Your Favourite Designers’ Favourite Designer: sabukaru meets Aitor Throup

In an industry driven by novelty, few figures in fashion and design embody genuine innovation quite like Aitor Throup. Enigmatic and expressive, Throup occupies a rare space, both on the knife’s edge of creativity and deeply embedded within technicality. His work has long transcended the conventions of fashion, existing instead in the charged intersection between design, performance, and sculpture.

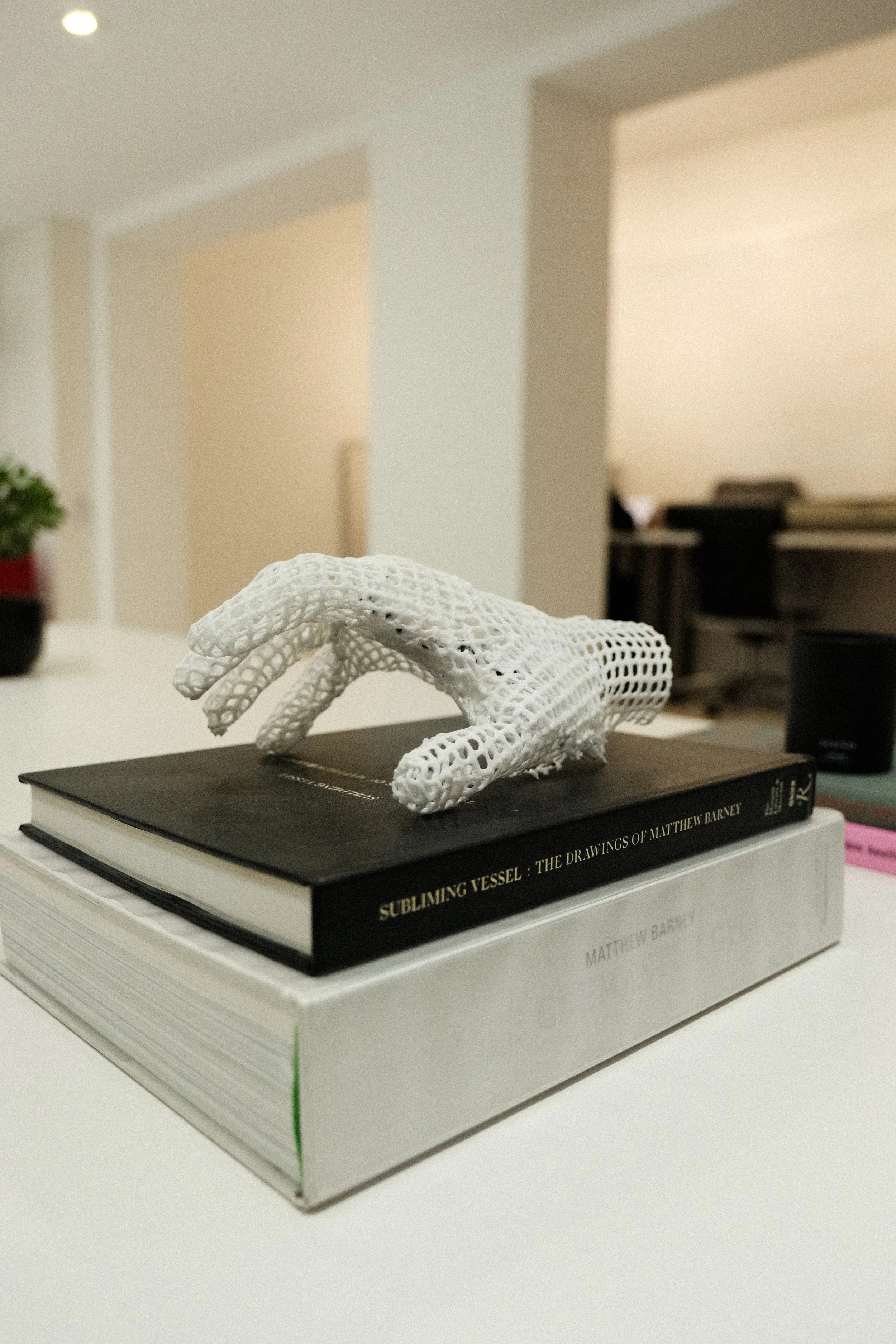

To encounter a Throup piece is to experience a world built from anatomy, narrative, and meticulous construction, each garment or showcase a study in form, motion, and identity. With this being said, it gives us immense pleasure to have the sabaukaru London team visit him and his team down in his studio ahead of his upcoming exhibitions titled ‘FROM THE MOOR’, to get an exclusive insight into his design process, his humble beginnings, and his exciting future.

Born in Buenos Aires and raised in Burnley, England, Throup’s creative sensibility was shaped by a collision of cultures. His fascination with identity and belonging, a recurring theme in his work, can be traced to this dual heritage, as well as to his early engagement with subcultural dress, British football culture, and figurative drawing.

Throup’s cult-like following is not one born of hype, but of deep creative respect. Since his early collections, from When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods (2006), which fused sportswear archetypes with mythological storytelling, to his tenure as creative director for G-Star RAW and his own conceptual label New Object Research. Throup's approach dismantles the idea of fashion as surface, insisting instead on meaning, movement, and transformation.

Where others chase trends, Throup challenges the very framework that produces them. His projects, whether clothing, installations, or performance-based works, are moments of total world-building; where art, engineering, and philosophy converge. He stands as a reminder that fashion can be more than commerce or costume: it can be an evolving system of ideas.

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us today. Can you kick it off and tell us who you are, and a brief introduction to what you do?

My name's Aitor Throup, and I'm somewhere between a conceptual designer. A fine artist and yeah, there’s fashion in there somewhere. And somehow.

What impact has growing up in Burnley had on you as a creative?

Growing up in Burnley I would say is the primary reason I became a designer, and there's multiple reasons for that. One is primarily that it really introduced me to an experiential relationship with football. Before that, growing up in Buenos Aires, it was too dangerous to go to a football match. In Madrid it was too expensive. We had no money, and then when we landed in Burnley, even though we still had no money, you actually didn't need much money to go and watch the football. It was my next door neighbour's dad that used to take us on.

For me, it was just like this incredible experience. It planted this seed of this culture and this subculture where on one side you had football, and on the other side movement and the body. I'd always had an interest in movement, maybe because I've always drawn since being a baby and mum was training to be a doctor when we were in Argentina, so my childhood was surrounded by anatomical books and I was obsessed with that. So somehow my drawings and all these anatomical medical references resulted in this obsession with movement, and so football allowed me to analyse movement, close up in a sort of environment where the variables were relatively contained. They were similar sorts of moves.

On one side there was an obsession with the actual football being played, but on the other side, there was this new interest being implanted in my brain about the subculture of football fans and football uniformity. Like these football casuals, the football hooligans and in particular, those brands that were making such incredibly beautiful and incredibly progressive products like C.P. Company and Stone Island. All of that comes from Burnley, it was somehow a platform of inspiration for me.

If it wasn't for Burnley and Burnley Football Club, I literally wouldn't have become a designer, I don't think.

You’ve often described your work as a form of storytelling through design. How has that philosophy evolved from your early projects to your most recent work at A.T. Studio?

I think storytelling has always been a part of my work because if there is no story to tell, there's almost no reason to do any work. I think it's in the story where you find meaning, and I would say how it's evolved through the years is that I've been able to, in many ways, understand the premise that connects all the stories that I've told.

My storytelling became more focused at the beginning, they were sort of hermetically sealed, conceptual frameworks of specific stories and narratives that were expressing some fundamental truth that I was trying to get to. Then over the years, it's almost like a film director doing all these stories and it's only in retrospect when I look back through all those stories that I can kind of see a pattern emerge of a broader story being told. And that's probably the primary reason why I've taken the last eight years or so relatively away from the industry doing smaller projects, figuring out the broader premise I didn't want to get into the cycle of. I'd already fought the temptation to enter an industry by its own norms and rules and formats and cycles.

I already knew that didn't work for me. I never wanted to do seasons, I never wanted to do conventional catwalks, but I figured I was in danger of, in a way, going into my own cycle, into my own repetitive thing and creating another conceptual story with another narrative. I need to get to the bottom of what's the broader thing that I'm trying to get to. It was a very intensive process to figure that out.

So I think that's the main way my storytelling has progressed is in becoming more focused about what it is you're trying to say. The second way it's progressed - I always look at storytelling from two sides. One as an artist and one as a designer. As an artist, you're sort of proposing a narrative and a story. It's like a conversation, you know? But the designer part of me actually comes in and concludes that story. So it allows you to contemplate, I think, as a viewer of the story. Come to a conclusion. Which I think is really important. So through time as an artist, I've tried to become more intentional with the story and as a designer, I've tried to become more capable with more disciplines to tell a more specific conclusion of that story, I think that's my ultimate objective.

Your career spans across fashion, art, music, and product design. Do you see these practices as seperate ‘lanes’, or part of one continuous discipline?

I see them as different lanes. There's a craft attached to all of them, and I'm very respectful of that craft. They all intertwine in helping to convey a singular story though. When I started learning my first craft, drawing, I taught myself from being a baby and through that, I got interested in style and clothing and these kinds of brands that came from Massimo Osti. That was my first obsession.

I then got interested in clothing and style and Massimo, so obviously my drawings and my characters start becoming more more detailed, and all of a sudden my character's got a garment that's got pockets and all of a sudden I've got an opinion on that style of clothing, or I start to think about making those types of garments. But my drawing craft doesn't allow me to create a jacket.

So then, I thought, “what do I need to learn to make this into a jacket?”. So you go and learn and then all of a sudden you're in fashion school, but you're not there to learn about fashion. You're just there to make this bloody jacket. Then, you learn how to make a jacket and you go, “no, that’s not quite right. It needs to move in a different way.” And so you teach yourself pattern cutting in a different way. Then you end up with a jacket that's really interesting, and you take a crappy photo of it and you're like, “that's not quite right.” So you go deep into photography and then you take a decent photo of it.

You're learning these individual crafts. It's gone from drawing to design, to pattern cutting, to photography. Inevitably you get to graphic design. Each of these crafts are amazing fields to immerse yourself in. And I've just continued through a natural sort of expansion of how to optimize the story that I'm telling through these designs. And it's obviously led me to be beyond photography and graphics, into videography, into music, into sculpture, spatial design. They're all just secondary to the story that was at the nucleus. That’s why this industry is multidisciplinary, because it has to be.

From When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods to New Object Research, there’s always been a strong conceptual foundation. What drives you to prioritize narrative and concept over pure commercial output?

Well, for me, I became interested in clothing design because of the story. As an artist I realized that first of all, I'm more interested in art than I am in design. But I realized that being good at design will help me create objects that allow the artwork to interact with human beings more so than just a pure artwork.

So I think that the intersection of art and design has a very functional nature to it. You can easily say that I'm more interested in storytelling and narrative than I am in commercial expression. 'cause for sure, I could have many years ago made something commercial. Created a brand with t-shirts, hoodies, etc. It's very commercial to do that, and I genuinely like it. But I don't think I'd be able to do that. If there's no cohesive story or reason, I just feel like I'd be polluting the world. It'd just be more stuff. Who needs that?

I think there's a real responsibility with creative energy. If you're gonna use your creative energy to put something into the world, then you better have value, better have meaning and reason.

Artists often share feelings of doubt - ‘imposter syndrome’. With the conceptually rich outputs you create, is there ever any fear that things may be misunderstood? And if so, how in ways can this be used as a driving force for you to dig deeper?

With my work there are so many layers to it that it's more likely than not that somebody will not understand what it is. But my theory is I don't need people to understand what something is. There's this theory that when a human being sees a figurative piece like a sculpture, we have a psychological reaction or an emotional reaction to it. We see ourselves in this piece, right? So when we see a painting or a sculpture, it's a sort of reflection of us. And, so we create a psychological relationship with it. That’s a big part of the power of art and in particular figurative art.

I always talk about working from the inside out, working from a reason and eventually manifesting into an object. That could be a painting, a sculpture, a piece of music. My theory is that when we interact with pieces that have been built from the inside out, so with integrity, with reason, similar to, but on a much deeper level, to when we interact with a figurative piece, like a sculpture of the human body, we recognize that that thing, that entity was created from the inside out in a, in a sense we're interacting with ourselves 'cause we're seeing or hearing experiencing something that has a soul.

And the fact that it came from the inside out, from a reason, from a concept, and that created processes that eventually manifested something final, like an object or a piece of music. You gauge all these layers in one. Understanding the concept behind it is secondary to the fact that the flow of energy was outward. How and why it was outward is secondary to it.

Many consider you a “designer’s designer” — admired for innovation rather than mass reach. How do you feel about that statement?

I suppose it's understandable that people might consider me a purist in the world of design and in the world of art and in particular, the intersection of art and design. in particular when that crosses over into fashion. But I just want to be very clear about that for me. I believe the truth for any artist who's really got something valid to say is that success really comes from your message being conveyed and the message landing. I'm a strong believer that art is very clearly communication.

It doesn't necessarily need established linguistic systems, it's whatever you need to do and create in order to convey a message. The message might not be a linear one, it might be an emotional message. So for me, how wide reaching it is, is important. It’s not like I'm happy to just be a niche designer in the corner, for the sake of being a purist. It’s not because I don't like what other brands are doing. It isn't that at all. It's that I deliver at a pace that is, and at a volume that is consistent with the potential and the clarity of the message. You know? So when your message can only be conveyed in a very narrow way, you can have a very narrow audience.

My natural impulse is to go broader and wider always, to become a holistic message rather than an individual little message. So, it's about the balance of retaining the purity and the clarity, but reaching more people because I believe my message is valid and valuable - meaningful. So of course, I want it to reach more people.

Your design process often begins with anatomy and movement studies rather than traditional sketches. Could you walk us through how this might change your approach to working with different fabrics?

Starting my learning process from the work of Massimo, materials became a big part of my process and actually my first ever collection, Mongolia, when I was still a student at Manchester Metropolitan. It was back then that the original Mongolia collection was so full of different fabric experimentations, different textures and different ways to articulate different areas of garments, etc. So from the very beginning, I had a deep fascination with materials. But as my practice increased, there was a section of the practice which was really interested in ergonomics and anatomy.

So we need to have an understanding of how the body moves, which obviously connects back to ergonomics. But I also mean product anatomy, not just human, so trying to create systems that give an object, a garment, a clear anatomical system so that you start to recognize areas that have certain features in order to do certain things that relate to the body.

For instance, I became very interested in the idea of a sleeve not finishing at the wrist, but instead finishing at the fingers or with trousers not finishing at the ankle, but instead, finishing at the toes and how to build in gloves and shoes and shoe covers into these archetypal garments. So in many ways an anatomical approach to product design and garment design really depends on materials; different materials in different parts of the body in order to do different functions, as well as sculpture materials that allowed me to cast the body in different forms.

You’ve often used mannequins, sculptures, and even puppets to showcase your work. How do you decide what medium best communicates a project?

The natural format for me to exhibit my work will always default to a sculpture. When I imagine an outfit completed, I would much rather imagine it on a sculpture suspended in a beautiful gallery. From the beginning when I started imagining my work, I always imagined it like this. And I think it's a very powerful and interesting thing because I had no aspiration to visualize my work on models walking up and down a catwalk, with an audience just sitting there. Maybe it's because as an audience, you can’t really experience the clothing.

As someone who's genuinely interested in a product, I'm a product geek. I'm trying to create these objects that satisfy my growing need for things like interesting details or whatever. So from that perspective, I don't get much satisfaction from being sat in my mind's eye being sat somewhere and these people walking up and down a catwalk. I just think it's not that interesting. But when I think of this garment and this outfit, or these many outfits being suspended in a space as somebody genuinely interested in the product and story, I just love the idea of walking around it, taking my time, exploring it, looking at it from different angles.

I really love that it subverts the psychology of a fashion exhibition. Sat watching, you're just observing. There's a sort of power over the audience in catwalks. You're watching this show that's unfolding however it wants, and you're not in control. Whereas you go into an art gallery, the work is passive and you are active and you can choose where and how you look at this thing. To me, that's much more interesting. When you have that freedom, it's more inspiring in my opinion, because you can connect to your imagination. You can start to imagine its potential rather than its conclusion.

Collaboration seems central to your practice, whether with musicians, artists, or brands. Today, collaborations feel so transactional, so what’s your approach to ensure that yours feel genuinely authentic?

The beginning of the conversation of a collaboration has to be about the story, it has to be. What is it we're trying to say? For me, it's so easy to work with a brand, musician or someone that I respect. I don't even need to have an understanding of them. I just need to have an interest in them. Because the first part of the task is to tie your hands behind your back and hold any impulses back until you learn. And obviously you are always gonna have your natural instincts and your impulses, but you're trying to hold back until you learn enough about the story, about their reason, about who they are as a brand, as a musician, as whatever. Then use that in the same way that I use my own inspiration. I start to listen to that. I start to listen to what it needs, how I can service that story. The work grows organically.

With New Object Research, you created a kind of ongoing laboratory of design rather than a conventional label. What did you want to challenge about how fashion brands operate?

Well, to be honest with you, I never felt like I wanted to challenge the industry necessarily. It's not like I looked at the industry and I thought I really want to challenge this, and show people an alternative. Not really. It was more like those conventions just don't work for me, and then they don't let this particular story be expressed at its potential.

For me, one thing that was very important was to create a platform that prioritized the optimization of an idea, and I saw it as three layers essentially: when is a design good enough? Is this product interesting? Is this product at the highest level of that? The reason why I started New Object Research was because the third level I felt I hadn't achieved, which was product excellence. I really wanted to get to a point where it was an amazing concept, amazing design idea, and has now been executed at the highest level. I used New Object Research in particular in 2012 and 2013, to go back to my archive and elevate.

There is a fourth layer, which is what I'm really interested in now. It's being able to sustain those previous three layers with a commercial aspect to it. A sustainable business model and reach. Now, as I'm brand building and really preparing to launch ready to wear, that's a big part of the aspect as well for me.

You’ve described your studio as “multi-disciplinary”. Do you see the future of design heading toward this hybrid practice, where boundaries between fashion, art, and design dissolve?

I always talk about the two ways of working from the outside in, from the inside out. Having a multidisciplinary space is very, very valuable if you are actually working from the inside out, because sometimes you just need different tools to express the message that you're trying to express. What I have seen sometimes recently is there are multidisciplinary expressions, but in a synthetic way - from the outside in. And I feel like in today's day and age, we're at the intersection or the crossroads between a shifting sense of value.

What is value? Currently there's a confusing state around what is valuable. I'm looking at a fashion show and it has different disciplines and components built into it that are unexpected, and so that's valuable because the designer is thinking broadly. But, I think that’s beginning to wear thin. The joke is imploding in on itself. It's now sometimes a gimmick, where designers and brands are trying to create viral moments essentially.

These viral moments a lot of the time are, in nature, multidisciplinary. It's ‘how can we involve a different discipline to create something viral?’ Whereas I think the future of where we're going is that multiple disciplines can be employed to really tell something holistic and very deeply meaningful.

Looking back at your expansive career, what do you think is the connective tissue, the through-line, that links all of your projects, from your earliest student work to today?

There's one fundamental thing that links all of my work, which is this fascination with the human body. You know, the fact that my work always starts with the body as opposed to with standardized blocks, standardized solutions, and conventional ways of constructing a garment. I'm more interested in looking at the body than looking at other garments that have existed before. If you first look at the body in your design process, there's so much information, so much more new data that you can extract from that, that can result in not just newness for newness sakes, but actually something more valid; whether it's more functionally valid or just more interesting.

I'm really interested in anatomical design. I think that's a thread throughout my work, but I think what's really important there is that when you create a new product anatomy, by working with human anatomy, you inspire people with the conventions that we live with. There are new solutions. We can break a paradigm. And I think that's inspiring because that can apply to any walk of life. Whether you are a designer or an accountant, you see something that has its own system, develops its own paradigm. It inspires you to think in the same way. It liberates you. All of a sudden, the cage that you're in doesn't feel as constrained. There is an escape, if you one day choose it.

Also increasingly through time I realized that on a deeper, more philosophical level, the thing that I'm most interested in is this idea of how the human condition is essentially about our natural expression being duality, which creates a lot of problems. I think about how our mission is to come to non-duality. Essentially from chaos to balance. I became very aware of this in my early work, exploring racism, for instance. That was the first time that I was looking at a very visceral expression of duality, in the way that it expresses itself in a toxic way in our lives. So you’ve got black versus white, white versus other, etc. My Argentinian-ness versus my British-ness. And then later on, after years of sort of working with different narratives around this sort of duality, I became more and more interested in it from a physical duality to a mental duality, and in particular hemispheric lateralization of left and right brain activity.

A lot of my drawing practice became grounded on this. I created a system and numerical logic based daily drawing system where every drawing has a number. It's a very left brain practice. And within that left brain practice, I can express myself creatively, imaginatively with my right brain. And so there's a balance of left and right brain activity, and that's non-duality.

Where I am now is connecting that with the spiritual, and essentially like non-dual expressions, a spiritual being, which is most clearly expressed in Chinese philosophy with Yin and Yang, essentially like masculine and feminine energies within all of us. We all have a masculine energy that's essentially a container for life, but we also have a need to express ourselves creatively, which is our feminine energy. So, somehow, from black versus white to left brain versus right brain to Yin versus Yang, it's about turning the versus into a unison - into harmony.

It's ultimately a paradox, you know. The deepest truth of life, I think, lies in paradox. Both things express themselves at the same time.

To round things off, what’s next for you?

We are deep in work now with two new collaborations. One of them we've already announced is Umbro, which will be coming out next year, which I'm very excited about. There's another really exciting collaboration that we haven't announced yet. Maybe another one as well, so potentially three, at least in the next year.

Then in the middle of all that, we will announce the ready to wear brand, which is the holistic coming together of the vision that I've been explaining. It’s a sort of moment that I've been working towards for a long time and I finally feel very ready and confident that it's the right time.

Interview and words by Joe Goodwin

Edit by MANDO

Grab your tickets here for Aitor Throup’s upcoming exhibitions, titled FROM THE MOOR