No Skateboarding! – Nobuo Iseki Documents Tokyo’s Skate Community On Polaroid Film

If the relationship between Japan and skateboarding were a 2013 Facebook status, it would be “It’s complicated.” While the Tokyo Olympics 2020 [2021] showcased the incredible skateboarding talent coming from Japan, the sport and its surrounding culture are still widely prohibited and unwelcome in Japanese cities.

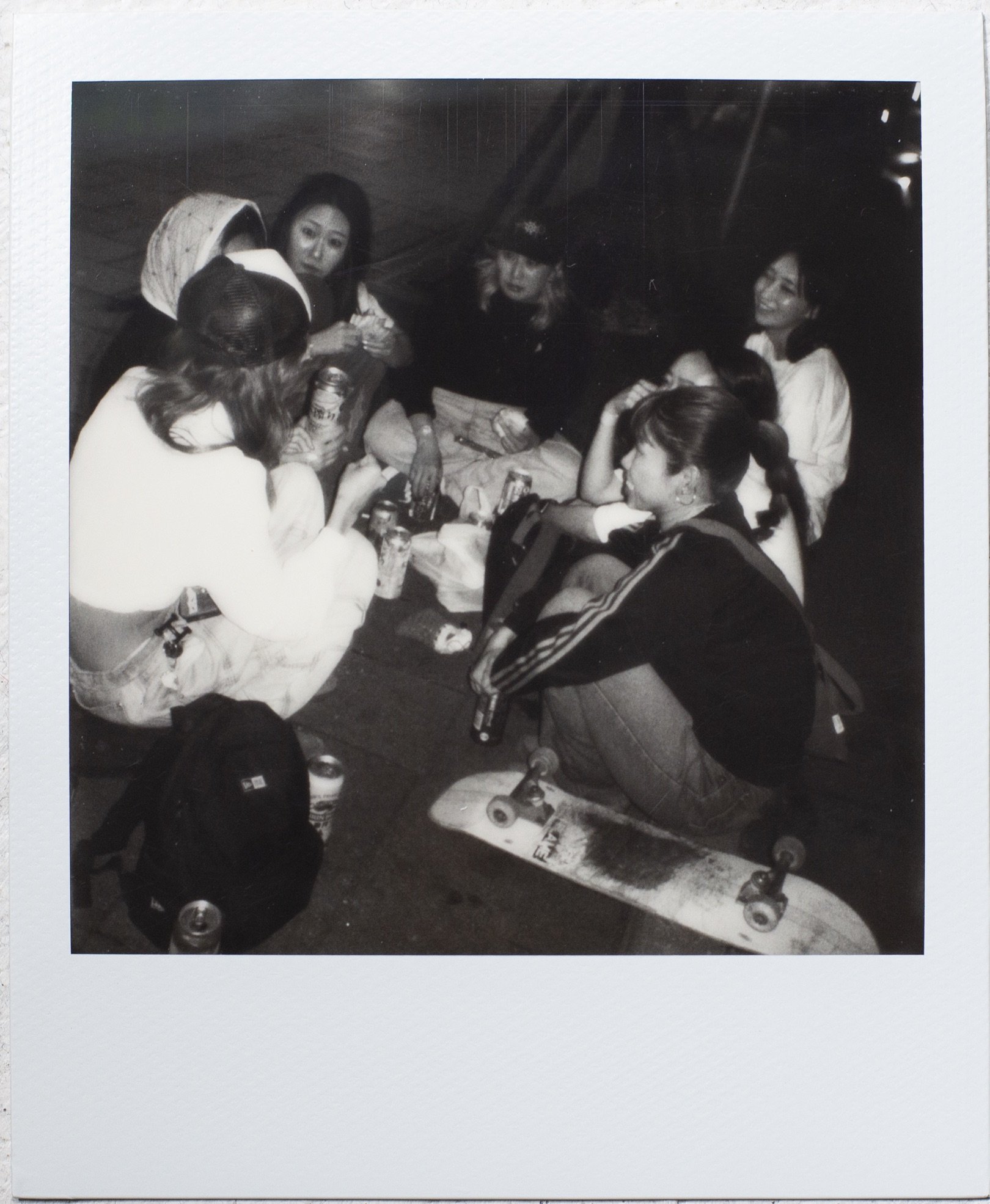

Amid the many “No this” and “Don’t that” signs in Tokyo, red crossed-out skateboarding pictograms can be spotted at every public spot or park. Despite this, there is a vibrant and proactive skateboarding culture in Japan. On weekends, you can see young people hanging out in centers like Shibuya, Naka-Meguro, or Shinjuku with a can of Asahi and a skateboard. Due to legal issues, skateboarders in Tokyo are always on the move. Skating in one spot will likely be interrupted by local police officers or angry locals, prompting the search for a new spot. Nevertheless, this doesn’t discourage the skateboarding community. Their enthusiasm is as high as in skateboarding metropoles like New York City, Los Angeles, Paris, or Barcelona.

Photographer Nobuo Iseki has been capturing the scene for over 20 years. He documents the activities of some of the most exciting skateboarders in Japan in his own magazine, Pancake Skate Mag, as well as for internationally renowned outlets like Thrasher and Polar Skate. For his latest project, he joined a worldwide collective of photographers to highlight skateboarding’s creative energy and rebellious spirit. The contributors, from five different major cities [Los Angeles, London, Barcelona, Paris, and Tokyo], all documented the communities in their respective cities on Polaroid film. Through the instant format of the medium, the photographers were able to capture unfiltered snapshots of the culture and its people. All Polaroid photos could be seen during the L’habitat exhibition in Paris.

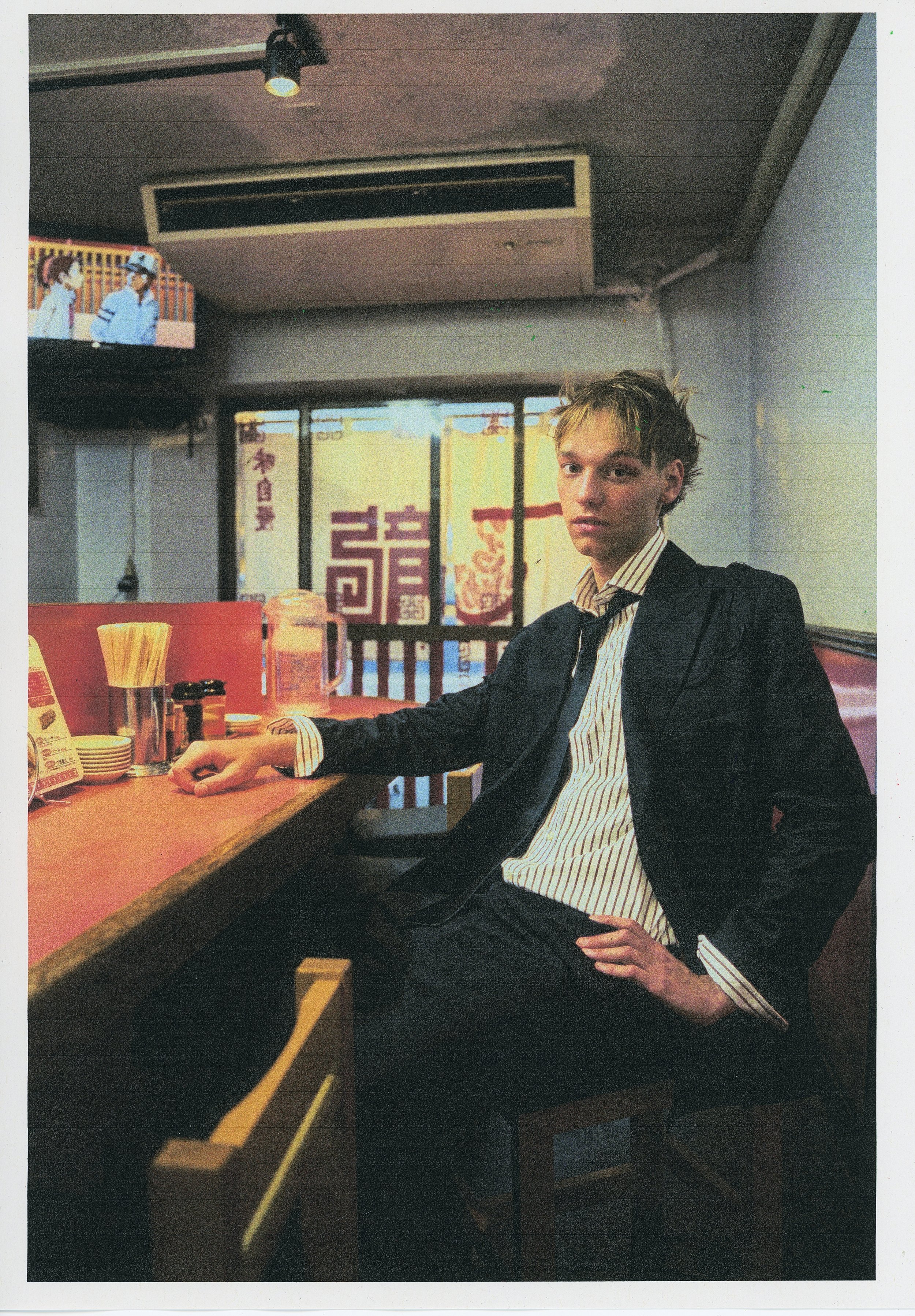

In his photos for L’habitat, Nobuo Iseki aimed to capture the life of skateboarders in Tokyo, whether it was the repressing signs, a skate spot, or somewhere where they eat and party. “I wanted the individual images to combine to show a journey more than single tricks,” he explained.

Iseki believes Tokyo offers a unique landscape for capturing the skate scene. As skateboarding in Tokyo is still not very mainstream, he says the background is as important as the tricks when presenting Japanese skateboarding to the world. “The landscape of Tokyo is really interesting visually because you have new right next to old. There’s so much history and Japanese people care about the details. The city is so clean and almost sterile. Even the noise of skateboarding freaks people out.”

As we explained in our 2022 article on skateboarding in Tokyo, the Olympics, and the Gold Medal in the first-ever Olympic skateboard competition for the most famous Japanese skater, Yuto Horigome, have slightly changed the perception of the sport in Japan. Instead of viewing this culture as vulgar, Japan is starting to consider it a sport. Though these baby steps are well-intentioned, Tokyo is still on the back burner.

Nobuo Iseki shares this observation, noting the literal other side of the medal: “Before the Olympics, skateboarding was ignored in Tokyo. Now a lot more people accept it, but because of that attention, more people are calling the cops on us and getting us kicked out of spots.”

With police and locals being even more vigilant, there are also restrictions on his work as a photographer. Shooting during the daytime is difficult because you only have a few tries before you’re kicked out of a spot. You don’t even have time to test your flashes. Furthermore, it’s hard for the skaters themselves because they have to choose tricks they know they can land. However, he believes this sense of danger created the whole Eastern style of skating.

To circumvent these difficulties, much of Tokyo’s skateboarding takes place at night or during holidays when big office buildings and otherwise tightly surveilled spots are abandoned. “Sometimes we’ll try to hit ‘forbidden spots’ like museums or big office buildings on New Year’s Day when there’s no security or go out at 3 am to shoot a photo, but even then, you only have a few tries before you’re kicked out. After Yuto dropped that part filmed entirely in Tokyo at night, everyone started hitting me up to shoot photos super late at night. I told the younger skaters that I’m getting too old for those midnight missions.”

For the future of the community, Iseki has a positive outlook. After the Olympics, he saw a growing interest among young people. “The other side of the Olympics coming to Tokyo is that I’m seeing a lot more girls skating and progressing quickly. It felt like all of a sudden there were so many girls coming up in Japan after the games. They’re not only going out in the streets, but they’ll send me photos and videos to get my opinion. When I was younger, you’d only see guys hanging out at the convenience store after a session. Now you’ll see a bunch of girls hanging out, playing S.K.A.T.E., drinking beers. They’re not only progressing with their tricks, but the community is growing. You can tell that skateboarding isn’t just a sport to them.”

In collaboration with Polaroid