to take down humans, with rubber bullets, and distraction tools such as decoy packages, Death Stranding is the evolution of Kojima’s pacifistic approach to combat. It encourages players to seek out non-lethal methods of taking down human enemies with strict punishment if they cause death, whether intentional or not. In the world of the game, when humans die, their bodies, if left to rot, are eventually consumed by BTs, causing a void out – an intense and violent explosion – which leaves a city-wide crater completely inaccessible to the player.

Death Stranding is about surviving through connection. Not violence. Through its online capabilities players can interact with other players, building structures and leaving messages to assist in their respective journeys.

While at first, the player-on-player interaction seems somewhat inconsequential, it becomes increasingly vital. There were many times when I found myself lost, with no battery pack to charge my power skeleton, or not enough stamina to wade through a shallow river. Finding a rope or a ladder left by another player saved my socks more times than I can count. Especially when traversing the dangerous heights of the Mountain Knot City area.

Through these interactive techniques, which span growing BT repellent mushrooms with your own urine, to simply leaving a “Speed Up” sign to give your vehicle a helpful boost, Kojima fully realises his career-long vision of making a game about connection rather than conflict. Like Dunkirk, both the movie and the historical event, in which allied soldiers and civilians had to collaborate to rescue a score of beached troops, the point of Death Stranding is to work together to avoid the loss of human life. According to Kojima, in Death Stranding, as in Metal Gear, “guns [are] not the answer. Escape is a form of resistance.”

Conclusion

Death Stranding isn’t just a video game. It’s a Hideo Kojima game. Working with friends and artists, game developers and long-time collaborators, he effectively interweaves cinema, music, art, design and technology to create a unique interactive experience. Where so many AAA games nowadays encourage you to fight, to be the last one standing in a Fortnite battle royale, riddle your opponents with bullets in Call of Duty, or slaughter countless enemies in gruesome chainsaw combos in Doom, Death Stranding is about connecting with the world, with players and characters on a human level.

Death Stranding is a game made by a true auteur. Fueled by Kojima’s anti-war sensibility, dressed up in his favourite pop culture references, and built around evasion – the foundations of his pioneering design heuristics – it is the culmination of everything he achieved with Metal Gear and more. And while it has problems, as mentioned, it’s slow, the storytelling is obscure, and the dialogue and meta-narrative don’t always mesh, it is Kojima through and through, unrestrained by studio interference. And for better or for worse, the game shines for it.

Intrigued to discover the added Kojimarisms in Death Stranding’s Director’s Cut, and with the recent news that there’s more to come, with the announcement of Death Stranding 2 at last year’s The Game Awards, we at Sabukaru.Online are excited as ever to continue this journey of collaboration. Connecting, with culture, people and stories through the lens of a master.

About the author: Simon Jenner

Writer, screenwriter and lover of all things Japan, Simon Jenner explores stories in art and culture. Connect with him for articles about film, anime, gaming and more.

Article formatted by Alberto Zaccharia