Hiromix: Shaping the Identity of 90’s Japanese Female Youth

A quick look into Japanese pop culture and they're everywhere. Representations of teenage women in paintings, album covers, graffiti, anime, manga, magazines, video games, commercial messages and a whole lot of cultural products.

Today, the image of the teenage student and the paraphernalia that surrounds her is synonymous with contemporary Japan, at least, the Japan that is massively known in the west.

However, when we look at these familiar and popular images of young Japanese women, we must ask ourselves if we really know the real people behind those media icons, if we really understand and are able to recognize their true identity over the one that the pop machinery built for them.

And no other was able to communicate this identity, this true identity of the Japanese youth better than the photographic work of "Hiromix", Hiromi Toshikawa.

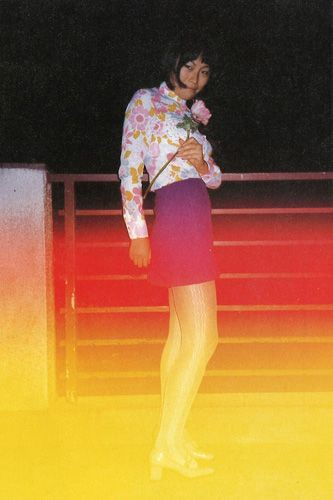

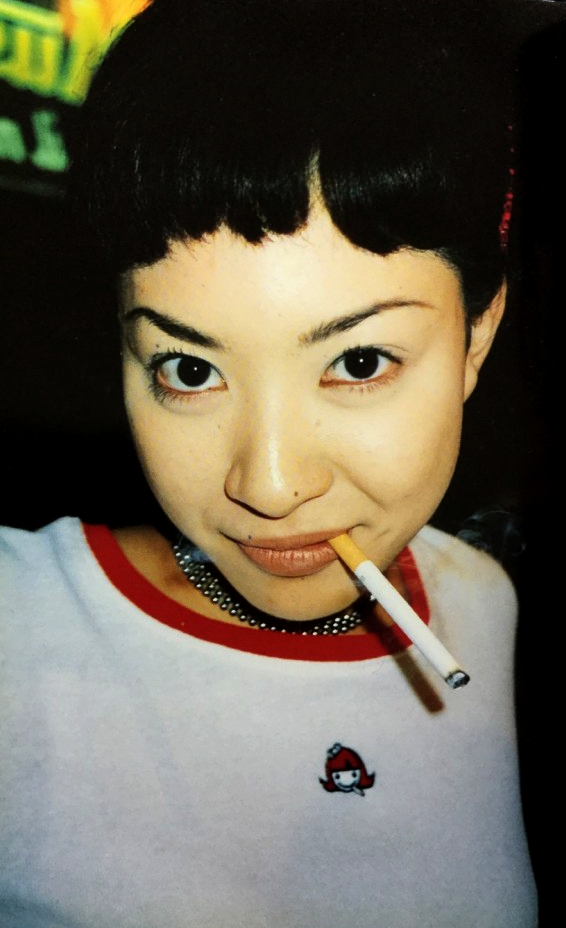

Hiromix self-portrait from the book, Hikari (1997)

Hiromix self-portrait from the book, Girls Blue (1996)

Born in 1976, Hiromix is a Tokyo photographer who, along with Yurie Nagashima and Mika Ninagawa, is considered the main instigator of a photographic movement in which, fostered by a cultural shift, point & shoot cameras and the 'Purikura' (Print Club) culture, driven by kiosks and coin-operated photography machines, Japanese teenagers, and especially, teenage Japanese women from the early 90's, took center stage in a new visual language.

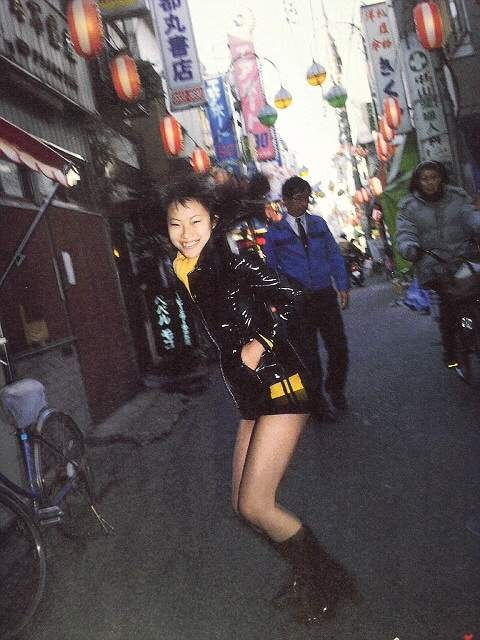

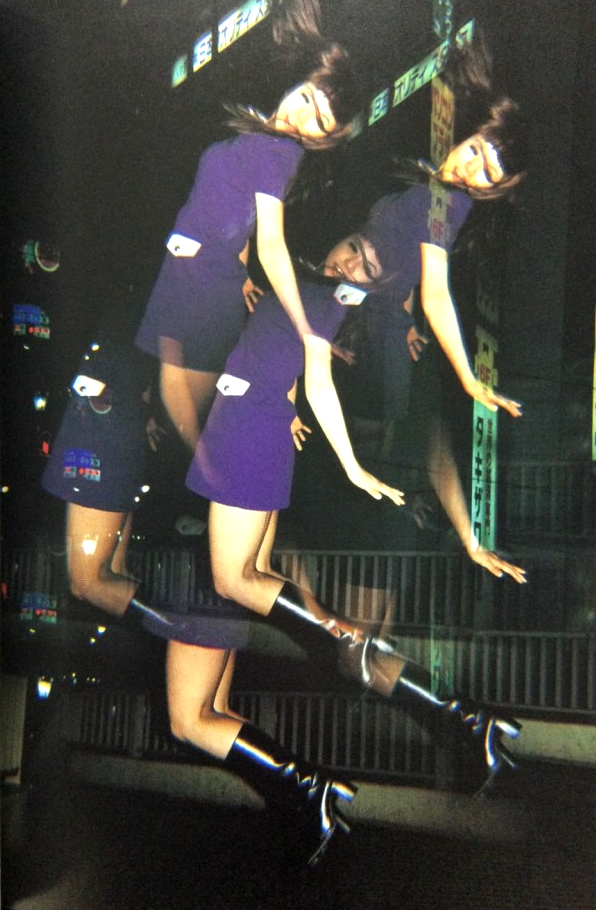

Photograph from Seventeen Girl Days (1995)

While still part of an underground movement, her breakthrough came through more traditional means, when she won the 1995 New Cosmos of Photography Award, sponsored by Canon and selected by Nobuyushi Araki, the icon of erotic photography and Japanese photo diary.

Her awarded, "Seventeen Girl Days", consisted of 50 pages of photographs from her daily life as a high school senior. Self-portraits in her underwear, objects in her room such as her television and stuffed animals, photographs of her half-eaten breakfast, blurred portraits of her friends and daily activities, images that helped to build a world of the intimately feminine, personal and unknown to a nation accustomed to overly sexualized representations of women, created, of course, by men.

Photograph from Seventeen Girl Days (1995)

In the same year, Studio Voice magazine, specialized in youth movements, but with a base of middle-aged photographers who had nothing to do with their readers, issued a volume dedicated to young photographers, trying to find a new platform.

Hiromix, then 18 years old, was one of those photographers who answered the call and her work reached a commercial milestone with the publication of volume 236, captivating an audience of youngsters, photography aficionados, critics and central figures of the medium alike like Takashi Homma. Such reception led to volume 243 of the magazine under the title "We Love Hiromix", dedicated entirely to her work, with a profile written by family, friends and Nobuyoshi Araki himself.

Excerpt from Studio Voice 243, "We Love Hiromix" (1996)

Hiromix's success and her influence on photographic culture was no coincidence. After the explosion of the economic bubble of the 80's, Japan, during the 90's, plunged into an economic crisis that shifted the focus on those who make and shape pop culture.

During the economic boom, men and the salaryman became the central figure on how entertainment and culture were consumed. The big companies that flourished during this time and the salaries they paid, helped the salaryman feed all commerce, from bars and restaurants, to art galleries and their exponents.

Consequently, women took on a secondary, traditionalist and almost ornamental role. The modeling industry and the growth of the idol phenomenon of merely "cute" idiosyncrasy, cemented how women were seen by their society.

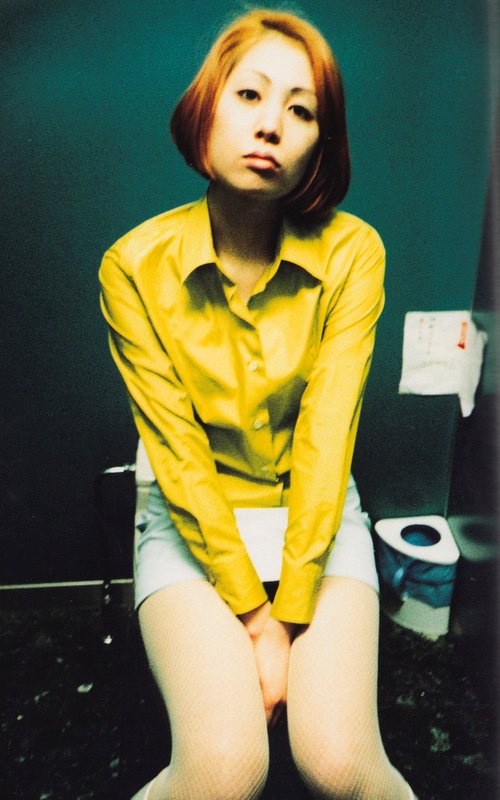

Hiromix self-portrait, from the book Girls Blue (1996)

It is not surprising that most famous photographic expressions of that time followed this trend. Proof of that are the portraits of Nobuyushi Araki, Eikoh Hosoe and Shoji Ueda that, while being no less artistic, represented a masculine point of view.

When the economic bubble burst in the early 90's, the salaryman and his abundance stopped being the engine that drove the economy and the companies, shifted their focus from him, to his sons and especially, his daughters, hoping to create an adolescent consumer culture while elevating them as trend makers and sexual icons.

Portrait form the book, Girls Blue (1996)

Cultural shift in place, technology played a huge part building new forms of expression for teenage women, specifically photography. In 1990 point & shoot cameras, cheap, fast and easy to carry cameras were introduced and in 1995, Atlus Amusement Co. presented their “Print Club” (known as Purikura) machines, creative photo booths that became massively popular among youngsters.

In this environment, female Japanese teenagers began developing a unique aesthetic and artistic personality, where representations of their bodies and life belonged to themselves and not to the media.

Hiromix, with a Konica Big Mini camera and photographs processed in local kiosks, was able to condense this feeling of independence and adolescent freedom that the establishment photographers (mostly middle-aged men) couldn't access. A new movement called “Onnanoko Shashin” (Girly Photography) started to gain traction.

Excerpt from Studio Voice 243, "We Love Hiromix" (1996)

The term Onnanoko Shashin, coined in 1996 by the photography critic, Kōtarō Iizawa and compiled in his 'Shutter & Love: Girls are Dancing On in Tokyo' of the same year, tries to explain why young women began to take photographs in the privacy of their world and far from the common places where they were regularly photographed, like familiar and school year photo books.

Kōtarō Iizawa, described the changing times in which the women of the movement grew up (mostly, born in the 70s): an environment characterized by superficiality, consumption, the weakening of the sense of space and even the typical patriarchal values of Japanese culture.

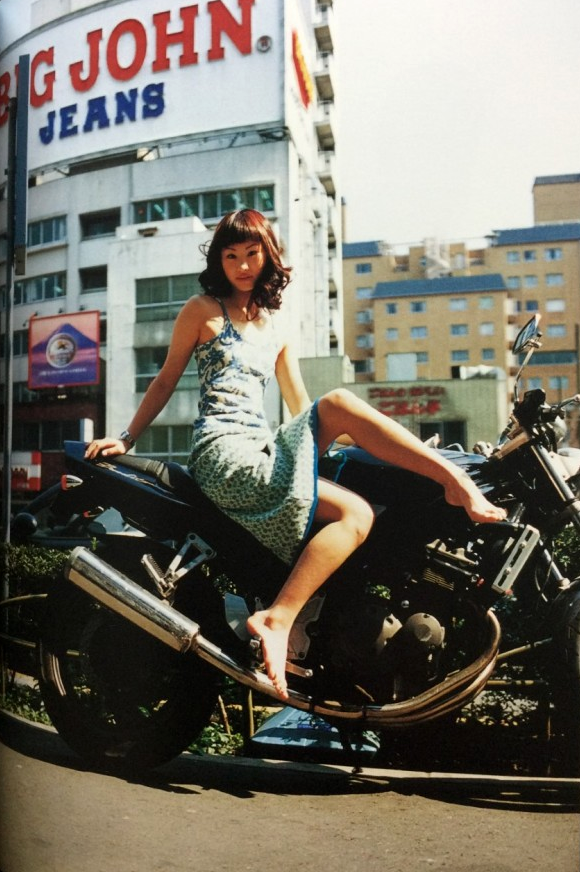

Snap from the book, Hikari (1997)

When the bubble burst, the overload of pop information developed an innate aesthetic vision in young urban women, empowered by a new revaluation of femininity, against the machismo culture that were perpetrated through the 80's. Fashion, music and photography were their main artistic expressions.

When it comes to the technique of these new photographers, Kōtarō Iizawa argued that women preferred the inspiration and opportunities related to point & shoot cameras, automatic and easy to use, in contrast to male photographers, who preferred methodology and structure, related to SLR cameras. This was called “the female principle”.

Snap from the book, Hikari (1997)

Onnanoko Shashin, has been widely criticized and even rejected by its members, such as Yurie Nagashima (who was the first photographer under this trend), who argues that the term suggests that women do not have the technical skill to handle professional equipment, which was obviously not true, they decided to use point & shoot cameras because they were effective for their work and expression.

That is why in 2000 when Hiromix, Mika Ninagawa and Yurie Nagashima as 'Onnanoko Shashin' won the Kimura Ihei Award, one of the most important photography awards in Japan, Yurie Nagashima considered rejecting it, since she believed their work (was seen among the photographic medium as one more representation of "cute", but ignoring its feminist message.

In that sense, it is important to note that, while Onnanoko Shashin, is a useful term to recognize the movement and its protagonists, it doesn’t express their intentions, nor meaning.

Hiromix, did not openly challenge the patriarchal structures of her society, but was indeed feminist. Her approach tries to recover the representations of the daily life of Japanese teenage women and build a real image of their identity, far from the cute, shallow and conformist agenda of the media.

Portrait from the book, Hiromix Works (2000)

Seeing through her photos is reaching a sense of daydreaming, a special feeling of living the moment. Their protagonists escape from reality and capture a vivid memory of momentary freedom that can materialize on the most mundane and familiar object but even when capturing a memory, there’s no space for nostalgia, everything is a flash, there’s no time to separate reality from the daydream. Before you realize, the world they built has melted away.

Hiromix, did not openly challenge the patriarchal structures of her society, but was indeed feminist. Her approach tries to recover the representations of the daily life of Japanese teenage women and build a real image of their identity, far from the cute, shallow and conformist agenda of the media.

Seeing through her photos is reaching a sense of daydreaming, a special feeling of living the moment. Their protagonists escape from reality and capture a vivid memory of momentary freedom that can materialize on the most mundane and familiar object but even when capturing a memory, there’s no space for nostalgia, everything is a flash, there’s no time to separate reality from the daydream. Before you realize, the world they built has melted away.

This world does not compare with the expectations for the future nor with what Japanese society, incredibly rigid with teenagers and their expectations.

"They are not interested in contributing to the Gross Domestic Product of Japan other than paying the restaurant bills," she declared before comments from people who positioned her (in her opinion, wrongly) as a spokesperson for her generation.

Portrait from the book, Hiromix Works (2000)

Hiromix self-portrait from the book, Girls Blue (1996)

In 1996, a year after her discovery, her first photobook, “Girls Blue” was edited, which consisted of 122 pages of photographs from a selection of more than 30,000, taken since she was 17 years old, including those previously seen in “Seventeen. Girl Days ".

Snapfrom the book, Girls Blue (1996)

At first, the book and her work were not received with much sympathy among the most recalcitrant part of the photographic community, calling it "amateurish", however, the visual language of Hiromix was not meant to praise perfection but to appreciate imperfection and, like her contemporaries, even though she was perfectly capable of use specialized equipment, she preferred her Konica Big Mini and the novel disposable cameras, in a disdain for the “smokescreen” of complex photographic processes.

Naturally, this form of photography that removed the barriers of technique and process, prompted teenagers across Japan to explore their own style of photography, unleashing a creative wave based on the ordinary, with exponents such as Maki Miyashita who expanded the concept of teenage girls and their spaces, Kayo Ume who explored the daily life of Japanese children and Tomoko Sawada, merging identity, essence, personality and social significance with her ID400 series.

During the years leading up to the 2000s, Hiromix expanded her creative spectrum into advertising, working with clients such as alternative radio station J.Wave and Sony Music, with her portraits of electronic vanguardists, Squarepusher and Aphex Twin, and model photography with the photobook , Japanese Beauty, despite being a vocal critic of this photographic genre.

Aphex Twin and Squarepusher by Hiromix, Sony Music (1997)

Aphex Twin and Squarepusher by Hiromix, Sony Music (1997)

In addition to her photographic work, she explored music with an album, Hiromix 99 '(1999) and three EP's with Kiwa Kagata as The Clovers, and two EPs on her own, "Oh My Lover" (1996) and "Hello I Love You!" (1999). All works aesthetically and sonically related to the Shibuya-kei, retropop and mod revival movement, popularized by musicians like Flipper’s Guitar and Pizzicato Five.

In 2000, Takashi Murakami founded SUPER FLAT, the artistic movement that ended up ruling Japanese aesthetic and psyche during the first decade of the 00 '. Hiromix's work were included in SUPER FLAT's presentation exhibition at Shibuya PARCO Gallery with artists like Masafumi Sanai, Chikashi Suzuki, Aya Takano, Katsushige Nakahashi and Murakami himself, solidifying her position as part of the vanguardist artistic generation for the end of the century.

In 2000, Takashi Murakami included Hiromix work as part of the SUPER FLAT exhibition at Shibuya PARCO Gallery together with artists like Masafumi Sanai, Chikashi Suzuki, Aya Takano, Katsushige Nakahashi and Murakami himself. Being part of SUPER FLAT, the artistic movement that shaped an entire generation of Japanese artists (and still does), Hiromix, solidified her position as part of the visual language that helped build Japan’s position as an artistic epicenter during the 00’s decade.

Portrait form the book, Hiromix Works (2000)

In line with the SUPER FLAT manifesto, which explains how Japanese visual culture is not taught in art schools, where art was taught from the Western point of view, Hiromix developed a distinctly Japanese body of work, “the 2D feeling", as Murakami names it, that pop products transmit, such as manga, video games and anime.

During the 2000s, Hiromix established herself as a cult figure with eight compilation books of her work, five national exhibitions, (including one at the Tokyo Museum of Contemporary Art) meanwhile her creativity embraced new frontiers: from design, creating album covers for The Cribs, to fashion, working with global brands like KENZO, and even acting, with a cameo in Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation.

Snap from the book, Girls Blue (1996)

Much has been said about how Hiromix's work signified the selfie culture for the 90's before social media. Although there's some kind of resemblance, her current influence is much more noticeable in young Japanese photographers who, like her, take advantage of the technological facilities to tell their own perspective of the environment that shapes them.

Young photographers such as Yoshiyuki Okuyama, Sara Masuda, Ada Yasuya, the “emoi” movement and especially, Masumi Ishida, develop a new perspective, fostered by the expansion of social media, this time not telling a story of turbulent times, but a story of stability even opportunities.

Although Japanese photographic culture and its female protagonists have existed since the invention of photography as a vehicle of expression. Hiromix and her peers brought a new point of view that broke with paradigms of how the identity of the teenage women should be understood, far from the pop icon and much closer to their own realities and most importantly, told from their own visual story.

About the Author:

Leonel Martínez is a social media consultant and a writer living in Mexico City. Japanese culture, graphic design and art aficionado. Describes himself as a "cultural worker".