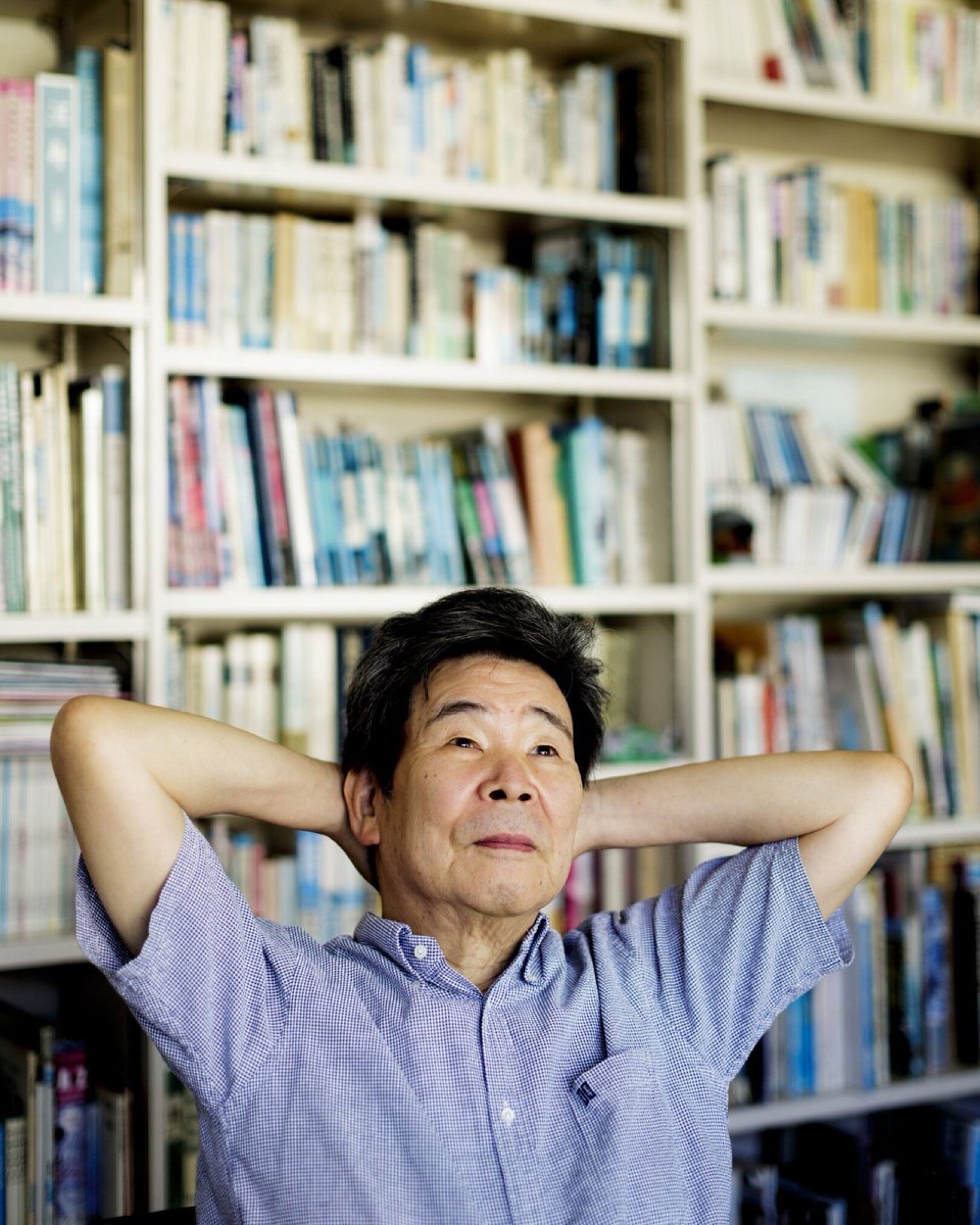

The Overlooked Masterpieces of Isao Takahata

The words “Studio Ghibli” and “Hayao Miyazaki” are near-synonymous with each other. The former being the acclaimed Japanese animation studio and the latter being the co-founder and director of many of its famed works.

However, when discussing the monumental achievements of Miyazaki, who conceptualised such masterpieces as Spirited Away [2001], Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind [1984] and My Neighbour Totoro [1988], the propensity to neglect the other filmmakers of Ghibli is unjustly apparent.

One of these filmmakers, in particular, was the late Isao Takahata, whose works at Ghibli have all but succeeded in eclipsing the artistic accomplishments of Miyazaki while failing to attain the same level of reverence and prominence. With such notable inclusions as the pensive Only Yesterday, the folkloric Pom Poko, the familial My Neighbours the Yamadas, the exquisite The Tale of the Princess Kaguya and indeed the renowned Grave of the Fireflies, Takahata’s portfolio is as eclectic as it is transcendent; proving in dramatically varied styles the mastery of the esoteric filmmaker. And yet, the scope of awareness which these films achieve is far outshone by the works of Miyazaki, largely in part due to their considerably more adult themes and Takahata’s penchant for more complex and diverse storytelling.

Takahata’s noted pieces are visually distinct from one another. While Only Yesterday, Pom Poko and Grave of the Fireflies are more in-line with the typical hand-drawn animation style of Ghibli, his latter films - The Yamadas and Kaguya - are considerably more experimental in approach. The Yamadas is presented in a stylized comic strip aesthetic, while Kaguya is drawn in minimalist style, utilising redolent watercolours and charcoal strokes that seem to evoke traditional Japanese ink paintings, or even Takahata and Miyazaki’s earlier work on the animated TV series Heidi, A Girl of the Alps [1974]. It could be argued that it was Takahata’s inability to refrain from his relentless experimentation that resulted in the lesser degree of recognition of his otherwise critically acclaimed body of work.

Considering this lack of awareness of Takahata's eclectic portfolio, we’ve decided to shine a light on the somewhat underappreciated filmmaker, his polished works at Ghibli, and to give credit to one of the most important creators to come out of Japan. Exploring the lesser-known works of one of Ghibli’s co-founders, while illuminating pieces which have otherwise been side-lined by the myriad achievements of the prestigious animation house; this is Sabukaru’s mini-guide to the often-overlooked masterpieces of one Isao Takahata.

Grave of the Fireflies

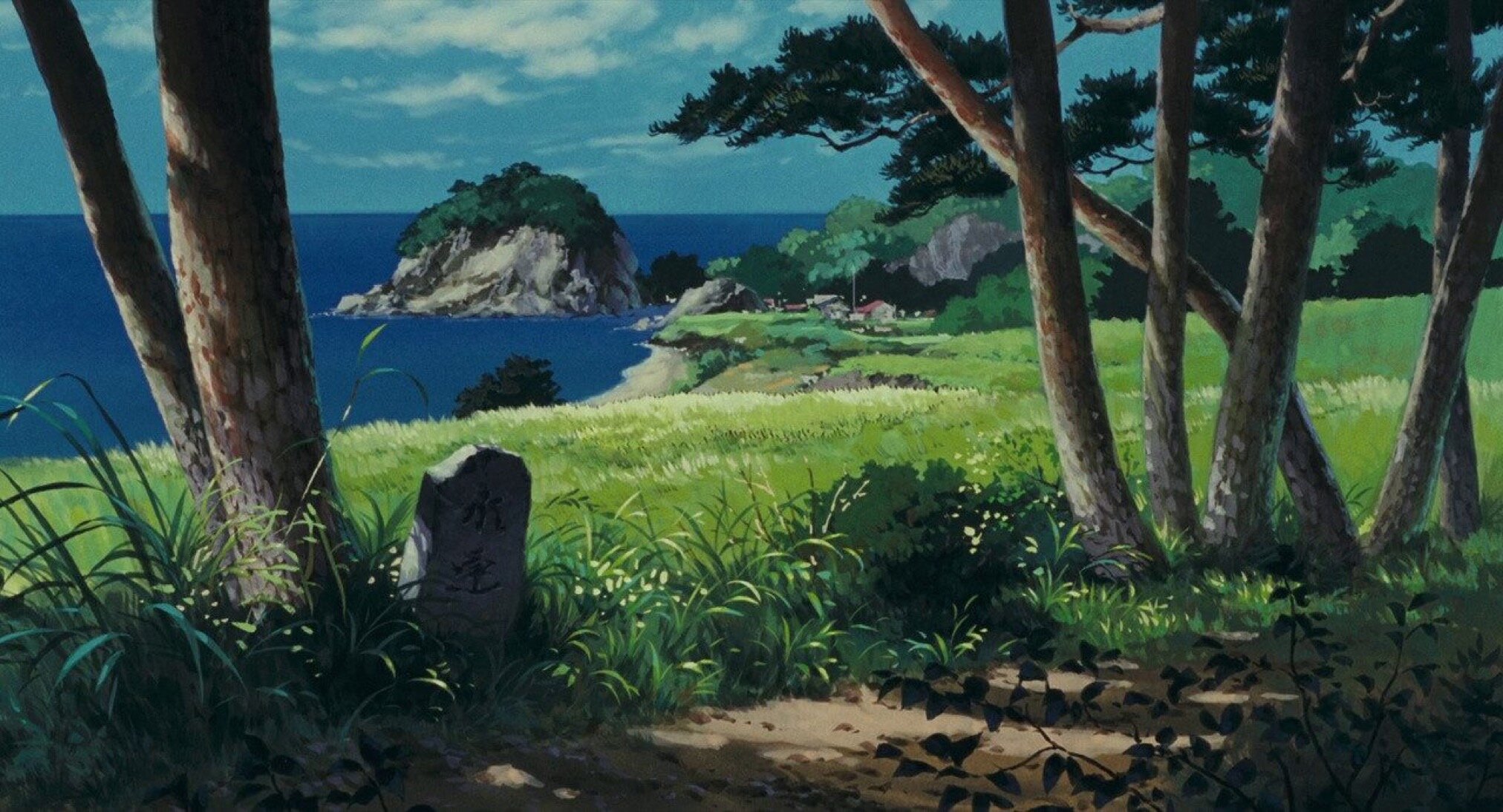

The first and arguably most significant piece in Takahata’s exemplary filmic array is the 1988 wartime parable, Grave of the Fireflies.

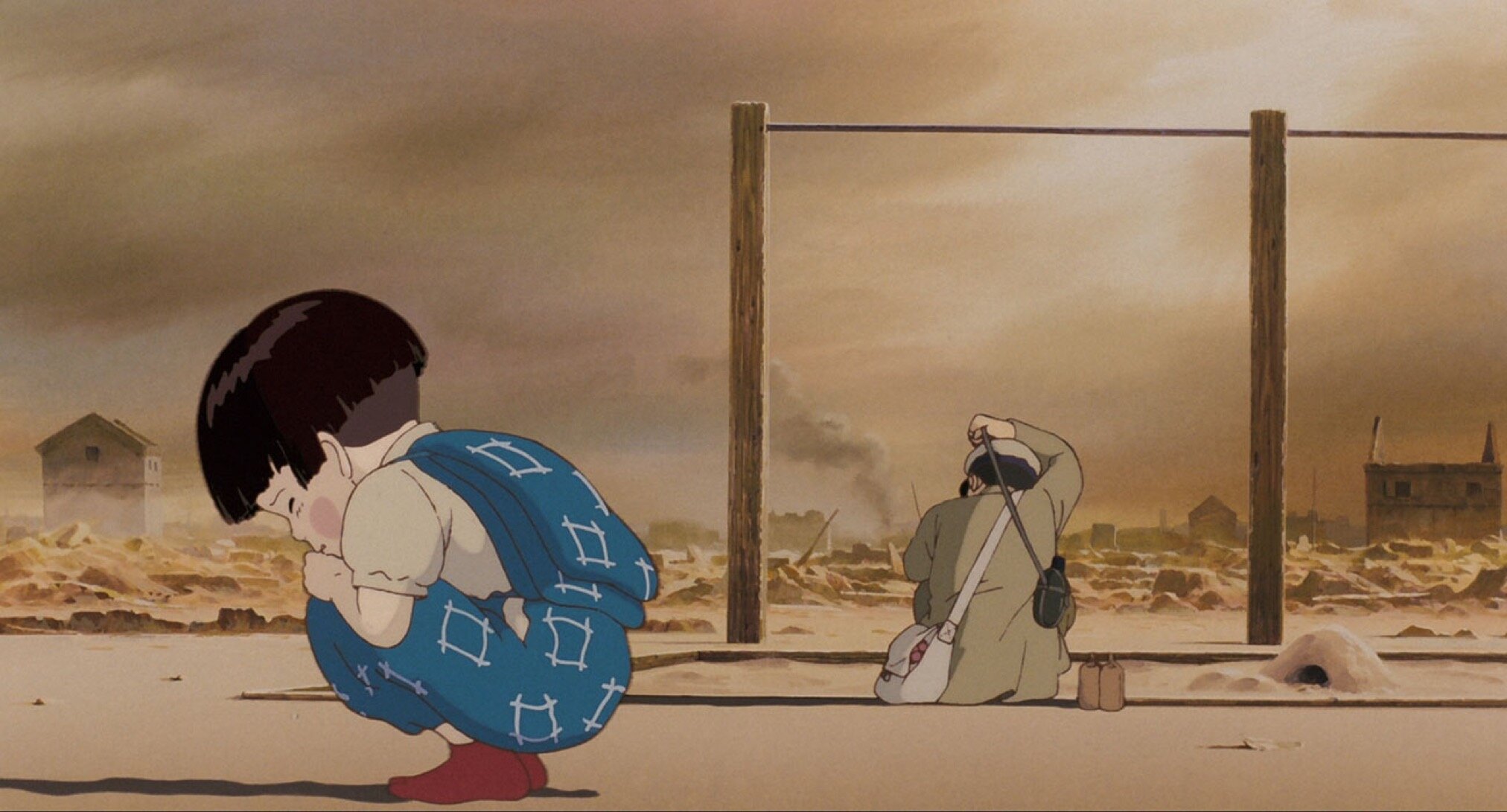

Depicting a tale of the utmost woe, Takahata’s seminal anime film is set amidst the backdrop of World War Two and explores the impact that the global conflict had on the citizens of Kobe, Japan. Following Seita, a teenage boy whose lifeless body is found in the confines of Kobe station, the film backtracks months earlier to recount the tragic events that led to his eventual death.

After their family house and most of the city is destroyed in a firebombing, Seita and his infant sister, Setsuko are forced to live on the streets; scouring for food and searching endlessly for a semblance of hope in an otherwise dire existence. Turning to a nearby bomb shelter for survival, the two manage to find solace in their own company, capturing and releasing fireflies at night for light, and rationing a tin of Sakuma drops [a hard candy from Japan] to keep up their health.

Yet, as their rations shrink, Setsuko begins to elicit hallucinations; eating dirt and sucking on marbles in place of the candy, while her brother struggles to find supplies in the city. Things go from worse to worst as Seita discovers that his sister is suffering from malnutrition, and as the end of the war portends it becomes increasingly evident that their father might never return from the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Based on the 1967 semi-autobiographical short story of the same name by Akiyuki Nosaka and released in the same bill as Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro, as a more adult counterpart to the seminal children’s animation, Grave of the Fireflies initially turned audiences away due to its dire portrayal of wartime Japan and the pernicious repercussions of the military’s refusal to surrender to the allied forces. Yet, over time the film has received near unanimous praise for its bold storytelling and poignant depiction of the grim consequences of war on a society, and the individuals therein. What’s odd is that Takahata himself insists that the film is “not at all an anti-war anime and contains absolutely no such message” but instead, offers a portrait of a brother and sister brought to desperation by isolation and societal neglect. This suggests that the film, which utilizes so explicitly the horrors of war, is but an avenue to discuss a larger human inconsistency; namely, our ability to ignore and remain apathetic to the prospect of extreme poverty, suffering and inequality; even when it’s staring us in the face. Seita and Setsuko are bereft of support, rejected by society and forced to reside on the fringes of Kobe city. Even the sibling’s aunt, who is shown to live in relative comfort in the heart of the city, pushes the children to sell their mother’s clothing; their sole reminders that they were once loved and cared for. Now neglected and dehumanised, the aunt later becomes resentful of the children, which thus informs their decision to move into the bomb shelter, resulting in their fatal circumstances and informing the overall hopelessness of the film. Society, in Grave of the Fireflies, is amoral and utterly spent.

Takahata later clarified his statement in an interview with Japan Times, proclaiming that “Japan was devastated by the war [...] We should never forget that, just as we should never forget that we also inflicted a lot of suffering on other countries. However, nobody knows how horrifying a war is going to be at the beginning of hostilities. Grave of the Fireflies isn’t an anti-war film simply because it cannot prevent another war from happening”.

Takahata’s statement, along with the parabolic nature of the film, implies that, while Grave of the Fireflies may not, in his opinion, be an anti-war film; it is inherently an anti-suffering film. Clarified by this notion that war is inevitable, Takahata manages to instil a sense of progressive thinking to his otherwise woebegone piece; that while conflict is an innately human process, and one that will continue to shape the future of our species, reflection and empathy are intrinsically human too. While we may fight and argue, kill and be killed, our ability to identify with the suffering brought on by war and societal neglect makes us inherently reflective and capable of change.

Whether hopeless or hopeful, an anti-war film or a piece of cinema that directly responds to the oftentimes impassive nature of humankind, Grave of the Fireflies remains an integral addition to the incredible works of Ghibli and the first in Takahata’s diverse array of anime films for the pioneering animation house.

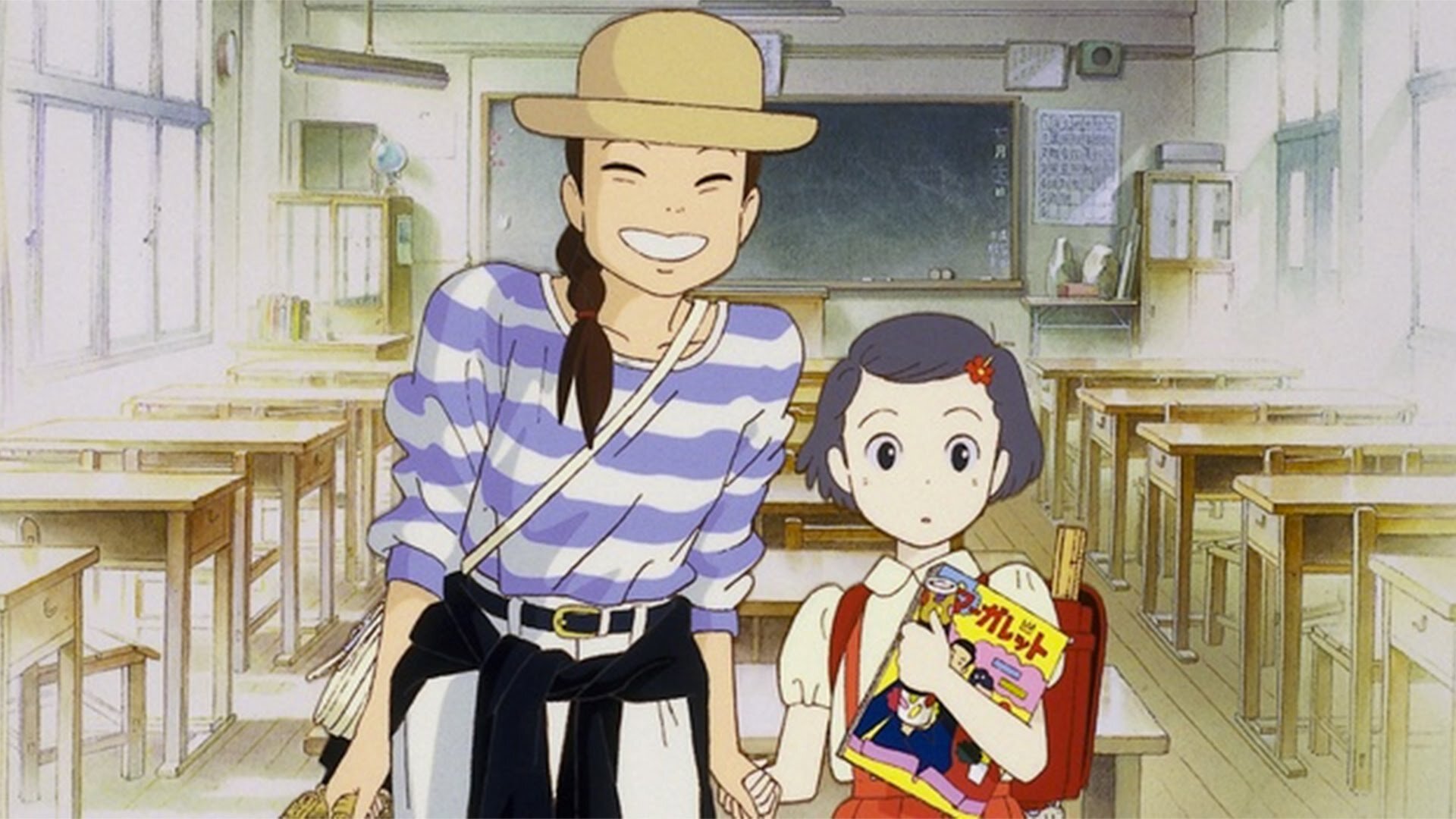

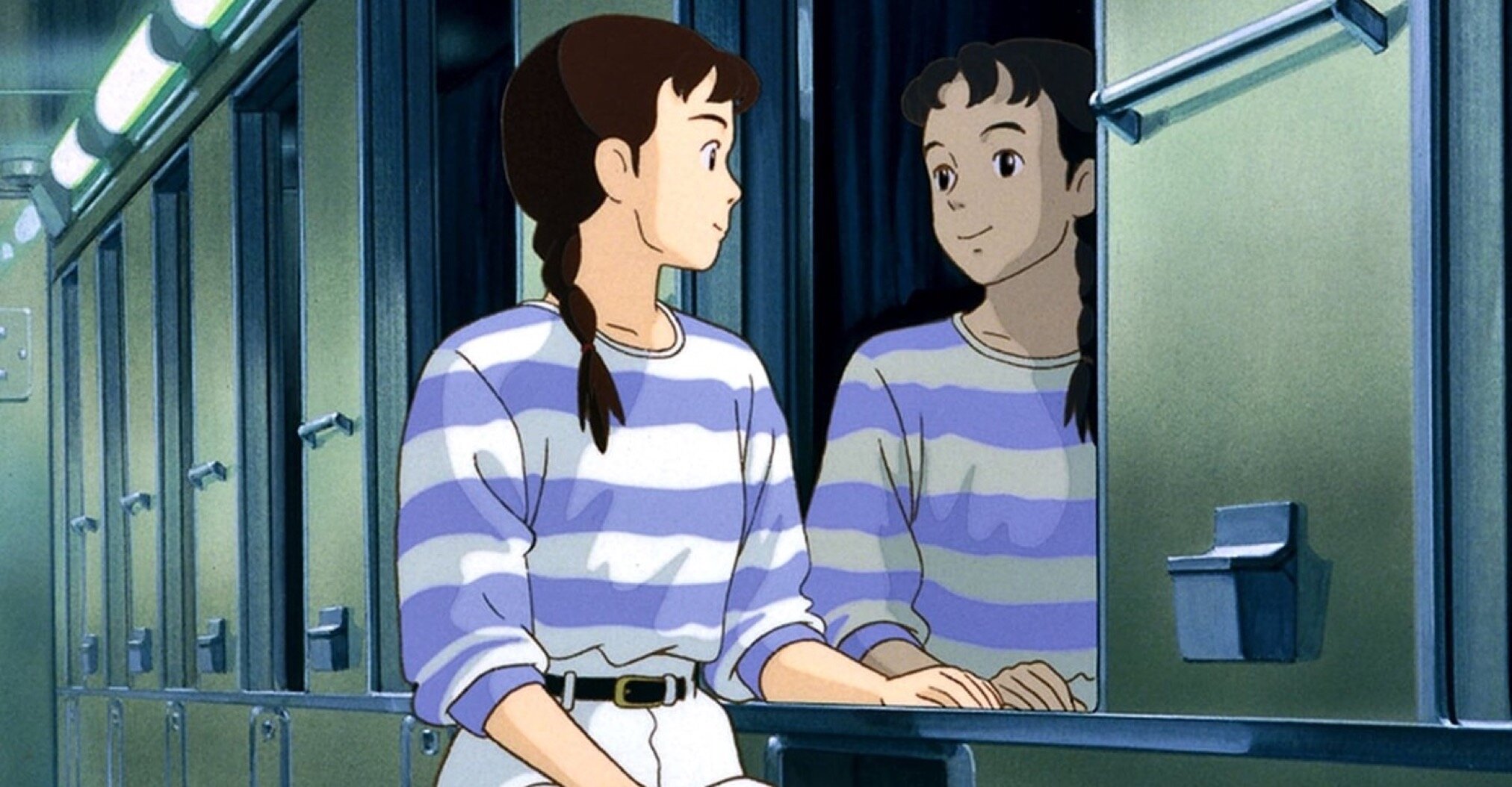

Only Yesterday

Takahata’s next film, while maintaining a fascination for those living against the grain - away from the metropolitan and amidst the rural - is utterly separate in its themes, characters and subject matter. Released in Japan in 1991, and based on the 1982 manga of the same name by Hotaru Okamoto and Yuko Tone, Only Yesterday follows the tale of Taeko Okajima, a 27-year-old kyariaūman [career woman] with an appetite for the rural. After living her entire life in Tokyo, Taeko decides to take a trip to the countryside so as to visit the family of the elder brother of her brother-in-law, and to assist with the annual safflower harvest.

Upon arriving, Taeko begins reminiscing about her past, her childhood dreams of escaping the big city, her jealousy of those with family in the countryside and her want for a more tranquil and hands-on existence. She begins having flashbacks of her childhood - her first taste of pineapple, her first crush, her first period - all the while establishing a newfound affiliation for Toshio, her brother in law's second cousin and the catalyst for much of Taeko’s contemplation. Battling with adult notions of career and love, Taeko starts to question her life choices, exposing a burgeoning desire to stay true to her childhood dreams and escape to the countryside.

Creating a pseudo iris effect, each flashback is bordered by a washed-out whiteness that imbues the film with an appropriate obscurity. Taeko’s memories are incomplete, fractured; triggered by either extreme happiness or painful experiences. The film exposes the inherent notion that memory breeds incoherence, and with that, the ability to reminisce or recoil at the slightest joys or lowest woes. Yet, while these memories may detract from fact, they convey resonant emotions that work in tandem with the overall contemplative nature of the piece. While Grave of the Fireflies explores the terrors of human nature through abject suffering and mournful neglect, Only Yesterday conveys the lulling essence of nostalgia and our ability to reflect on past mistakes. As the former recounts the extremes of human apathy, fallibility and the terrible misdemeanours of a society thwarted by war, the latter - albeit from a much more personal point of view - explores the transient nature of memory and the capability of human change.

Culminating in a charming and chiefly poignant picture, which will leave many yearning for the wistful tranquilities of childhood wonder and the reflective qualities of memory and nostalgia, Takahata’s seminal coming-of-age drama is strewn with poignant notions of reminiscence and regret, yet free from repugnant or terrible circumstances. The film is purposely lighthearted, yet, through its resonant subject matter, is able to penetrate deeper and more profoundly than perhaps his more celebrated pieces. Wistful contemplation captured oh so eloquently, Only Yesterday explores the intrinsic nature of humankind to reflect on the good, the bad, and the ugly moments in our past, without being damning or overly serious.

Rejected by Disney for international distribution due to the film's propensity to explore the adult notion of menstruation, Takahata’s Only Yesterday is an understated study of the transience of memory, the power of retrospection and humanity’s ability to adapt to life and life’s encumbered echo.

Released in the west as of February 26, 2016 [thanks to American film distributor, GKIDS], Only Yesterday is now widely available to watch and re-watch at your leisure.

Pom Poko

Deviating from the predominantly human sensibilities of his initial works at Ghibli, Takahata would then go on to further expose his appetite for experimentation by way of his next feature; the allegorical and mischievous, Pom Poko [1994].

Depicting a nursery of magical tanuki [Japanese raccoon dogs], who struggle to resist the threat of suburban development from destroying their home forest on the outskirts of Tokyo, Pom Poko is by and by a prophetic vision of humanity’s continued destruction of the environment and the animal habitats therein. Told through overt symbolism and on-the-nose metaphor, the film presents prescient notions of environmentalism, community and, much like Grave of the Fireflies, the consequences of apathy and neglect with regard to humanity’s callous nature... for nature.

Opening in late 1960s Japan, the film spans over 30 years, resuming later in the early 90s where despite the tanuki’s best efforts, the gigantic development project known as New Tama, is still set to go ahead. Led by the aggressive chief Gonta, the old guru Seizaemon, the wise-woman Oroku, and the young and resourceful Shoukichi, the tanuki must utilize their near-forgotten powers of illusion to stage eco-terrorist attacks on the oncoming construction; shapeshifting, floating and extending their scrotums to massive sizes in order to fight, bounce and parachute their way to conservationist war.

Yet, while causing havoc in abundance - including the inadvertent deaths of a few humans - the tanuki's efforts are ultimately in vain, as no matter how hard they fight, humanity’s penchant for expansion and industrialisation is irrepressible. However, with a few tricks still up their anthropomorphic sleeves, the tanuki’s fight is seemingly never over; instead, merely evolving with their newly refreshed magical powers and their budding adaptation to human civilization.

Repeating, with Pom Poko, his nascent woes about society and our ambivalence to the harm caused by humanity’s destructive nature, Takahata interweaves these parabolic notions throughout this chiefly fantastical piece. As with the siblings in Grave of the Fireflies, the tanuki are subject to neglect and suffering at the hands of humanity. Their home is threatened by industrial institutions, their way of life altered drastically by the destructive innovations of humanity, and indeed, as per Takahata’s earlier thoughts on his prior wartime anime film, he provides no answer to how we must combat it; recalling his apathetic belief that conflict is inevitable, albeit this time focussing primarily on the expansion of man.

It is arguably rather hopeless the extent to which the tanuki must adapt to survive the oncoming industrial onslaught; shapeshifting finally into a grand picture of the beautiful landscape of which the humans so carelessly want to destroy. An epithet of environmentalism that, while moving for a moment, ultimately only slows the suburban development; forcing the tanuki to find new ways to adapt to human civilization. They begin blending in with their oppressors, rummaging through trash and essentially becoming the verminous animal many see them as today. It is sadly telling that the resolution of Pom Poko is one of adjustment rather than victory, reiterating Takahata’s woeful feelings towards human development and the callousness of our actions upon the world and each other.

Deriving its name from the sound made from the tanuki pounding their bellies - a form of Tanuki-bayashi, otherwise known as baka-bayashi [a strange supernatural phenomenon talked about in legends across Japan] - Pom Poko is a wonderfully symbolic and thought-provoking piece of environmentalist cinema. Taking notes from Miyazaki’s more well-known environmental works such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and translating those fateful epithets into an exceedingly local story of legend and laughter. As, while the film is strewn with prophetic notions of human apathy and environmental destruction, it is also a largely amusing piece of art; boasting the, aforementioned, slightly odd depiction of the tanuki using their testicles in their struggle against oppression.

My Neighbours the Yamadas

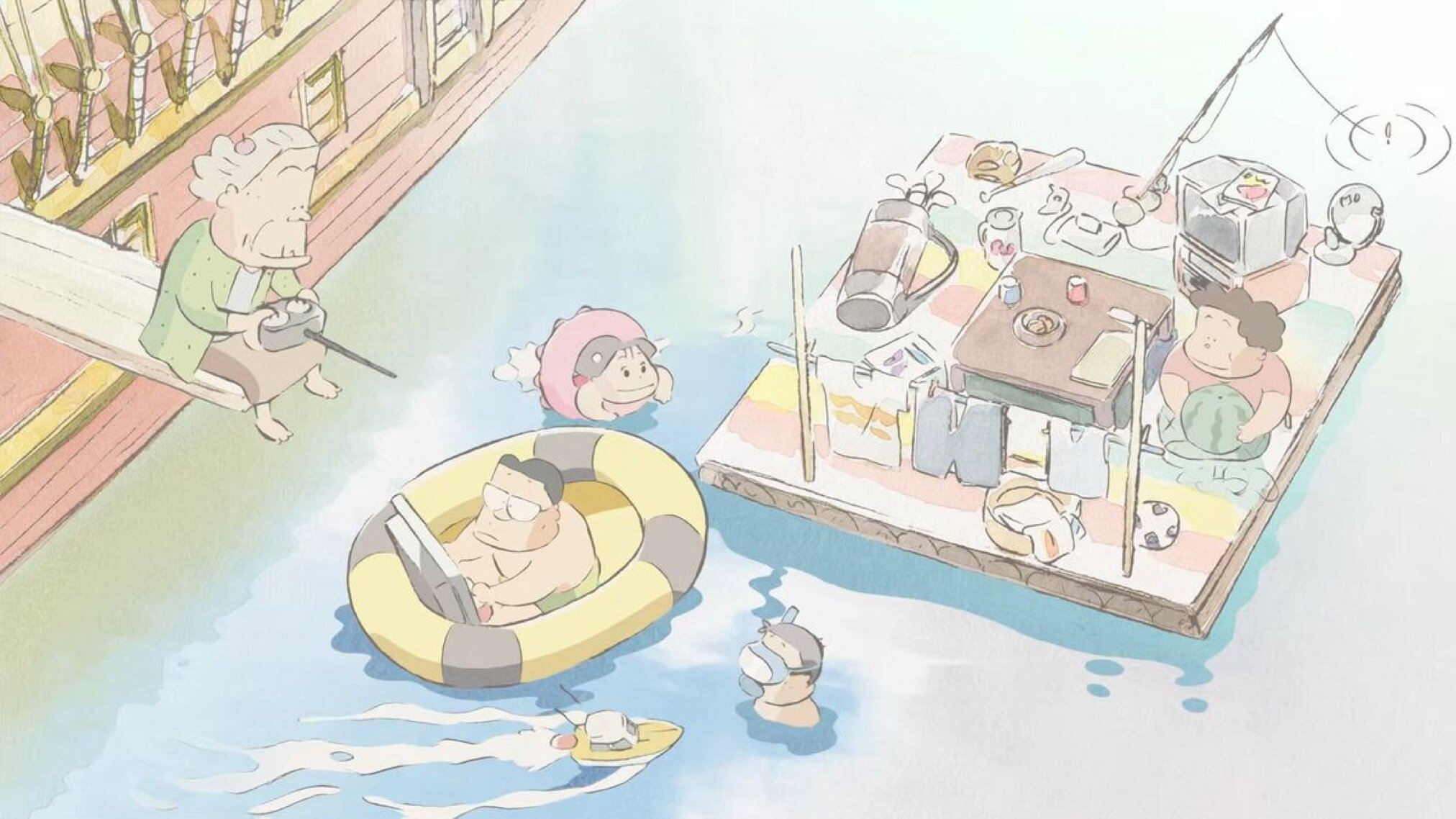

While Pom Poko saw Takahata’s initial venture into experimentation with regard to storytelling and character, it was his next directorial effort that truly cemented his passion for innovation. The first completely digital Ghibli film, My Neighbours the Yamadas [1999] is a stylistically unique, comedy drama that explores the daily lives of the Yamadas family as they laugh and bicker in this penultimate directorial effort from Takahata for the venerable animation house.

Exceedingly small-scale in terms of its subject matter and overall narrative, My Neighbours the Yamadas is a light-hearted, unapologetically personal tale of familial love. Transposing cultural boundaries to explore a tale of universal resonance, Takahata’s seminal slice-of-life film is told throughout various vignettes that depict the lives of the Yamadas and the relationships they maintain therein. Whether it be the connection between father and son, the wisdom of age, or simply the reminiscent account of leaving one’s child at a department store, The Yamadas is consistently trivial in its narrative concern, yet wholly relatable in its depiction of family.

While arguably absent in terms of plot, the film is wonderfully intricate in its study of character. Each and every member of the Yamadas family is strewn with individuality and endearing personality. The father, Takashi is an overworked salaryman, whose daily existence generally consists of smoking cigarettes, moaning at life’s shortcomings - such as a loud group of bikers plaguing their neighbourhood - and occasionally playing the goofball, as many fathers tend to do. The mother, Matsuko, fits securely into the traditional role of the housewife; cooking, cleaning and generally ensuring the day-to-day activities of her family, while lamenting at their continued negligence of her exhaustive efforts. Noboru, the elder child and only son of the Yamadas, is the unexpected straight man of the otherwise comedic collection of characters, whose unabashed seriousness permits additional laughs when contrasted with his elder’s tomfoolery. Then there’s Shige, Matsuko’s elderly mother, who personifies, in hilarious fashion, the aforementioned wisdom of age and the haughty know-it-all nature that comes with being the family matriarch. Finally, there’s Nonoko, who, as the youngest member of the Yamadas, acts principally as a sprinkling of cuteness on the chiefly squabbling antics of the film’s characters and the punchline to many of its jokes.

While each and every character is unique, they do tend to suit the general stereotypes that they are indebted to. The father as the office worker, the mother as the housewife, the son as the teenager who finds embarrassment in everything his family does, the stubborn grandmother and the innocent toddler. It could be argued that this is a potentially problematic view of a proposed “normal” family, whose gender, behaviours and familial roles subject them to the constraints of societal normalcy. Yet, as per its zany comedy and relatable deconstruction of familial life, as well as its success in showing a family outside of the general western interpretation - albeit one from a generic nuclear standpoint - the film is mostly harmless and wonderfully endearing. It is one of those movies which, although debatably destitute of plot, is brimming with notions of life, relationships and love; exploring these facets extensively yet without over-encumbering its Lilliputian narrative. It is a succinct portrait of the familial, a slice of family life based on the yonkoma manga Nono-chan by Hisaichi Ishii, and presented on-screen by one of Japan’s leading anime filmmakers.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

After proving, in spades, his inclination for innovation within the sphere of animation, Takahata would proceed to take a prolonged break from the director’s chair; providing his talent only for a short segment in Kihachirō Kawamoto’s Winter Days [2003] and in curating the first six episodes of his popular 1970s anime series, Anne of Green Gables, into a feature length movie in 2010. With seemingly no other cinematic endeavour in mind, it became apparent that the master filmmaker, who was emerging into his mid 70s, might be done with the world of anime film. That is, until long-time fan and chairman of Nippon TV heard rumour that Takahata wanted to direct one more film before his eventual retirement; a film that was set to be based on The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, a 10th century monogatari considered to be the oldest extant Japanese prose narrative in history. Consequently, after Ghibli announced the film’s production in 2008, the aforementioned chairman, Seiichiro Ujiie, would prove his desire to see Takahata’s final film put to screen by providing ¥5 billion [approximately $40 million] to the production before his untimely death in 2011. And while Ujiie was unable to achieve his wish of seeing one more Takahata film, he was at least able to read the script and view some of its storyboards prior to his death.

Ever since reading the original text in his childhood, Takahata had been obsessed with recreating the legendary Japanese folktale for the silver screen; finding difficulty however empathising with its protagonist and subsequently wanting to extend the story in order to fully realise the eponymous Kaguya. He would utilise this return to childhood wonder to help conceptualise the film, as stated by Michael Toscano of Curator Magazine, that while Miyasaki, post The Yamadas, ventured further into the digital realm of animation, “Takahata returned to the spirited days of a youthful sketch artist”, implementing his “great skill [with] design [... in] rejection of the technological smoothness and denseness of the computer generated image”. And thankfully so as, despite its long production and limited western release in 2014, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is by far the most visually splendid in Takahata’s repertoire of anime masterpieces; and, returning to Toscano, “one of the most arresting animated films ever made”.

After years of production, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya was finally released in Japan in 2013, and was met with near-unanimous praise for its bold art style and propensity for narrative stillness. Takahata’s final film illustrates in painstaking detail the fantastical tale of a mysterious girl, named Kaguya, who, as a baby, is found nestled in the stem of a bamboo plant.

Lauded for its refined use of metaphor, the film proceeds to present the tale of Kaguya as she enjoys, consumes and struggles with life’s gifts as well as its shortcomings in this magical tapestry of anime wonder. She is shown enjoying life in the countryside with her father and mother, enthralling all who witness her elegance and her brimming supernatural powers. Kaguya grows rapidly, becoming a full-bodied woman in a matter of weeks and stunning those around her with her beauty and charm. All is well until her father begins to employ certain institutions to govern Kaguya’s freedom and future. Searching for suitors near and far, her father works tirelessly to find a partner who could match his daughter’s divinity. Through this, Takahata exposes, with poetic resonance, the constraints placed on women by patriarchal systems of governance, matrimony and objectification. Kaguya, once a blossoming flower, becomes wilted, imprisoned by the wants of her father and the expectancy of her hand in marriage. The film aches with a poignant melancholy as Kaguya’s father steals her away from the rural surroundings of her home, forcing her into the city - the foray of high society - where the attempts to win her favour come in spades. She longs for a return to the country - the endless fields of bamboo stalks, the running streams and tactile mud - and thus, rejects all her prospective suitors accordingly. Finally, when the Emperor of Japan, allured by her beauty, proposes his hand, she refuses him also; divulging to her parents that she is a child of the moon and that that is where she must return.

Evoking an idealistic acclamation for freedom in a world strung together by political systems of status and capital, Takahata’s Kaguya is a vibrant allegory of man’s propensity toward ownership; particularly with regard to women. Kaguya is found amidst the bamboo, seemingly grown from nature, and yet, her father believes she belongs to him. Later, when she refuses the Emperor’s marriage proposal, he responds with violence and obsession, asserting that she must be his by organising an army of soldiers to steal her away from her home and family. These men, these institutions of control are convinced that Kaguya - this angelic being born of bamboo - is but a pawn in their want for political and monetary gain. To this extent, the father is near-correct, as Kaguya’s happiness seems to breed treasure and wealth in the film’s first act. The bamboo plants of her origin begin to manifest gold, rich linens and expensive embroidery; causing her father to insist that she should lead a life of leisure and royalty; the only path there however, is through marriage and exhibition. Yet, as Kaguya is thrust further into the realm of nobility, her melancholy extends and the gifts of her jubilation diminish.

Kaguya’s happiness is key to her magical powers, those of which duly fade as she continues to rebut her father’s potential suitors. The princess is freedom incarnate, and as such, when thwarted by systems of oppression, restraint and possession, she yearns for escape; to return to the boundless idyll of the countryside, and failing that, the mystical paradise of the moon. With Kaguya, Takahata intended to create a more empathetic character than that of the Nayotake no Kaguya-hime ["Shining Princess of the Young Bamboo"] of the original text; an end he meets fervently with this poignant retelling of the allegorical Japanese folktale.

A transcendent effort which proves forthright the capacity to tell mature stories through animation, as well as Takahata’s incredible artistic skill and poetic mastery, Kaguya is an utter triumph of poignant storytelling and an appropriate swan song to the director’s illustrious career in anime filmmaking.

The Red Turtle [or Isao Takahata’s Encore]

While Takahata wouldn’t go on to direct any more films in the 5 years between the Japanese release of Kaguya and his untimely death in 2018, the acclaimed anime filmmaker would enlist his help with the dream-like masterpiece, The Red Turtle [2016] by Dutch animator Michaël Dudok de Wit. Following the story of a man who inexplicably becomes shipwrecked on a deserted island, the film explores the ephemeral reality of life, love and the beckoning notions of ageing and death. As the man struggles to escape the confines of the island, he is repeatedly stopped by a mysterious red turtle, and as his resilience turns to rage, the film drifts into a wholly unexpected, and utterly mesmerizing turn of events.

Serving as an artistic producer for the French-Japanese animation, Takahata’s presence can be felt throughout the piece, with its propensity for cute, personable animals and its penchant for environmentalism. Moreover, the film seems interwoven with Takahata’s resonant notions of isolation and his use of narrative stillness, as the characters speak with little to no dialogue while the crashing waves and stylistic dream sequences speak volumes.

Citing film critic, Mark Kermode of The Guardian, The Red Turtle is informed by the “rapturous minimalism [of] Studio Ghibli” and as with many of the animation house’s masterpieces “transcends boundaries of language, culture, geography and age [... with its] minimalist visuals [... and] nursery rhyme candour”. It is a pensive encore to the eclectic array of animated masterpieces to which Takahata would lend his creative genius and a delicious watch for the eyes as well as the soul.

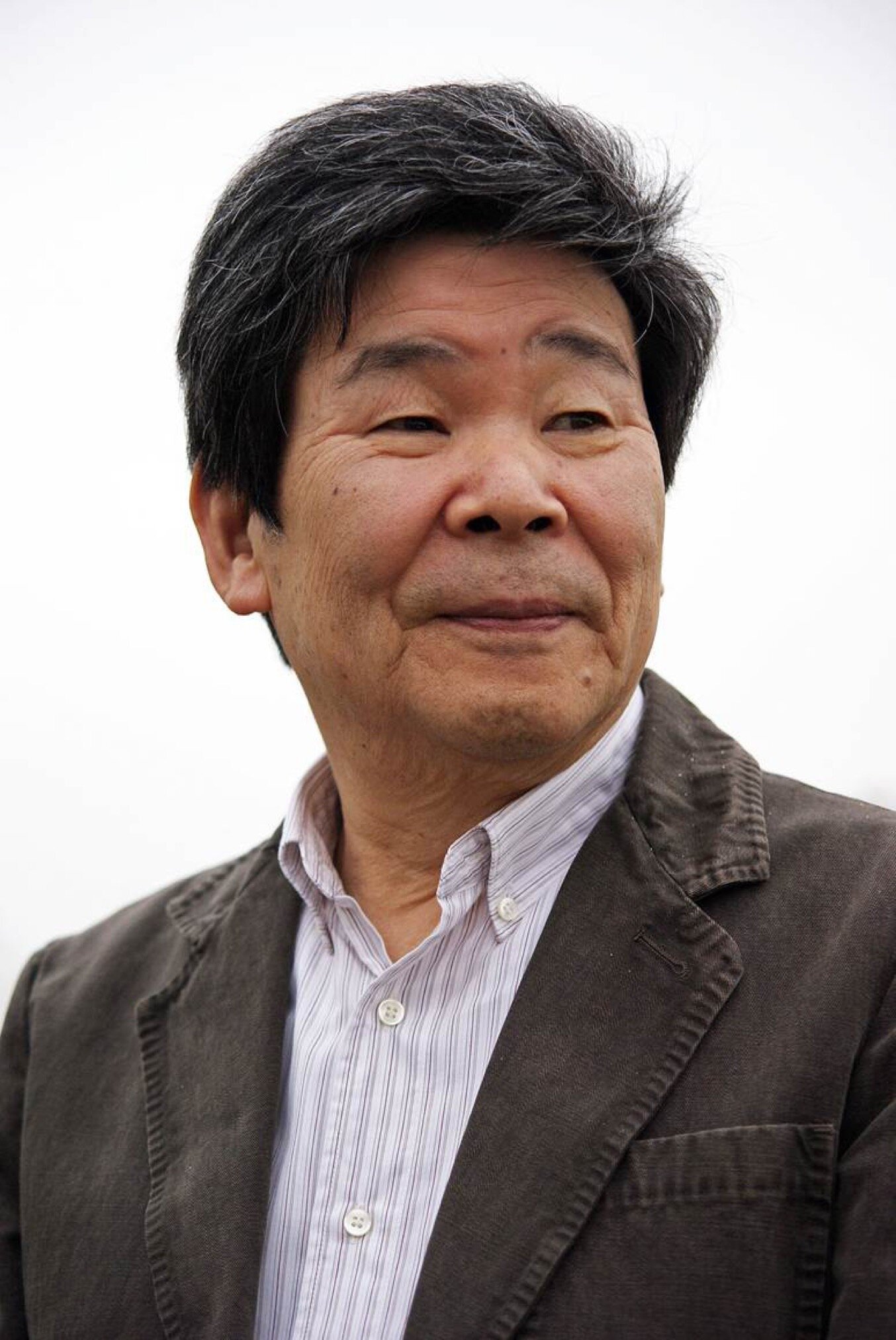

Paku-san [1935 - 2018]

After being diagnosed with lung cancer, Ghibli’s co-founder and the creator of many of its breath-taking works, died on April 5, 2018, at a hospital in Tokyo, at the age of 82. Eulogized at a ceremony at the Ghibli Museum in Tokyo, Takahata received his due recognition for being a leader in Japanese animation and was lauded by fellow Ghibli founder and life-long collaborator, Hayao Miyazaki as the man he could trust the most despite their somewhat turbulent working relationship.

Recalling the time he met Takahata 55 years prior to his death, Miyazaki affirmed that "[he] was convinced that Paku-san [Takahata's nickname] would live to be 95 years old, but he unfortunately passed away”. Holding back tears, the renowned anime filmmaker bid farewell to his friend and colleague, in an admission of brevity that we reiterate vehemently: “Thank you, Paku-san”.

About The Author

Simon Jenner explores meaningful storytelling through film and media, occasionally producing a little writing along the way.