Tokyo Through The Ages - A Cinematic Perspective

Tokyo is loved for its hustle and bustle mixed with a hidden tranquillity down every street. The captivating, dreamlike city is known now for its bright-lights and business - but it hasn't always been like that.

Tokyo has done a lot of changing since earthquakes reduced it to rubble in 1923. Naturally, as the city is a hotbed for art and culture, these changes have been reflected in the films over the years. In this article, we will take a look at how different directors see Tokyo throughout different time periods, ending with a look into the future at Neo-Tokyo:

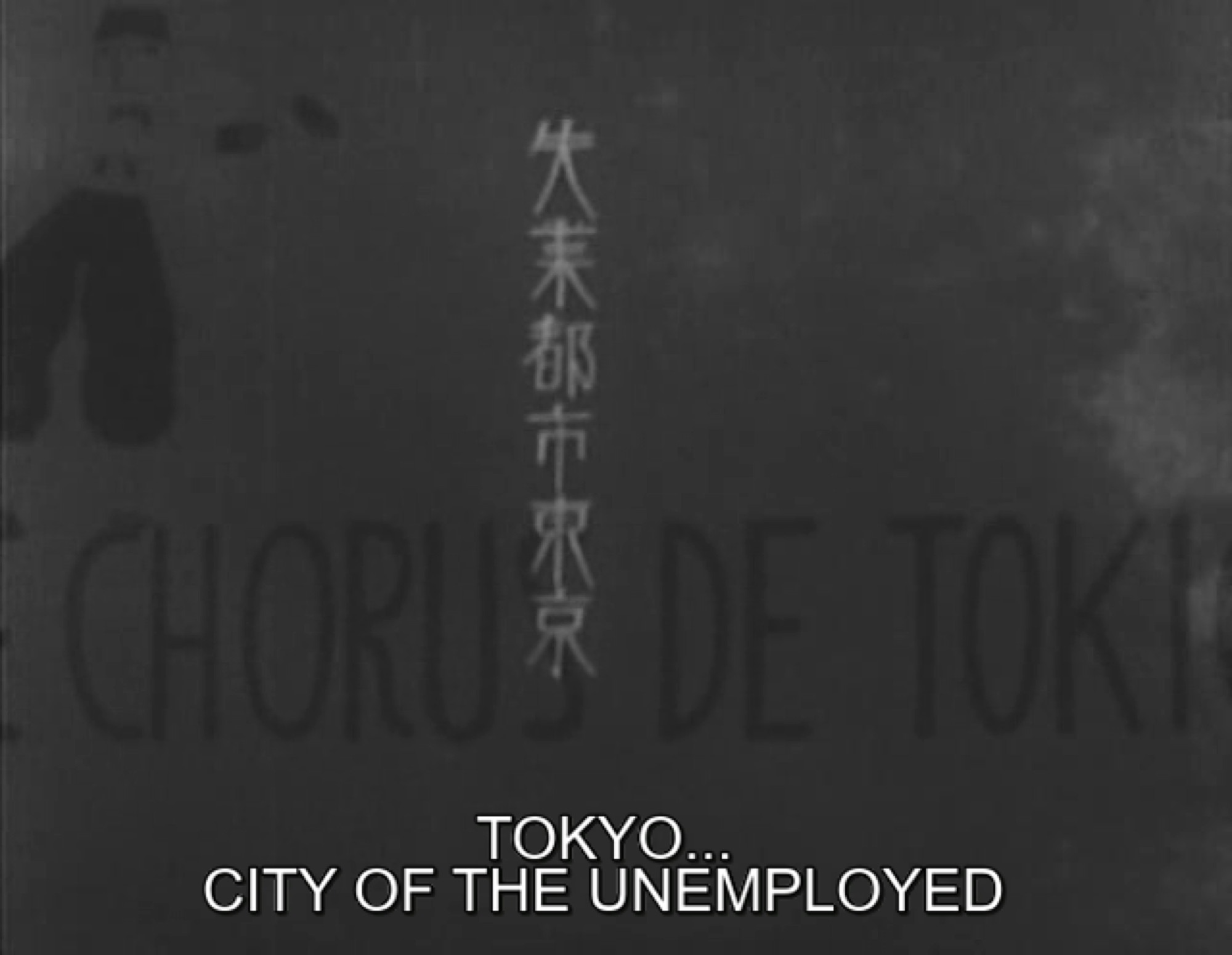

Tokyo Chorus, Yasujirō Ozu, 1931

We start this journey of the city with one of the first feature films set in Tokyo - Tokyo Chorus. This silent film tells the story of a rebuilt Tokyo in the midst of the great depression. It follows a man who, fired from his insurance job, must find another to supply for his family - unluckily for him, unemployment at this time was skyrocketing. As a result, Tokyo is portraying quite drearily. The first introduction to the city-centre is with a card stating “Tokyo...City of the unemployed”, followed by a shot of rubbish on the ground (and if you know the Japanese, you know no one dares to litter).

Tokyo is in a state of disrepair, frankly because the people are in mental disrepair too. The crowds outside the unemployment office only emphasise the vast, empty streets.

The architecture is seen to be less traditional, and more western - large, neo-classical and utilitarian office buildings fill the streets. This is mostly due to the earthquake mentioned above. Not only did it destroy many traditional buildings, but it also encouraged the construction of new buildings that could withstand another one. As a result, they turned to western architecture. Yasujirō Ozu, the director, and one with an appreciation for the traditional sees this shift away from it as a poor choice. The empty streets are representing the lack of national pride for cultural heritage in a Tokyo that is, for the first time, attempting to establish and attract international business.

Although the bleak outlook, Ozu gives us a hopeful ending. The protagonist is offered a job in a faraway prefecture. His wife smiles, “I’m sure we can return to Tokyo someday”. Ozu saw Tokyo at the time as a place that still needed to develop, keeping in mind where it came from. This dynamic is interestingly inverted in one of his later films - Tokyo Story, but we’ll get to that in a minute.

Stray Dog, Akira Kurosawa, 1949

What makes Stray Dog interesting on this list is that it is the first post-WW2 film. It’s one of Akira Kurosawa’s rare detective-noir films. A rookie detective who is looking to prove himself in the force has his gun pickpocketed. Humiliated, he has to track down his stolen gun and foil the secret Tokyo arms market.

It sees the cop explore the slums of Tokyo in the wreckage the war left. The streets are in tattered ruin, but the damage wasn’t just physical. Kurosawa shows the effects of war extends to people of the city too. The title Stray Dogs refers to these people. They are strays out of a home and must scavenge the streets for whatever they can find to survive - be that food, blankets, or a gun.

In this film, Kurosawa shows the brutal effects that the war had on Tokyo. This makes it all the more impressive as we go further down the timeline, and see how the city has recovered.

Tokyo Story, Yasujirō Ozu, 1953

Tokyo Story is what many consider to be Ozu’s best film. It’s about an elderly couple from a small town visiting their grown children in Tokyo. They become quite quickly overwhelmed by the sounds and speed of the big city. Not to mention that their children are too busy to spend time with them.

This film takes an interesting perspective of the traditional entering into a modern world. Ozu wants the audience to consider Tokyo and its shortcomings from an outsider’s angle. He suggests that in the rush of the city, the youth are forgetting about the old.

Being a post-war film, a lot about Tokyo has changed. Firstly, the extensive firebombings carried out on Tokyo destroyed many traditional and contemporary buildings. Thus the process of rebuilding began again. This led to all kinds of modernities like skyscrapers, radio-towers and industrial chimneys gracing the skyline.

However post-war Tokyo also carried a different attitude. One of progress. The classic Japanese “work hard and don’t stop” attitude is present in the younger generation, who find little time for their visiting parents.

Although, Ozu shows that despite all the changes Tokyo is undergoing, what makes the city special will remain - the people. This is seen through the interactions between the grandmother and grandson. In a very cute scene, he shows genuine curiosity and the wonder in collecting and exploring the grass.

Ozu is showing the children will always develop their natural tendencies for adventure, so Tokyo will always be in touch with its true traditions. He shows that Tokyo is built off hard work, hope, but most importantly curiosity.

Tokyo Drifter, Seijun Suzuki,

1966

In Tokyo Drifter, the changes in Tokyo are not to the city, but its style.

As Tokyo further westernised so did the fashion and the past-times. Men get dressed in bright suits and take part in American past-times. Jazz clubs, bowling alleys and arcades are seen as a common hangout spot.

It’s fitting this is the first colour film I mention in this article because colour is something that defines Tokyo Drifter. The bright clothing and colour palette of the film is very representative of the peak of Japan’s economic miracle - the vivid colours like a blooming flower. Following on from Tokyo Story, it’s in this time period that Tokyo developed into the bright and fast-paced city that it’s known as today.

During the 60s, not only did the people start dressing in a new vibrant style, but the city took on a new life determined by the activities of the people. The streets were filled with entertainment spots as Tokyoites had more disposable income. As a result, the 60s marked a period of fun and hope for the city.

Tokyo Ga, Wim Wenders, 1985

Tokyo Ga is a documentary about Wim Wenders’ trip to Tokyo. His monotone voice and complex images take us on a journey to explore the city he had admired from Ozu films.

What makes this film different from the others featured here, is that Wim Wenders, is not Japanese, but German. In that, he sees a unique vision of Tokyo. He is an outsider making sense of the city, and as a result, Tokyo is characterised by the one constant found in every city - the people. When navigating the train station, while he has plenty of shots of the technology and the trains themselves, he stays silent until he tells us about the mother and the child that has no energy to go on.

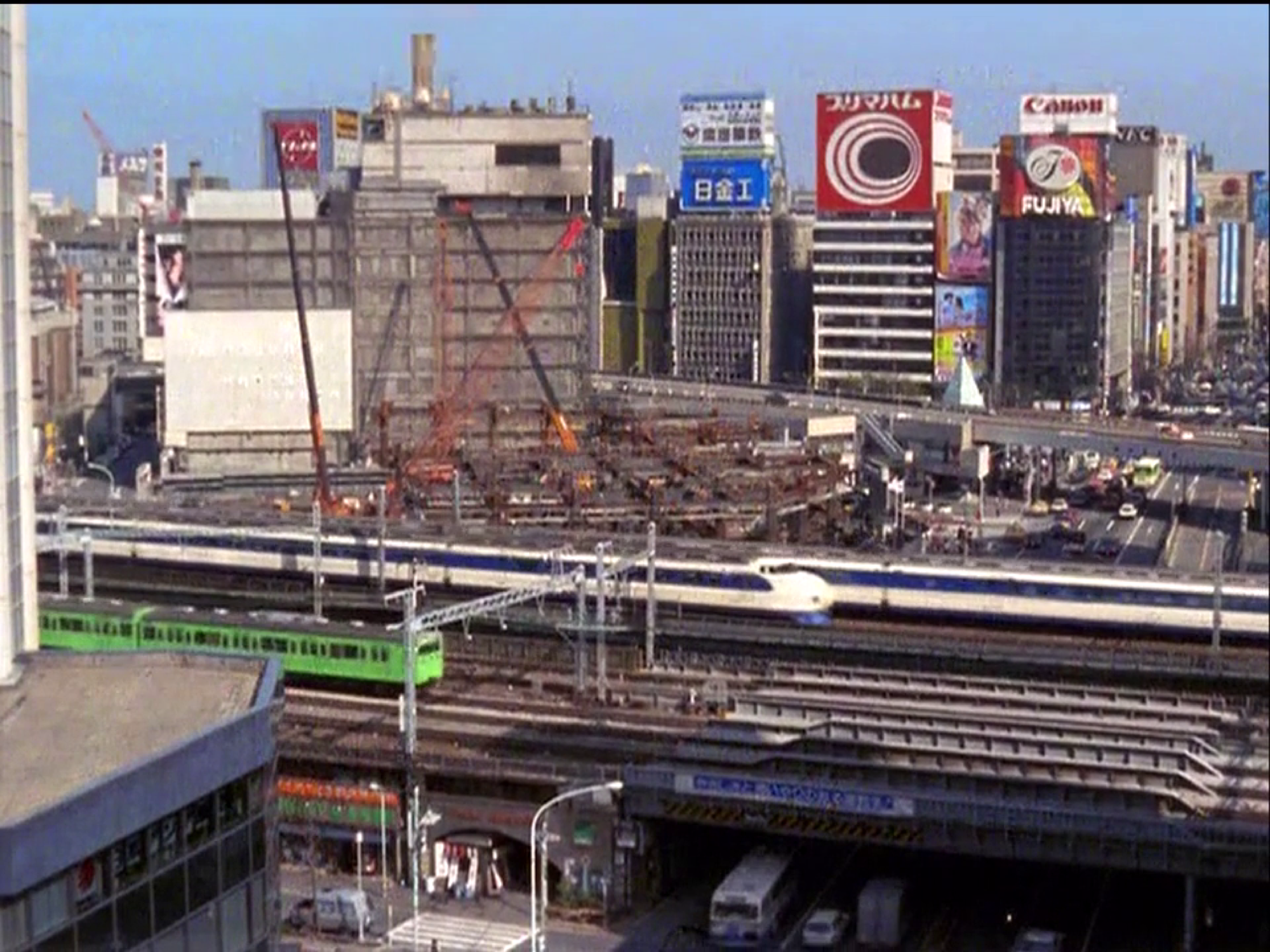

However, he also takes note of the evolving cityscape and technology. As an outsider, he sees a conflict between the new developments and the peaceful centuries-old traditions. Although in this rift there is something to connect it all - trains. Much like his idol Ozu, Wenders admires trains, and their ability to link the old and the new, the forest and the city, the traditions with technology.

In Tokyo Ga, Tokyo is seen to be more vibrant and optimistic as ever. It shows the city at the peak of their economic fortunes and technological boom. It is a great look at the liveliness of the city, and the people within. The city is portrayed as a large sprawling labyrinth, however, is familiar thanks to the kindly citizens, and the exhilarating energy of the streets

Enter the Void, Gaspar Noé, 2009

Through Stray Dog, we’ve had a brief look at the underbelly of Tokyo. Enter the Void revisits it 60 years later to radical change. The drug trade is the new king of seedy side of the city, and this film takes a revealing look at the people that feed off it. It tells the trippy story of a gaijin and his sister trying to make a living any way they can. However where this film shines is its hypnotic and absorbing visual style.

“If these walls could talk” as the maxim goes; well Noé shows us exactly what they would say. Psychedelic strip clubs, dark alleyways and pulsing lights - we are taken on a journey into the crazy Tokyo nightlife. Every dark, unexplored corner is lit up by Noé to reveal a city run on drugs, sex and dirty money.

The choice of shots shows this so well. There are three types that characterise this film: bird’s eye view, first-person POV, and a close over the shoulder shot. These three shot-types make for an extremely personal tale - it puts us right in the middle of the action, and reveals what is usually drowned out by the bass-heavy club music.

It shows us the beginning of the economic struggle in Tokyo. The city is facing its biggest fall in decades, all the while inequality is rising and hope is falling. Despite an increasingly connected world, people are feeling more estranged than before. As a result, Enter the Void sees a change in the activities of Tokyoites. They attempt to mask torment with the elicit. The two main characters are perfect examples of pained individuals who just want to escape it all in the big city - only to find how unforgiving it is.

Shoplifters, Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2018

Winning the 2018 Palme D’or (one of the highest cinematic achievements), this devastating personal tale became celebrated as one of the greatest films of this decade. It follows a poor rag-tag assembly of a family as they try to survive the harsh modernities of Tokyo. However this family is not bound by blood, but out of necessity - survival in packs.

It’s in this film that the fast moving innovation and economy is being seen as a bad thing, as some people are getting left behind. It beautifully shows the struggles of low-income life in a big, expensive, business hub. Tokyo is portrayed as a grand, and beautiful city, but also an unequal one.

Loud streets are countered by the silent maze of pathways the family slinks down. This is to show their struggling existence is overlooked, and the bright lights can take away or even mask the inequality at the heart of the city.

Akira, Katsuhiro Otomo, 1988

Now that we have examined the portrayal of Tokyo through many different time periods, we turn to the future. The prime example for this has to be from the iconic Akira. Although Neo-Tokyo is set in 2019, it's no-doubt a look into the dystopian future that could await us. In the film, Katsuhiro Otomo examines a Tokyo rebuilt 31 years after WW3.

Much like Japan’s post-war miracle following the devastation of WW2, Otomo envisions a similar thing happening after the hypothetical WW3. While ravaged by inequality and run by street gangs, Tokyo has developed economically, with huge skyscrapers looming ominously over the brightly lit city. Holograms and highrises adorn every shady street corner of the sprawling city.

However, these bright lights just help to illuminate the rampant crime and police brutality. Unlike the previous hopeful views of Tokyo’s economic and technological growth, Otomo shows a dark future of inequality that comes with rapid growth (like a grim-future version of what Shoplifters is showing).

Conclusion

It's easy to see the changes in Tokyo superficially. Changing architecture, more technology, there is a clear difference between Tokyo in the ‘30s and now. However, if you look a bit deeper, you’ll discover an important underlying theme in many films about Tokyo - the people. The people are just as crucial to the city as anything else. They are what makes the city special. The attitude of the people is reflected in the city itself - hope filling the streets with colour, and pessimism, emptiness and anonymity.

Tokyo is only as good as its people, and despite its turbulent past, its inhabitants have stayed strong. What characterises Tokyo is not the bright lights, the busy streets, and the fast-moving culture. Instead, it is the people behind the lights, the people that make the street busy, and the people who work tirelessly to innovate and develop the culture.

About the author:

Living in Adelaide, Australia, Jack Duxbury is an expert in Romanian, Iranian, and Czechoslovak New Wave cinema. In his spare time, he writes and directs short films and advertisements. He enjoys film theory and the philosophy of cinema.