Questions of identity: Yohji Yamamoto through the lens of Wim Wenders

“… sometimes I am shouting in my mind, I am not a fashion designer, I am a dressmaker!”

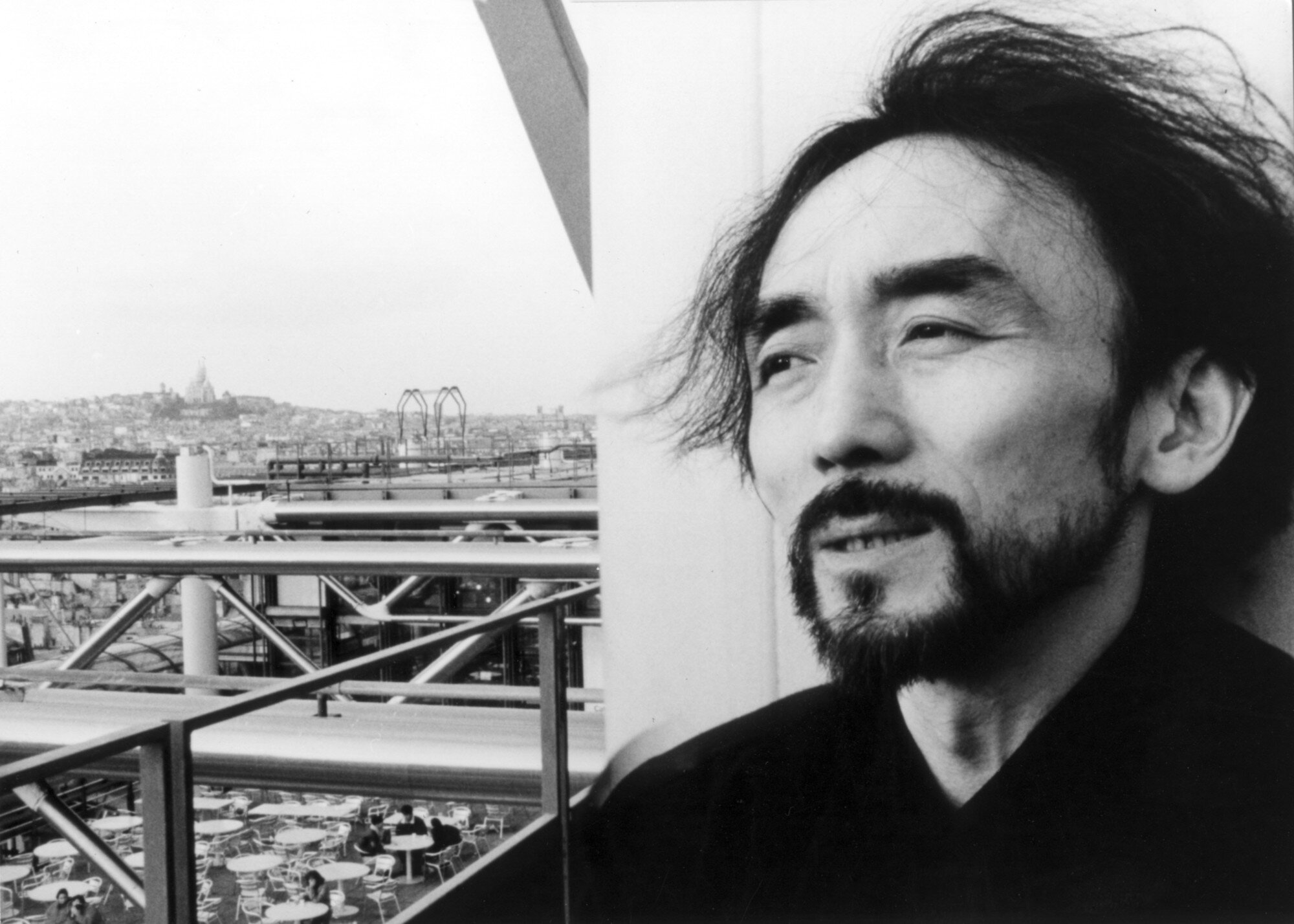

In 1988 two master artisans met for a series of interviews in Paris and Tokyo. Both of them were exploring the nature of form, both of them wavering between their well-known, refined techniques and the urge to break free from a prison of formalized style. Wim Wenders was not interested in the apparel business nor did he want to take the whole hoopla surrounding it seriously when he was invited to make a short film about the fashion world by the Centre Pompidou. What made him take a shot at the project after all was the chance to meet Yohji Yamamoto and an opportunity to examine possible similarities between two fast-paced industries: cinema and fashion.

Everyone who expects to watch just another entertaining behind-the-scenes documentary of fashion collection X in year ‘XX with short interviews of seamstresses, gangly models, stressed out PR reps, etc. should most likely avoid this piece of filmmaking.

Since its release in 1990 the essayistic documentary “notebooks on cities and clothes” has undoubtedly become an essential reference to Yamamoto’s dressmaking. But even more so it throws the viewer right in the middle of a philosophical quest for identity – a main theme for the works of both grand masters interacting here. What constitutes identity? What do the clothes we wear say about us? How do they make us feel? Are they helping us to [re]produce an image that we have about ourselves? Do they allow us to feel like we know where we belong?

These are the leading questions for this trip guided by Wim Wenders’ voice-over narration, interspersed with interview sequences with Yamamoto as well as cityscapes of a Tokyo that doesn’t exist any more. As it is typical for a Wender’s production, the viewer has to be ready to explore the film, which slowly takes shape over the course of the roughly 80 minutes. You embark on a diary-like expedition with the director, delving into his thought process. Some critical voices have deemed the strong presence of the director himself in this movie a “narcissistic” move – god knows what they expected from a documentary about fashion.

For Wenders the philosophical journey began after his first encounter with the brand Yohji Yamamoto when he had purchased a shirt and a jacket long before he even had the invitation to do this film. What immediately caught his attention was the way the clothes made him feel and what they mirrored back at him, which was so much more than just the regular excitement about a new look. In the film he recalls it as an experience of identity.

“This shirt and this jacket… it was different. From the beginning they were new and old at the same time. In the mirror I saw me, of course, only better – more me than before [...] a shape, a cut, a fabric – none of these explained what I felt. It came from further away, from deeper. This jacket reminded me of my childhood, and of my father, as if the essence of this memory were tailored into it – not in the details, rather woven into the cloth itself.”

How could a Japanese weave this heartfelt nostalgia into fabric, when, as the movie recalls, Western clothing had only been around for about 100 years in Japan at the time of filming. Wenders finds his answer in Yamamoto’s studio: photographs and images from different decades, different countries, famous faces, no-name people and books … tons and tons of photo books, scattered all over the place, stuffed with post-it notes, almost bursting at the seams.

Amongst the collection Wenders quickly discovers a photobook that he also holds dearly: People of the Twentieth Century by August Sander. Starting in the 1920s the compilation spans over 40 years of Sander’s work documenting German society. In it are hundreds of black-and-white portraits of citizens who were then neatly categorized by social type and occupation, even including marginal groups such as “gypsies” and the unemployed.

These visual memorabilia are a main source of inspiration not just for Yamamoto but also for Wenders. Dressmaking, filmmaking and identity then might well be an aggregation of memories, events and techniques from the past. They seem to be in harsh contrast with the present and its fast-paced modern life. Yohji doesn’t fail to point out how people in modern cities appear to be a faceless, indistinguishable mass of people mindlessly consuming fashion and even their lives. With his father having passed away during World War II, he had grown up with a mother who was a dressmaker herself. So he was surrounded by strong women that customized clothes with their own hands to make them fit their client’s body and their reality. In Sander’s photographs he clearly admires the strong connection between the depicted individuals and their looks:

“Real-life people, in real clothes; no consumption; the people wearing the reality [...] not the clothing, but wearing the reality. In there, there is my kind of ideal of clothes. Because people don’t consume the clothing. People can live life with this clothing. I’m especially curious about their faces, because of their career, life and business. They have the exactly right faces for that, I think. So, I’m admiring their faces... and clothing.”

Yamamoto and Wenders both seem fascinated, if not obsessed, with craftsmanship and work created by human hands – the filmmaker with his love for celluloid film instead of the emerging digital technology and the designer with his approach to clothes always starting from fabric, material, and touch before considering forms and shapes. Wenders succinctly summarizes Yamamoto’s hands-on process when creating a new dress: stand back, look, approach again, grasp, feel, hesitate, sudden activity, a long pause. A dance of hands giving shape to his ideas and his identity as a dressmaker.

Things take an interesting turn though as it becomes clear that this identity of his has indeed become a trademark, something he needs to be able to exactly reproduce over and over again for the sake of his brand and his design language.

There his art and identity rather start to appear as an ongoing process, as a quest for balance: between clothes that are “new enough” and “classic forever”, between “remaining the author of his ideas” and “being a prisoner of a distinctive form language he established”, between being a singular Tokyoite versus being installed as a representative for the whole Japanese nation by foreign fashion journalist.

This never-ending process of framing his unmistakable identity is captured in a key scene of the movie: for almost 2 minutes we watch Yamamoto adding his handwritten signature to a renovated store – writing, erasing, rewriting, erasing, reproducing and casting his identity into letters as he must have done numerous times before that.

Besides these precious insights into Yamamoto’s creative process, fans of meta level storytelling will definitely appreciate the internal struggles of Wenders himself which he not only expresses in the voice-over but also in the visual concept of the movie. He seems caught between his adamant love for celluloid film and the opportunities offered by a then new technology – video, which he deeply despised calling it the means of “democratic amateurism” and mediocrity as opposed to classic, high-quality filmmaking.

Early on he realized, however, that his small video camera seemed to be more suitable than his noisy, slow 35 millimeter movie camera to capture Yohji's work in real time. The video camera was always ready, unobtrusive, spontaneous, and free of the corset of formalities created by 100 years of celluloid film history. This “parallel storyline” explains why a lot of the scenes are collages, for example of film in the background, a TV screen with scenes from the atelier and Wenders’ hands holding a handheld video camera depicting interview sequences. Yet another dance of hands.

This article only touched upon a small fraction of the “notebook on cities and clothes”, so it’s definitely worth watching and diving deeper into the creative process of Wim and Yohji. For everyone who still can’t get enough of Wenders’ discourse on identity and craftsmanship, there’s an excellent collection of essays and interviews by him: THE ACT OF SEEING – TEXTS AND CONVERSATIONS [English edition released in 1997, German edition in 1992].

Text by: Jennifer Duermeier