The Solitary Gourmet- The Ultimate Ode to Food

The Solitary Gourmet is TV comfort food. The series based on the intensely popular manga by Masayuki Kusumi and Jiro Taniguchi, owes its success to being deceptively simple, understated, and beautifully formulaic.

Our hero, Goro Inogashira in the original Solitary Gourmet manga.

Goro Inogashira played by Yutaka Matsushige in the live action drama.

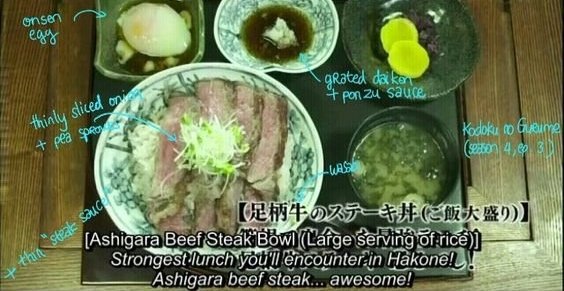

An unintentional crash course on Japan’s relationship with food, city life and its notoriously gourmet hole-in-the-wall eateries. There is no other place in the world for food like Tokyo, and no other series that devotes attention to a meal's minutiae like the Solitary Gourmet.

Not every TV show or manga needs a detailed account of its deeper significance, some things are enjoyable for the sake of well, just being enjoyable.

That’s what the show’s diehards say concerning its humble story chronicling the quintessential salary man,an intentionally average Gorō Inogashira, played by actor Yutaka Matsushige, as he takes time from running his mundane business errands as a European goods importer to sit down, relax, and enjoy a solid homespun meal. In a world filled with madness, The Solitary Gourmet gives us the much-needed familiarity of an average guy doing gloriously average things.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF GORO: Japan’s Favorite Foodie

Each episode of the drama [if it can even be called that], occurs in two scripted segments: the first which sets the stage for our salaryman's daily errand [usually a delivery to a client], followed by some quaint exchanges with his customers, old flames, and neighborhood regulars.

This lull is broken by a sudden rise in action, our hero Inogashira gets hungry. That’s when our normally placid salaryman springs into action.

As his stomach begins to rumble, the hunt is on for just the right local spot to satisfy his cravings. Finally, the scripted portion of the episode ends with his painstaking appraisal of his grub through his stoic voice-over narration, finishing with Inogashira wistfully walking off-screen [solitarily of course].

As the seasons go on, the scripted episode is followed by a short bangumi style [a variety show, often featuring cheesy commentary] featuring Kusumi himself, the writer of the original Solitary Gourmet, going to the very same establishments as our fictional hero.

Kusumi gives us an enthusiastically detailed play-by-play of his dining experience, mimicking the attention to detail Gorō gives viewers, who live vicariously through every bite.

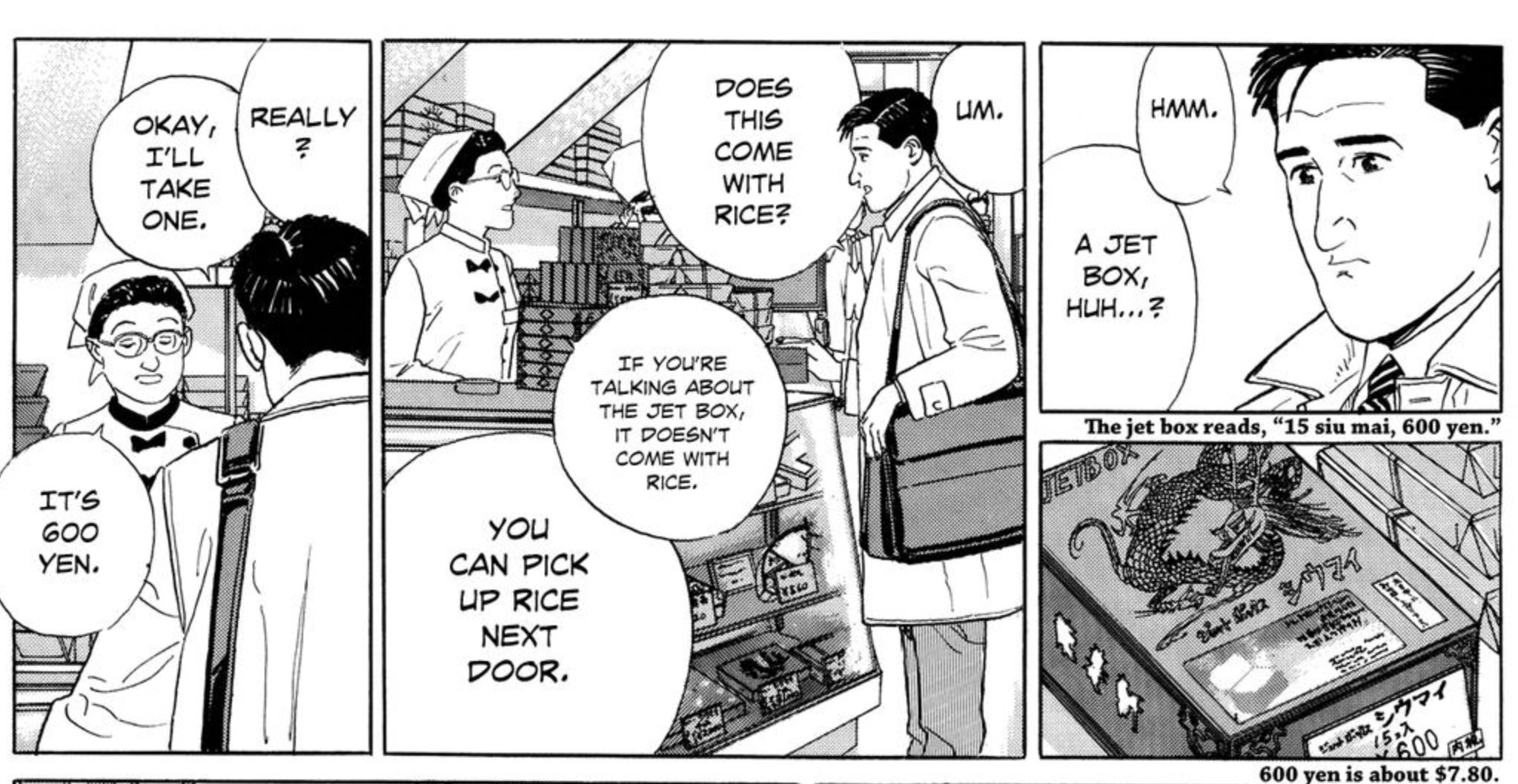

The Solitary Gourmet also lists the prices of each dish Goro consumes.

Nothing about the Inogashira is remarkable, and nothing about the restaurants are remarkable either [at first glance, at least].

The show's decision to dive deeper into the everyday act of eating makes it an unexpected insight into Japan's culinary landscape and attitude towards time, place, and even national identity, giving the viewer a better understanding through every meal Inogashira devours.

With that being said, we at Sabukaru dig into the finer points of The Solitary Gourmet's escapades.

NO PLACE LIKE HOME [ALMOST]- THE SOLITARY GOURMET AND THE SHITAMACHI

What sets each Solitary Gourmet episode apart from one another are the neighborhoods Inogashira wanders while trying to satiate his hunger.

Tokyo is indisputably trendy, with districts like Yoyogi-Uehara and Jiyugaoka filled with Instagrammable restaurants, but Inogashira is seldom to be found in these parts. It’s the rundown, quieter, even bland-looking areas whose stations the average Tokyoite would never go to on purpose that he frequents.

Similarly, the establishments Inogashira can be seen scarfing down steaming bowls of noodles or a well-arranged katsu-don set, have dusty interiors, faded awnings, and definitely no goal of being “stylish”. This is intentional, as The Solitary Gourmet touches upon something that Tokyoites know well, the best food is found in forgotten, cramped, out-of-the-way establishments [bonus points if it’s owned by someone over 65] outside of central Tokyo. For that you must head to Tokyo’s shitamachi.

Shitamachi are older and even decidedly unfashionable neighborhoods in and around Tokyo [not to be confused with boring] Inogashira walks through in search for his next meal.

Aside from the best food often being found in these areas, The Solitary Gourmet possibly chooses to capture Gorō in these areas because good food is synonymous with home or furusato [a word with connotations of an idyllic countryside home]. Watching Gorō devour each delicacy in a quaint shitamachi can replicate the feeling for Tokyo transplants who feel lonely even in a crowded city.

Far from feeling lonely on his solitary gastronomic adventures, Inogashira walks in these shitamachi districts like a bloodhound on the trail, often being deterred by chatty locals. A prime example being found in Episode 2 Season 1, where Gorō is craving a boiled fish teishoku set [as classic as classic gets in terms of Japanese food], but is finagled into joining a game of chess with a group of old men [which he leaves abruptly because hunger trumps almost any other emotion for him].

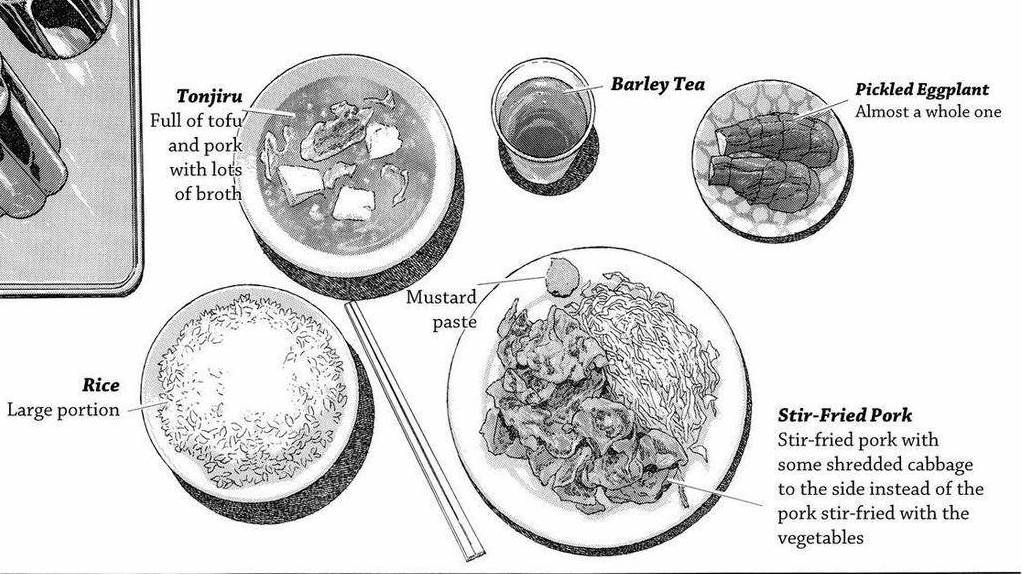

An example of a Teishoku set.

Leaving the locales behind, Gorō eats his meal in peace but thinks bout the people he’s met along the way. Gorō for someone called “solitary” sure has a lot of friendly interactions. For the show’s fans, and Tokyoites in particular, the city is a place they moved to for work or school or to achieve some sort of success, but it still lacks a sense of belonging that their hometown supplied.

In place of going to one’s actual furusato, Tokyoites visit shitamachi areas, or even easier just stream The Solitary Gourmet, an easy substitute for the feeling of being back home, minus the steep shinkansen ticket price. The Solitary Gourmet fulfills that yearning for many people to return to their nostalgia-tinged visions of “home”, and the irreplaceable dishes that are associated with it.

Goro enjoying Tonkatsu

TAKING YOUR TIME- THE EVERYDAY RITUAL OF A MEAL

Food is not just food. Especially in Japan, where it’s elevated to a status beyond substance but a coveted object, and bombarding the public from every angle. In 2006 according to the Washington Post, 35% to 40% of Japanese TV programming was food-centric, and within the realm of the gourmet manga genre there are hundreds of bestselling titles.

It’s no secret, Japan is a nation that takes cooking to god-tier status, through dedication and the pursuit of perfection. The Solitary Gourmet follows this same line of thinking where every dish is dissected to the smallest detail and every aspect of a meal symbolizes something bigger, whether it be a season, a region, a special occasion, or even a social group.

Gorō unintentionally walks viewers [especially foreign ones] through Japan’s unspoken ‘“food rules” which of course are broken, but earn you a side eye if breached: don’t eat while walking, frequent family-owned restaurants whenever possible, men are “allegedly” not supposed to eat sweets alone, accompany gyoza with oolong tea,and make sure you have a hearty helping of rice because without it he deems a meal incomplete. These opinions are shared by quite a few people in Japan, but of course everyone is an individual with their own take.

The manga mentions “food rules” often not explicitly stated by widely known, such as the belief that men shouldn’t eat sweets alone.

Goro doesn’t drink alcohol, but other than that has no limits in his gastronomical adventures.

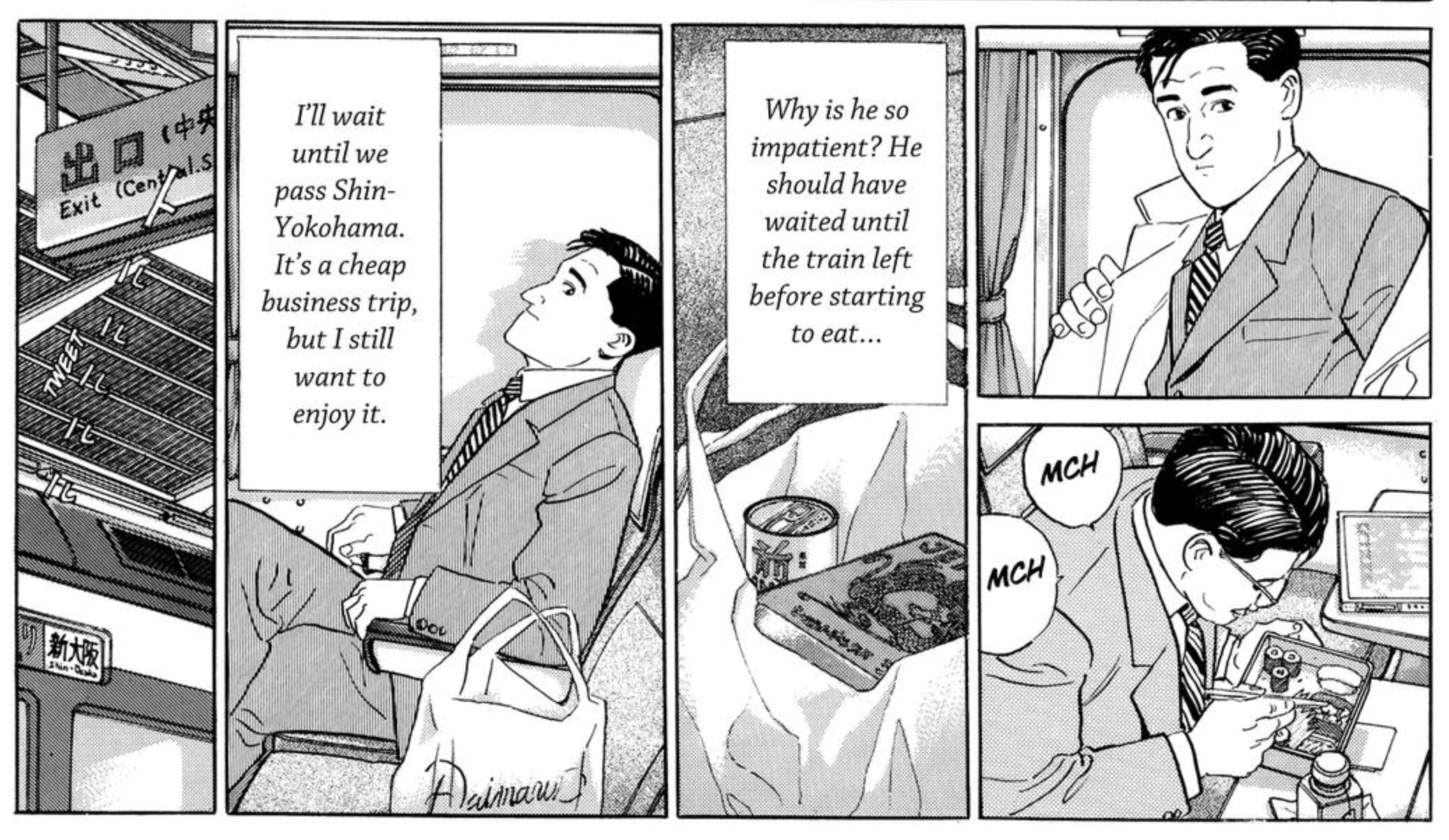

There are even more intricate rules depending on special circumstances, like in Chapter 6 of The Solitary Gourmet’s manga, when Gorō is on a shinkansen [bullet train] and orders a ekiben [travel size lunch boxes just for long train sides]. He becomes a bit outraged when another passenger starts eating his bento before the train even leaves the station. Or in Chapter 4 when Gorō is astonished that customers are drinking at an izakaya without ordering any food.

Gorō ’s reactions to eating habits that are easily passable in other countries articulates why The Solitary Gourmet is so special, it’s the little things mentioned that count and that are the most revealing about the way a society thinks and feels.

Goro really likes rice.

FOOD AND JAPANESE IDENTITY

The Solitary Gourmet is entertainment for sure, but also an unofficial insight into the intricacies of Japanese identity, and how food fits into this complexity. Food is one of the most important aspects of that.

Even amidst the mind-boggling assortment of new foreign food restaurants in Tokyo you can access, something that many Japanese people feel is an integral part of their cultural identity is eating foods determined to be “traditionally” Japanese.

For many Japanese people, there’s a clear idea of what true “Japanese cuisine” called washoku is. Whether that concept is an imagined idea defined to preserve a distinct sense of Japaneseness in a hyper-globalized world or an accurate description of dishes focusing on seafood, small side dishes, attention to seasonality, and an obligatory side order of rice and miso, is up for the individual to decide.

However, The Solitary Gourmet makes a clear choice to focus on foods that are deemed extremely “Japanese” by most in Japan, but pretty rare at Japanese restaurants abroad: ochazuke [rice porridge soup] or shogayaki [ginger grilled pork], revering them in a way other series haven't done as masterfully.

Just a quick skim of the Gourmet’s list of episodes shows that the vast majority of dishes lean towards being “traditionally Japanese” despite the availability of international grub. The best example of the Gourmet’s insistence on the glory of “real” Japanese food is in episode 2 season 5, where with a contented sigh after a belly-filling helping of sashimi Gorō says the dish makes him “glad to be Japanese”.

Yet the solitary gourmet doesn’t stray away from more controversial topics floating around Japanese society, most notably the not-so-accurate insistence that the nation is ethnically homogenous.

No matter how much conservative sections of government and the public insist, this just isn’t the case. Japan definitely has its share of immigrant populations [often from Southeast Asia or China], Zainichi communities [people who have Korean ancestry and historically have been discriminated against in Japanese society], and people of other marginalized socio-economic groups have contributed heavily to what is known as contemporary “Japanese” cuisine.

All of these groups are an integral piece of the puzzle of what makes Japan, Japan. These inter-cultural tensions and the dishes associated with each of these social groups are featured in The Solitary Gourmet’s adventures.

In Chapter 12, Gorō intervenes when a shop owner of a greasy spoon is mistreating a non-Japanese worker, while alluding to stereotypes that the worker's ethnicity makes him unintelligent and lazy. Or when Gorō visits what's known as “Little Brazil” the working class enclave of Oizumi, Gunma with a large Brazilian and Nikkei Brazilian populations [people of Brazilian-Japanese ancestry who grew up in Brazil or have family who did].

These Japanese-Brazilian communities are accepted as “Japanese” in society, often because of their Japanese lineage but frequently have different interpersonal norms.

As Gorō samples the beef feijoada and picanha of a local Nikkeijin-owned restaurant in Episode 2 Season 4, he notices the small differences of how even though some Nikkei Brazilians have fully of Japanese descent, Gorō feels like the behavior of boisterousness and comfortableness with affection give the community a distinctness he doesn’t see elsewhere in Japan, making him question the notion of what being “truly Japanese” means.

It’s these subtle commentaries on Japanese society, especially how food can represent race or class in Japan, that give The Solitary Gourmet an unexpected depth, behind it’s deceptively simple plot.

The Solitary Gourmet has earned legendary status in the gourmet genre domestically, but also legions of fans abroad who gravitate to the show and manga for little mind-numbing food-porn pleasure but, unintentionally become educated on how food affects Japanese ideas of place, ritual, and national identity.

The series is still ongoing, with 9 seasons thus far, spawning a cultural phenomenon of people going on “Gorō ’s Food Pilgrimage” by going full otaku mode and eating at every restaurant mentioned in the live-action or manga series, even dedicating entire youtube channels or Instagram accounts to the endeavor.

True fans even can skip the dirty work of deep diving to get all the restaurant details, by reading the “Solitary Gourmet Pilgrim Guide” an officially published restaurant booklet giving you the details on how to follow the footsteps of the unofficial patron saint of Japanese food appreciation, the humble salaryman Gorō Inogashira.

About the Author:

Words by Ora Margolis

![The Climber/Kokou No Hito [The Solitary Person]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1643371741134-EJ0TKJ2EIHBRV36YECJS/EkxulNPXUAILxuq.jpeg)