Techno-Orientalism: Decoding Japan's Misrepresentation as a Cyberpunk Utopia

Japan fascinates tourists with its bright advertising signs, robots, and high-speed trains. Consequently, visitors often label their Instagram snapshots with captions like 'Living in the future' or 'Cyberpunk city.' To understand this phenomenon, one must consider the emergence of cyberpunk within the context of international geopolitics in the 1980s.

NINTENTO AND THE FEAR OF LOSING

Applying a neon filter to a photo of Shinjuku's skyline can indeed create a futuristic vibe. However, those who spend some time in Japan quickly realize that the nation is not as futuristic as many believe. Although Japan has a significant technological sector, beyond the bright LED lights there exists a world of bureaucracy and tradition. To grasp tourists' perceptions of Japan, it's essential to explore the cultural industry of the '80s

During this period, Japan experienced significant economic and technological growth, which led politicians, artists, and filmmakers to consequently turn their attention to Japan. The perspective encompassed not only appreciation but also the fear of losing control. Particularly, the rapid technological development sparked anxiety in the West, as it represented an uncontrollable, swiftly evolving force.

This fear aligns with the rise of companies like Sony and Nintendo in the late '80s and is reflected in the culture industry through the emerging genre known as "Cyberpunk," which often depicts a lawless, grim, and corrupt future where society is alienated by its technological advancement.

FROM BLADE RUNNER TO TECHNO-ORIENTALISM

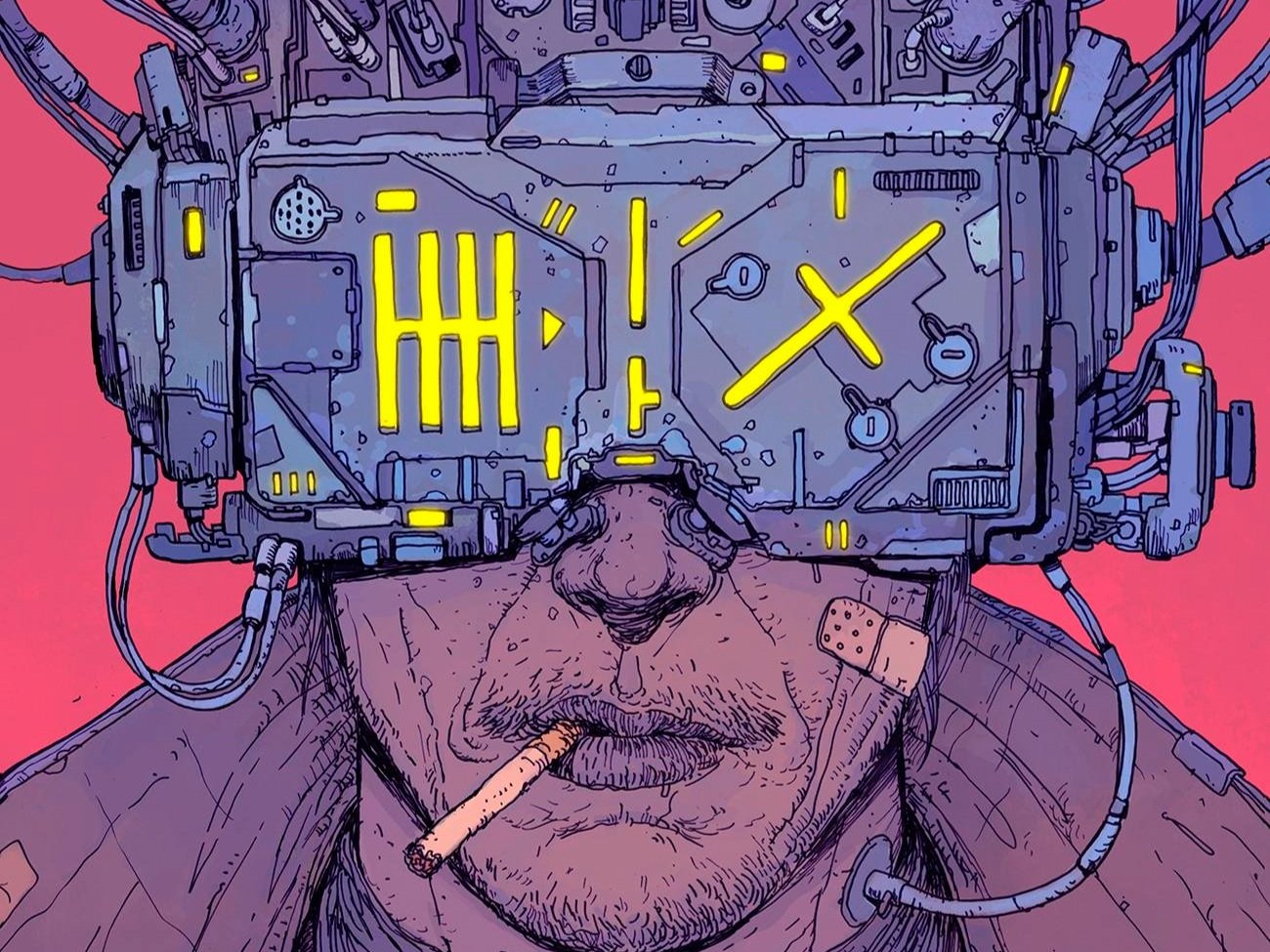

A prime example is the 1982 film Blade Runner, set in a dystopian futuristic L.A., where the cityscape is heavily influenced by Asian corporations and aesthetics. The city exemplifies a future dominated by East Asian technology, featuring many symbols associated with a term called “Techno-Orientalism”.

This term builds on the concept of classical Orientalism defined by literary scholar Edward Said. In Orientalist portrayals, the Orient is often depicted more in terms of Western misconceptions than its actual reality, frequently characterized as backward and exotic.

Jean-Léon Gérôme's 1879 painting, The Snake Charmer, exemplifies how the Western perspective often misinterprets the East as mythical and exotic.

However, this framework doesn't entirely apply to Japan, given their undeniable technological advancement in the 80s. As a reaction to the fear of losing control, Techno-Orientalism portrays Asia, especially Japan, as technologically advanced yet losing its humanity.

This perspective on the East is pivotal in the Cyberpunk genre, which frequently portrays Asian characters as robotic figures in a dystopian future. These films present a post-human world where Asian-coded characters are depicted as devoid of emotion. In cyberpunk films like Cloud Atlas and Ex Machina, Asian women are often sexualized as cyborgs, depicted as powerful yet sexually submissive.

Consequently, Cyberpunk films commonly feature heroes battling against technologically advanced but emotionally stunted societies, often illustrated with Asian-coded elements or settings.

CYBOGS AND TRANSHUMANISM

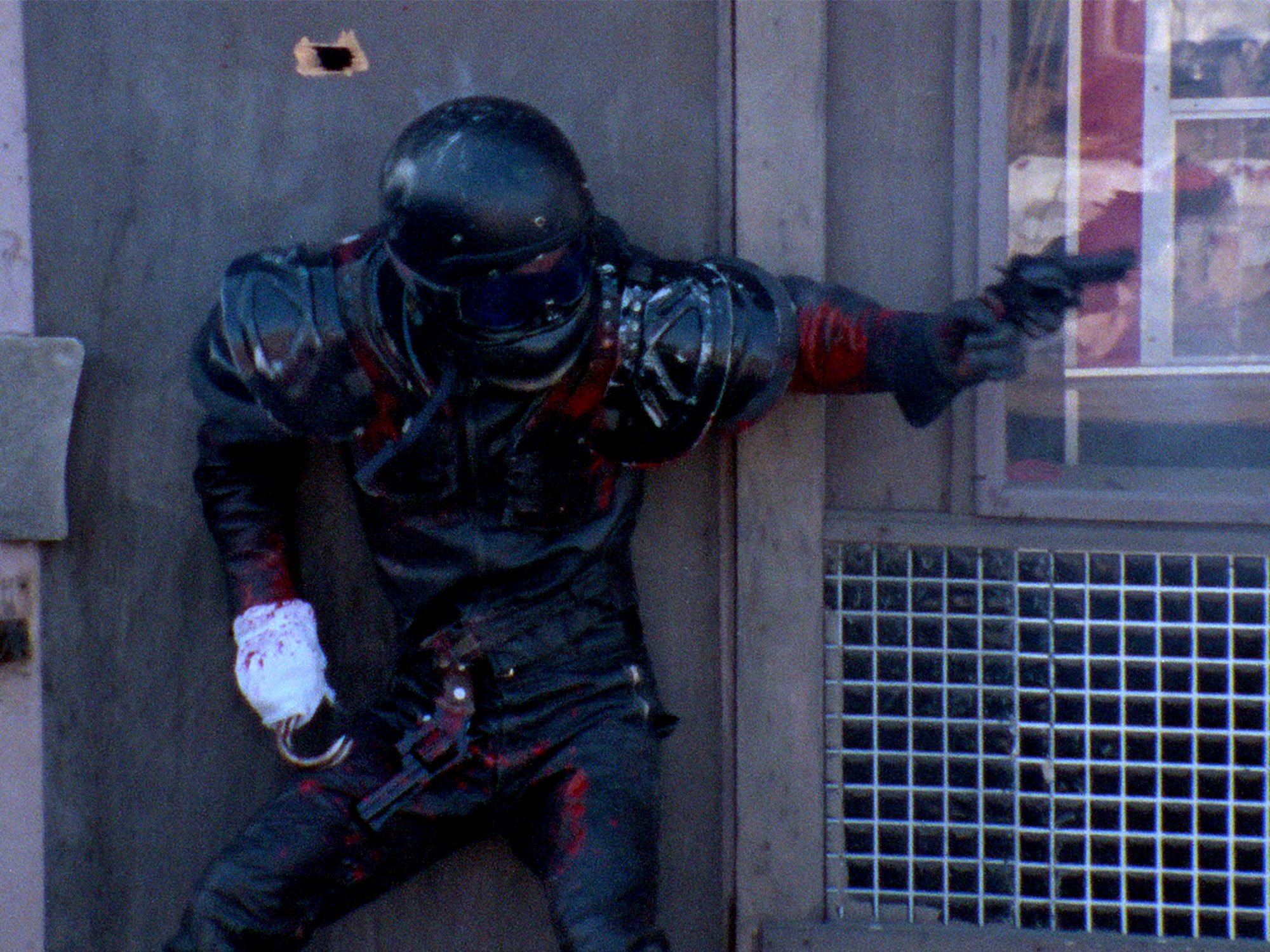

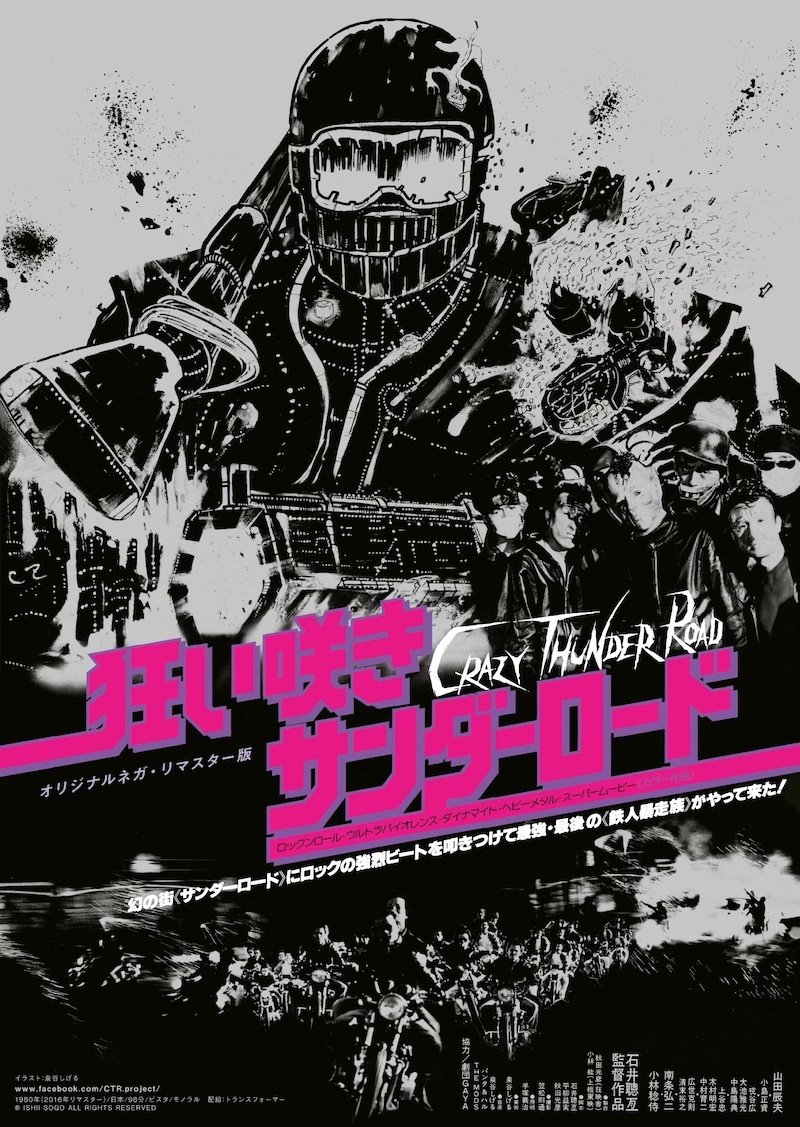

Nonetheless, Japan's technological and economic surge was real. And this evolving future was captured in movies like Crazy Thunder Road and Death Powder, though embodying more punk than cyber.

Thus, Japanese independent filmmakers depicted this transformation, integrating elements of cyberpunk, yet from the "eye of a tiger," offering an authentic, internal viewpoint rather than a distorted external one.

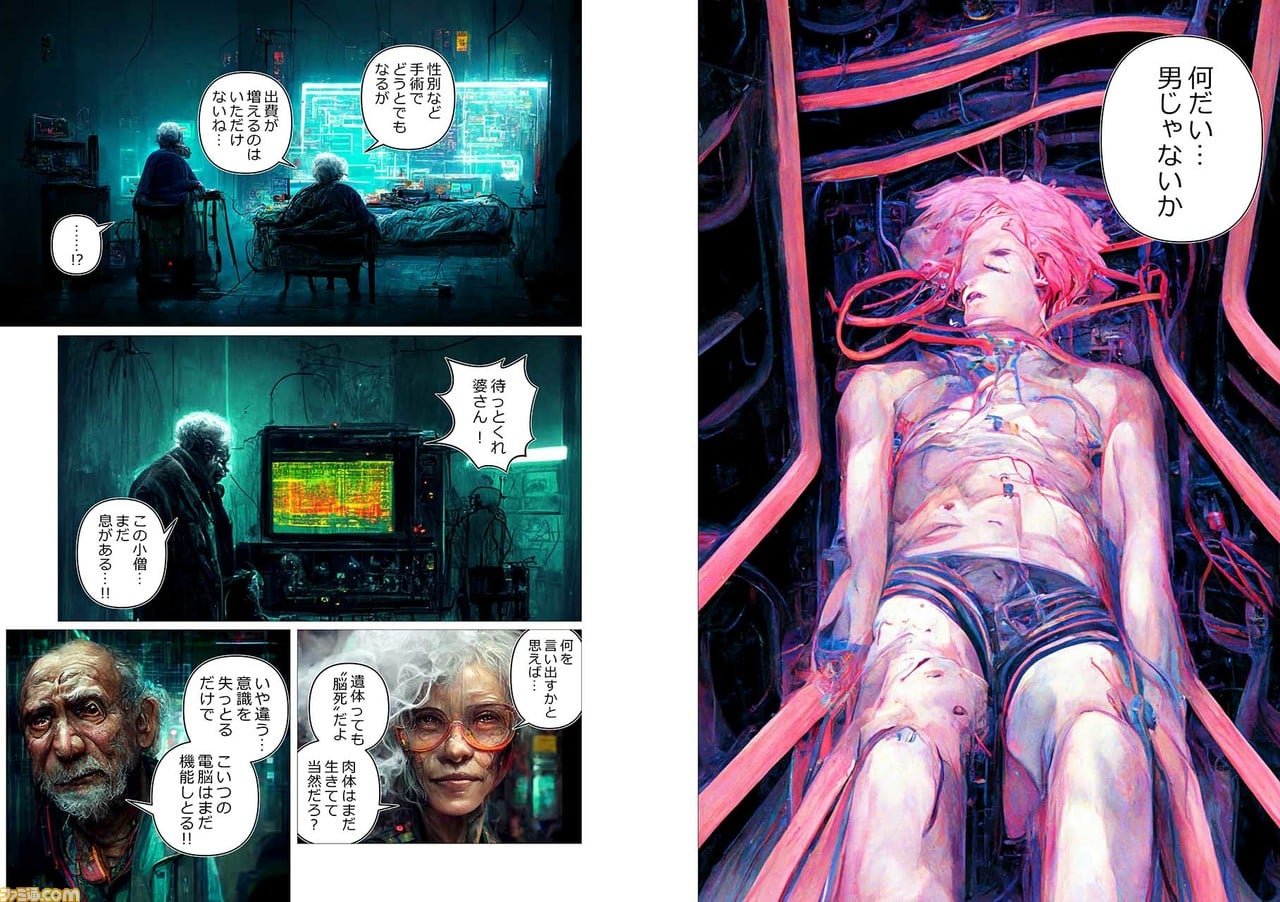

The classic later merging Japanese cyberpunk genre, notably portrayed by Shin’ya Tsukamoto's "Tetsuo: The Iron Man," in the year 1989 reflects also fears of excessive progress, though not from a techno-orientalistic perspective. The film blurring the line between human and machine, mirroring Japan's cultural shift in the '80s.

Japanese cyberpunk films address the era's fears differently from those in the West. They focus on concerns that their own technology and economy are developing too rapidly into a transhuman world. However, some argue that Japanese creatives have incorporated techno-orientalist ideas into their works, like "Ghost in the Shell" or "Akira".

BEHIND THE LED

Although the Japanese economic bubble burst in the 1990s, some fears and perceptions of Japan as an emotionless, cyberpunk nation have persisted. Criticizing Japan's portrayals as techno-orientalist should not result in viewpoints that ignore the Japanese technological sector or neglect the creativity and artistic value behind Cyberpunk. Instead, concepts like techno-orientalism should aid in reflecting on our cultural perspectives, also in modern productions such as 'Ghost in the Shell (2017)' and 'Cyberpunk 2077.'

Going beyond the technofetishization allows to discover the myriad other aspects that Japan has to offer, which are not always futuristic or dystopian but are still captivating.

About the Article:

This text is inspired by Brian Ruh's insightful contribution, "Japan as Cyberpunk Exoticism," in "The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture."