Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: The Birth of a Legend

A thousand years after a nuclear apocalypse has left the world in devastation. Nausicaä, a 16-year-old princess flies over a vast toxic jungle. Known locally as the Sea of Corruption, the jungle grows exponentially. Impossibly dense, it is protected by giant trilobite-like armoured creatures who rampages outward whenever humans attack, dispersing spores to catalyse its spread.

Split into states positioned along a desert region known as the Periphery, the last remaining human colonies exist under constant threat from the jungle. Owing their allegiance to the Kingdom of Torumekia [Tolmekia in the film], a militaristic empire governed by an immortal Vai Emperor, the states live autonomously due to an age-old treaty. Yet, when the Torumekians invade, in search of a weapon to put an end to the hostile jungle, the treaty is broken, bringing the world into near-cataclysmic conflict. This is Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, manga-turned-anime by master filmmaker, Hayao Miyazaki.

Published between 1982 and 1994 through the Japanese anime and entertainment magazine, Animage, Nausicaä is lauded for its world-building, complex characters, and relevant worldly conflicts mimicking the struggles humanity faces today. Laying the foundations of Miyazaki’s hallmark slow style, his recurrent themes of environmentalism, politics and warfare, it built the tonal and visual basis for each of his subsequent anime masterpieces, and achieving an epic sweep rarely seen in action manga. Yet, while depicting a story strewn with deep, philosophical ruminations, Miyazaki manages to hone Nausicaa back to its most fundamental human qualities – morality, empathy, survival – focusing on the moments in between the action. This article delves not only into the themes of the groundbreaking anime, but also the legendary process leading to its creation, and how it propelled the emergence of Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli which would go on to create some of the most impactful anime of all time.

Miyazaki Before Nausicaä

Before the formation of Ghibli, Miyazaki had already enjoyed an extensive career at in animation, storyboarding films such as Doggie March [1963] and Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon [1965], and working tirelessly under the mentorship of Yasuo Ōtsuka, one of Japan’s foremost animators.

Miyazaki and Ōtsuka at A Production, around 1971 by Minami Masatoki via @studiotstella

Through Ōtsuka, Miyazaki was introduced to his later long-time producing partner, the late Isao Takahata, who took note of Miyazaki’s talent, bringing him on to work on Wolf Boy Ken [1963], the first anime series produced by Toei Animation, and the film - The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun [1968]. Takahata directed both projects, with Miyazaki designing the storyboards, the style of which would prove synonymous with their later works at Ghibli.

Friendly Rivals, Miyazaki and Takahata, During an Interview in 1990 via Kyodo News

Collaborating on numerous series such as Heidi, Girl of the Alps [1974] and Lupin the Third Part I [1971], Takahata was able to land many of Miyazaki’s early opportunities in animation, and they later would go on to be frequent collaborators. Winning Miyazaki his first directorial gig, Nippon’s Future Boy Conan [1978], which Takahata worked on as an uncredited director and storyboard artist.

In 1979, however, after leaving Takahata’s series, Anne of the Green Gables, Miyazaki’s solo career began to pick up steam. He moved to Telecom Animation to direct his first feature film, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro in 1979. While a box-office flop, Cagliostro had a global impact, inspiring the Disney Renaissance period of the late 80s to 90s, in which the American animation giant saw a return to form, producing critically and commercially successful animated films.

Later voted “the best anime in history” by readers of Animage in 2001, Cagliostro proved that Miyazaki wasn’t just some salaried animator, but a director with a vision of his own. Around the same time, the aforementioned anime magazine, Animage, was still in its infancy, with publisher Tokuma Shoten hungry for content from contemporary animators and mangakas. Seeing Miyazaki’s rise to prominence, they approached him to write a series of articles for the editorial staff. Animage editor, Toshio Suzuki, was already acquainted with Miyazaki after he and Takahata refused to give an interview for the inaugural issue of the magazine back in 1978. This time, however, their conversations were more fruitful.

“Toshio Suzuki” by Eddie Shannon Licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0

During a series of meetings with Suzuki and co-editor, Osamu Kameyama, the idea of developing an anime based on Miyazaki’s unproduced work began to germinate. “If you have a good idea, bring it to me” Suzuki recalls Yasuyoshi Tokuma, founder of Animage stating, in his memoir Mixing Work with Pleasure: My Life at Studio Ghibli [2018]. And so, that’s what Suzuki did. Plucking ideas from Miyazaki's garden of ideas, and pitching them to Tokuma.

“Early Concept Art for Nausicaä” via Pinterest

Suzuki proposed two projects: an adaptation of Richard Corbin’s Rowlf and a Sengoku period piece titled Nausicaä: Warring States Demon Castle. Unfortunately, neither was put into production. Rowlf would ultimately be shelved after the rights couldn’t be secured, and Warring States was rejected as Animage were unwilling to finance a project that wasn’t based on existing material. Stumped for ideas, Suzuki and Kameyama went back to the drawing board. Everything Miyazaki had was golden but none of it was based on an original work, leading to a series of rejections. So, they came up with a new plan. Why don’t we create our own manga, before eventually making it into an anime film? BINGO! Animage took the bait, and eventually, an agreement was met so that Miyazaki could provide his own artwork and story ideas under Tokuma’s strict condition that the project wouldn’t actually be made into a movie. Ironically, this project would be Nausicaä, a project which would not only spur Tokuma to redact this condition, but lead to the birth of Ghibli itself.

Nausicaä: Episode One courtesy of Animage

Nausicaä - The Film’s Manga Origins

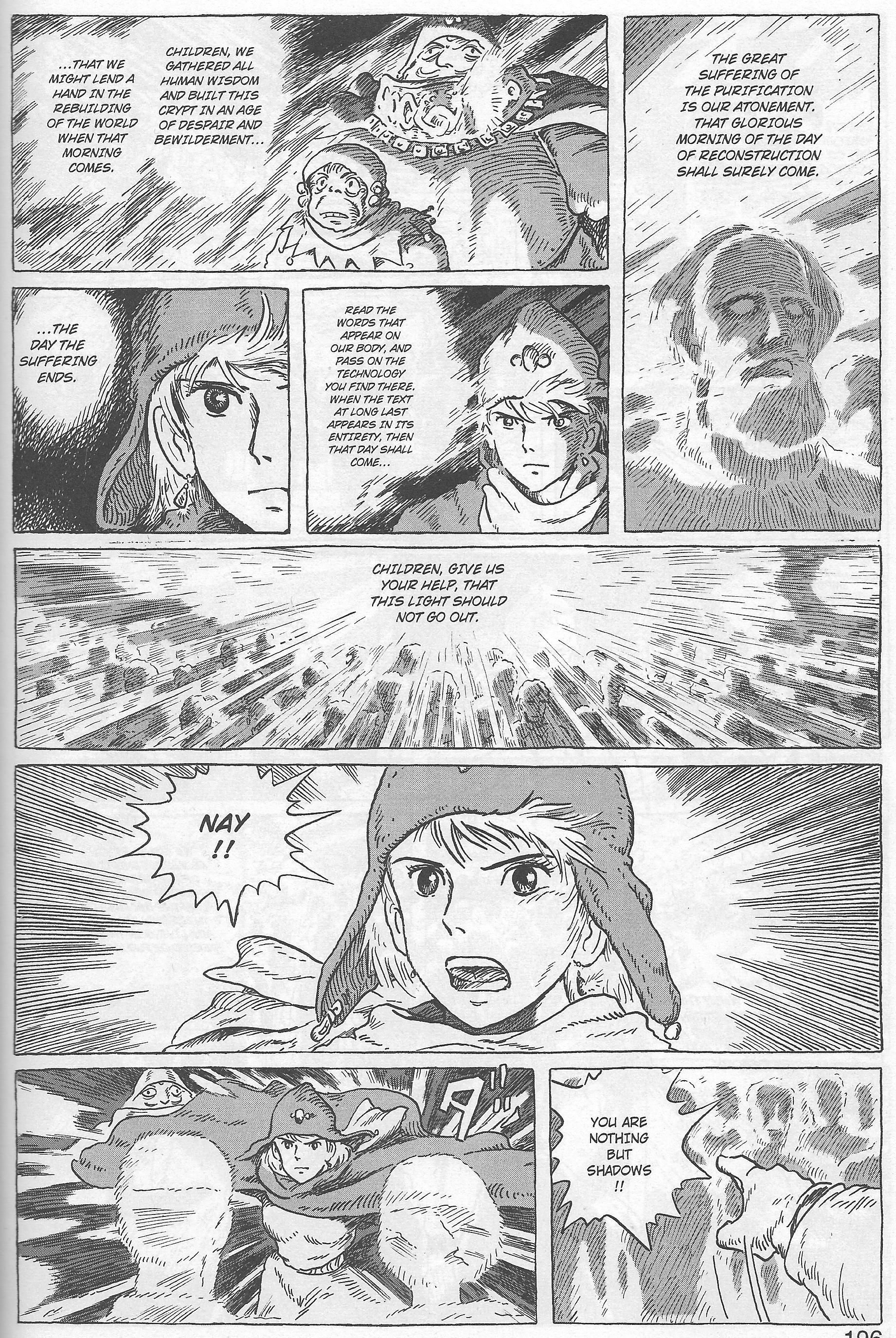

Utilising an innovative panel layout, one which was as thick as a brick, ensuring that readers would slow down the pace of their reading to fully absorb the material, Nausicaä’s style was polarising. With so many panels and lines of dialogue, readers and critics were struck by how dense it was.

Nausicaä courtesy of UK Viz Media

Other critics claimed it to be akin to the works of Moebius, a French comic book artist whose book, Arzach [1975] seemed an obvious influence on Miyazaki. Yet, despite their obvious similarities, Miyazaki refutes the claim, confessing, in an interview with the artist in 2004, that he hadn’t even read Arzach until 1980, and “By then, unfortunately, my style was fairly established. So I couldn’t use it as effectively as I’d have otherwise done in my creative development.”

From Left to Right: Arzach and Nausicaä

Distinct in terms of their approach from panel to panel, the worlds they depict are no doubt similar. Flying warriors inhabit the skies in Arzach, flying over desert-spanning regions inhabited by monsters and resting skeletons of giant animals. A change in colour palette and Nausicaä isn’t too different, as long as you read it in reverse.

From Left to Right: Miyazaki’s Arzach and Moebius’ Nausicaä via Miyazaki / Moebius - Exhibition Catalogue

The duo would remain friends until Moebius’ death in 2012, with each of them creating artwork honouring the other: Miyazaki a glowing image of Arzach in flight, and Moebius, an ethereal illustration of the Princess Nausicaä. Moebius was so enamoured by Miyazaki’s work, that he even named his daughter after the iconic anime heroine.

Nausicaä’s Transition Into an Anime

Back to Nausicaä now, which, despite Miyazaki’s reservations about his skill, soared in sales, quickly becoming Animage’s most popular feature. Seeing its franchise potential, Tokuma encouraged him to develop it into an anime film. While initially reluctant, with only two volumes of what was to be a seven-part series released by 1983, Miyazaki was eventually convinced of the idea under the strict condition that he would direct the film.

Assembling an All-Star Team: Miyazaki Recruits Anime’s Finest

Setting the precedence for all of Miyazaki’s later anime works – his penchant for strong female characters, themes of environmentalism and dedication to hand-drawn storyboards – Nausicaä, the film, would likewise form and/or strengthen the relationships he had with many of his future collaborators. Tokuma, Suzuki and, eventually, Takahata, would produce the film, each of whom would later aid Miyazaki in co-founding Ghibli, while many of the crew would form the backbone of the studio’s early films. Paradoxically, while never even meant to be made into a film, to discuss Nausicaä, is, in a sense, to discuss the birth of Ghibli itself. In 1983, due to the rampant success of the manga, the film started production, with Suzuki struggling to bring in Takahata to produce. It was an uphill battle as the Pom Poko director did not see himself as an effective producer for the project, believing that his history with Miyazaki meant that his involvement didn’t suit. He refused, with Suzuki recalling a moment when Takahata flat out rejected the proposal, handing him a note which read “that’s why producing doesn’t suit me” [2018].

Miyazaki Annoyed via @TheAVC

This didn’t sit well with Miyazaki, who felt betrayed by Takahata: “I devoted my youth to Takahata and he has never done anything for me” [Suzuki, 2018]. So, Suzuki spent two weeks attempting to sway Takahata to be involved with launching Nausicaä as an anime , even going so far as to beg him at his Tokyo doorstep, railing at him for betraying a friend in need. Eventually, Takahata caved, accepting the position under the pretence that an animation studio must be named before he would commit. In an interview for Kinema Junpo, Japan’s oldest film magazine, Takahata spoke about the process of getting Nausicaä off the ground:

“First, Tokuma Shoten [Tokuma Publishing Co.] had a magazine called Animage, and Miyazaki-san was writing the manga Nausicaa for it. Of course there were people who paid attention to it even back then, but it was a huge gamble to make an animation based on it. After all, compared to other manga writers, [Miyazaki] wasn't famous or anything. And Tokuma Shoten had no know-how, no studio, nothing. So what were we to do? We were confronted by a situation which was totally different from the one we grew up in. We had a project to do, and we had a head, [Miyazaki], but nothing else”.

They had a project, they had a director, but they didn’t have the crew. So, they went to TopCraft, an animation studio famous for its work on Rankin/Bass’ animated adaptations of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit [1977] and The Return of the King [1980]. Excited by the idea of working with Miyazaki, TopCraft joined the production, and Nausicaä finally went underway, marked for a 1984 release.

A Poster Nausicaä

Michiyo Yasuda- The Colorist of Dreams

Outsourcing most of the animation to the team at TopCraft, Nausicaä’s production also employed a slew of Miyazaki’s early connections at Toei Studios. Takahata specifically ensured to bring in soon-to-be legendary Ghibli colourist, and fellow Toei comrade, Michiyo Yasuda.

Michiyo Yasuda via @chasekendall1

Responsible for Nausicaä’s vast array of colours, Yasuda had already proven herself as an exceptional tracer on Horus, way back in the day, moving steadily along the animation ladder, until eventually assigned the colour selection for the entirety of Future Boy Conan. “I love her craftmanship,” Takahata stated, “Not only is she capable of her job, but she can also see the whole picture.” Thus, when a colourist was in need to take on the daunting task of Nausicaä, Takahata need look no further: “I want [Yasuda] to be in the centre of the team when I make a film.”

The Toxic Jungle Courtesy of Studio Ghibli

Colouring Nausicaä would be no simple task. This was before the digital era, and thus everything had to be hand drawn, with any practical effects, made from scratch. The trilobite creatures, the Ohmu [Ohm in the manga], were designed using multiple layers of paper, moving each section to give the illusion of movement, while saving on animation costs. Miyazaki wanted Nausicaä’s animation to be simplistic, yet vibrant, with each of the insects inhabiting the Toxic Jungle to be the same shade of blue to blend in. This idea was ultimately dropped to better distinguish the various insects.

Nausicaä Colour Pallete courtesy of Movies in Colour

Sporting a monumental 263 colours, far eclipsing the standard volume of colours used for anime at the time, Yasuda was a seminal find for Nausicaä and the future of Ghibli, taking on the role of colourist on each of Miyazaki’s subsequent films; even coming out of retirement in 2013 to work on The Wind Rises. Proving that colour was an essential beat in the rhythm of Miyazaki’s heart, Yasuda was described by critic, Brian Camp, as a “mainstay of [Ghibli’s] extraordinary design and production team” [2007]. Sadly, Yasuda passed away in 2016, leaving behind a lifetime of achievement at Ghibli.

Hideaki Anno:Animation’s Skilled Newcomer

Filled with genius animators, such as Takashi Nakamura, Nausicaä’s animation department was fortunate to be hired by the likes of Takahata and Miyazaki. Being animators themselves, they knew the incredible efforts needed to produce even the most simple animation. Thus, they paid their animators per frame, ensuring that they would receive a fair and substantial wage for their work.

One of the animators to benefit from this wage was a certain University dropout who arrived on the scene after Suzuki left a call for help in Animage magazine. Due to Miyazaki’s demanding standards, the anime was running behind schedule. Storyboards were coming up slowly and animation sheets even slower. So, in 1983, Animage printed an urgent call for more animators to help with the feature. “Then, one day he just showed up,” Suzuki recalls in the documentary, The Birth of Studio Ghibli, “afterwards I realised how much guts it must’ve taken to walk right in and hand Miyazaki samples of his work” [1998]. Those guts, Suzuki mentions, belonged to one, Hideaki Anno.

Anno circa 1980 via @Josh_Dunham

The later creator of one of the most revered anime of all time, Neon Genesis: Evangelion [1995], Anno bust open Miyazaki’s doors and handed him his portfolio. A brash decision that paid off as Miyazaki immediately hired him to work on one of Nausicaä’s key sequences, the God Warrior scene.

Depicting a giant humanoid weapon of mass destruction, Miyazaki was adamant that this scene be something audiences had never seen before. “Miyazaki wanted something with impact, very detailed, with a unique sense of movement,” said Suzuki in 1998, “It’s really a high point of the film.” Spending the next three months working solely on the 90-second scene, Anno knocked it out of the park, producing a visceral moment of jaw-melting animation.

According to Suzuki, Miyazaki was incredibly satisfied with Anno’s work and the two have remained friends ever since. “[Anno even] considers Evangelion a continuation of Nausicaä, done in his own way,” Suzuki wrote in a discussion with Bungei Shunjū, “It’s amazing how much he was influenced by Nausicaä. Those short three months he spent at our office ended up defining everything about him.” Anno would collaborate again with Miyazaki on The Wind Rises, where, instead of animating a giant, civilisation-destroying kaiju, he provided the voice for the central, pacifist character, Jiro Horikoshi.

Joe Hisaishi- The Iconic Voice Actor

Another collaborator who would return to work with Miyazaki time and time again was the one and only Joe Hisaishi, experimental music producer, and soon-to-be iconic film composer. Recommended by Tokuma, who had published Hisaishi’s first album, Introduction in 1982, Takahata hired Hisaishi to produce an image album for Nausicaä. Utilising a mix of synth and orchestral instruments to connote the futuristic world of the Periphery, Hisaishi created a score embittered with discordance and strife, juxtaposing “elements from Late Romantic orchestral styles, 80's synthesizer loops, “electro-rock” and synthesized “Indian” music” [Cue by Cue, 2016].

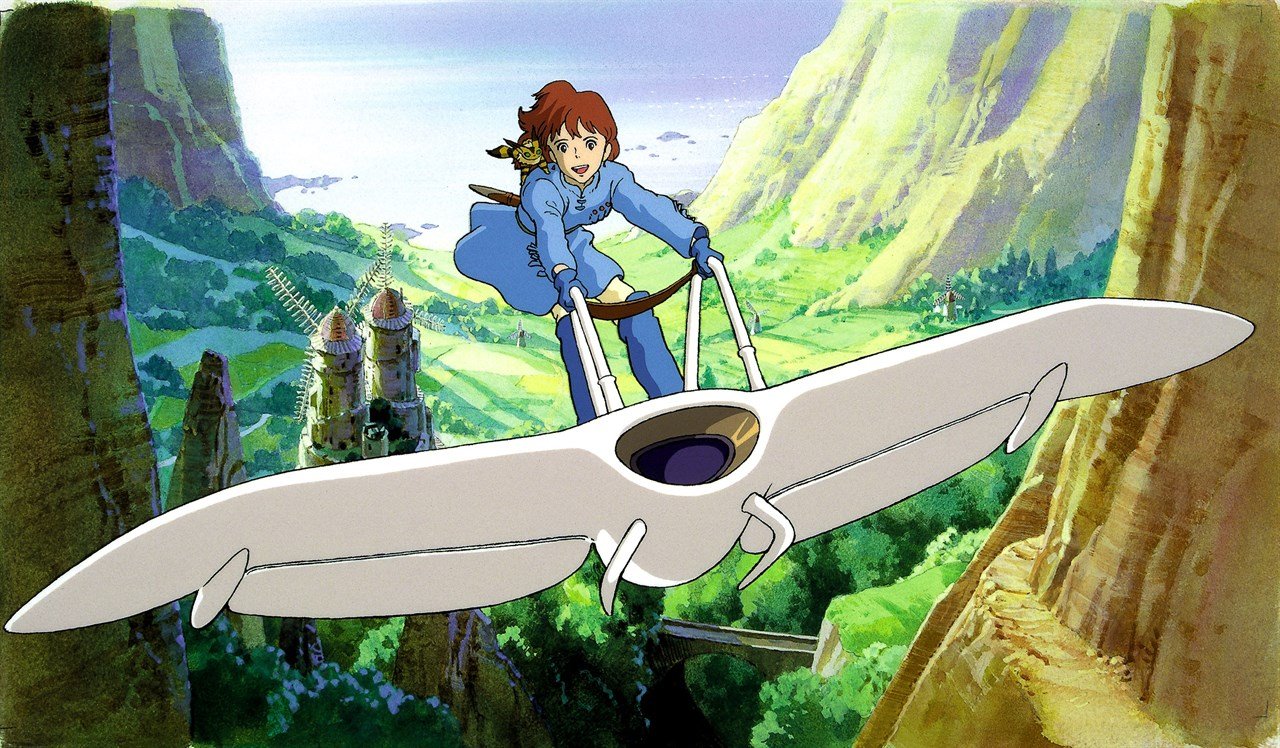

According to Hisaishi, he was inspired by Miyazaki’s depiction of flight, stating that “many of [Miyazaki’s] works have flying scenes and flying has always been the dream of human beings. So I tried to connect this feeling of hope to the spirit of these scenes. Music that is slower. That allows the audience to experience what’s in the space between movements” [cited by STEVEM, 2021]. Hisaishi would of course return to work with Miyazaki for each of his later films, celebrated for turning the director’s human touch into music.

Nausicaä’s Legacy-The Formation of Studio Ghibli

Never intended to be made into a film, Nausicaä would inadvertently sow the seeds of Studio Ghibli. Bringing together many of Miyazaki’s future collaborators and enjoying a successful release which would catalyse the studio’s creation. Shortly after the film’s release, TopCraft went bankrupt, and Tokuma advised Miyazaki to use the success of Nausicaä to create his own studio, capitalising on the team he’d already built to jumpstart a new venture. Takahata recalls a moment when he urged Tokuma to support them in the formation of Ghibli, asserting “that if Tokuma Shoten was seriously going to produce animation in Japan, we had to do it responsibly, with a long term view, not just doing it when we had a project, renting some studio and then disbanding it [after the project has completed]. So, it was decided to form Ghibli.”

Nausicaä Flies Over the Valley of the Wind Courtesy of Studio Ghibli

With Tokuma coming on as co-founder, along with Takahata, Suzuki and Miyazaki, in 1985, Studio Ghibli was born, taking a chunk of Topcraft’s jobless staff and forming a dream team of dedicated animators. Miyazaki even named the studio after his favourite Italian aircraft, the Caproni Ca.309, nicknamed “Ghibli,” which in Arabic means “desert wind.”

After Nausicaä, a Lasting Impact and a Sequel?

Nausicaä remains Miyazaki’s most formative work, providing the basis for his sophomore feature, and, in turn, laying the foundations of Studio Ghibli. Sporting various video game adaptations, an infamous American cut, and even a short film prequel co-produced by Ghibli and written by Hideaki Anno, the world of Nausicaä is immersive, boundless; filled with provocative imagery and prescient foresight. It’s so big that it’s one of the few Miyazaki works that could benefit from a sequel; or another means to explore the expansive dystopia. And it’s one of the few times Miyazaki agrees, but only if Anno is the one to helm it.

Giant God Warrior Appears in Tokyo in Anno’s Nausicaä Prequel Short Film via Opus

During a television interview, Miyazaki was asked if he was interested in making a continuation or part 2 of Nausicaä. He replied, “No, I don't. I don't really feel like doing it, but Anno keeps on saying, 'I want to do it! I want to do it!,' so I tell him now that I've come to think lately that if he wanted to do it, it would be fine for him to do it” .

Miyazaki and Anno. Who Needs University When You Have Miyazaki on Your Side? via @ghibliotheque

And there you have it, folks. If there was ever to be a sequel to Nausicaä it would come from the man who designed the God Warrior himself. The only caveat, he wants to do it in live-action. A big no-no for director Miyazaki. Sad luck, Anno. Though, who knows, maybe Miyazaki will come around... but don’t hold your breath. The guy is not a fan of live-action 3D animation.

About the Author

Writer, screenwriter and lover of all things Japan, Simon Jenner explores stories through art and culture. Connect with him for articles about film, anime, gaming and more.