The Democratisation of Fashion: How Bonne Suits is Changing a City

In 1952, at the gathering of the first World Humanist Congress, The Amsterdam Declaration was formed.

This, in an era of Cold War and political chess, revolved around one primary principle: that whatever issues the world was facing could be overcome. The Amsterdam Declaration was an assertion of hope - it signified belief in the fundamental good embedded in humankind.

There’s a reason such a monumental declaration took place in Amsterdam, and more broadly, the Netherlands. Perhaps it was more of a self-fulfilling prophecy: the country that catalysed a declaration of hope, equality, ethics and social responsibility had no choice but to become that which it pre-supposed.

It is in this country that the founder of Bonne Suits - Bonne Reijn - grew up. Born and raised in Amsterdam, Reijn owns a brand that is about far more than suits: it is about democracy and empowerment. When you think of a suit, the natural inclination is to think of the City Boy, the Salary Man and often, the over-inflated Ego. Reijn wants to dissociate the suit from these archetypes. He wants the suit to stand for the virtues of the Everyman: the relatable character that embodies us all. All of our fears, our courage, our fallibility; Reijn wants to re-democratise the suit for the Greater Good.

“100 years ago”, Reijn reflects, “the normal attire was suits. Farmers, cooks, beggars - people with money and without it - they all wore suits”. Reijn wants the suit to return to its utilitarian glory. Currently stocking two core ranges [the classic Bonne Suit, double-breasted with four outer pockets, and the De Rrusie - a slightly more elegant, Parisian variation, designed in collaboration with Reijn’s dear friend De Rrusie, from where the suit derives its name], Reijn knows that in today’s climate, an androgynous suit made of hardy cotton is a statement.

Self-dubbed “the poor man’s suit”, Bonne Suits summarises an approach to fashion as well as a worldview. Reijn has spent his life working in fashion [his introduction was a job at Amsterdam’s prestigious SPRMRKT in 2007, with a move to Patta six years later when he was 23] and he harbours less than positive views, citing a frustration with the fashion world’s elitism, and the false idols of beauty and wealth. Reijn argues that fashion should be accessible for everyone.

Bonne Suits’ first product was the self-titled Bonne Suit, which launched in 50 all black and 50 all white, directly from Reijn’s front room. These sold out instantly, and Reijn used the funds to launch the webshop with the help of his friend Justus Cohen. At this time, Cohen joined the team and helped Bonne Suits solidify into a fully fledged business. [Cohen now owns 50% of Bonne Suits, and in Reijn’s words, “does all the business stuff”.] Reijn’s cult personality, which started taking shape during his time at SPRMRKT, where a 6ft broad shouldered cis-male excelling at styling stuck out like a sore thumb, propelled his brand to cult status in Amsterdam.

Around the time of the first launch, Reijn and his friends, the elusive SMIB Collective - who forged a reputation as Amsterdam’s primo hip hop crew spinning music from SpaceGhostPurp, Raider Clan and the like in 2015, and playing cult shows at OCCII, a self-run, low-key, music-lead venue - could be spotted sporting Bonne Suits whilst DJing, and in music videos such as Gucci Louis Polo Prada. Whilst Reijn laughs over the phone, asserting “that was a long time ago”, the influence of his past projects in building a following can’t be understated.

Reijn’s proclivity for socialising, coupled with the fact he was born and raised in Amsterdam, means he is a key figure in the Dutch creative scene, and he uses this to the best of his ability: to put his friends on. “I want the suit to be both a statement and a blank canvas”, Reijn muses when reflecting on the Artist Suits range - a collaborative effort where artists can give “their own interpretations of [our] suits in full freedom of creativity”.

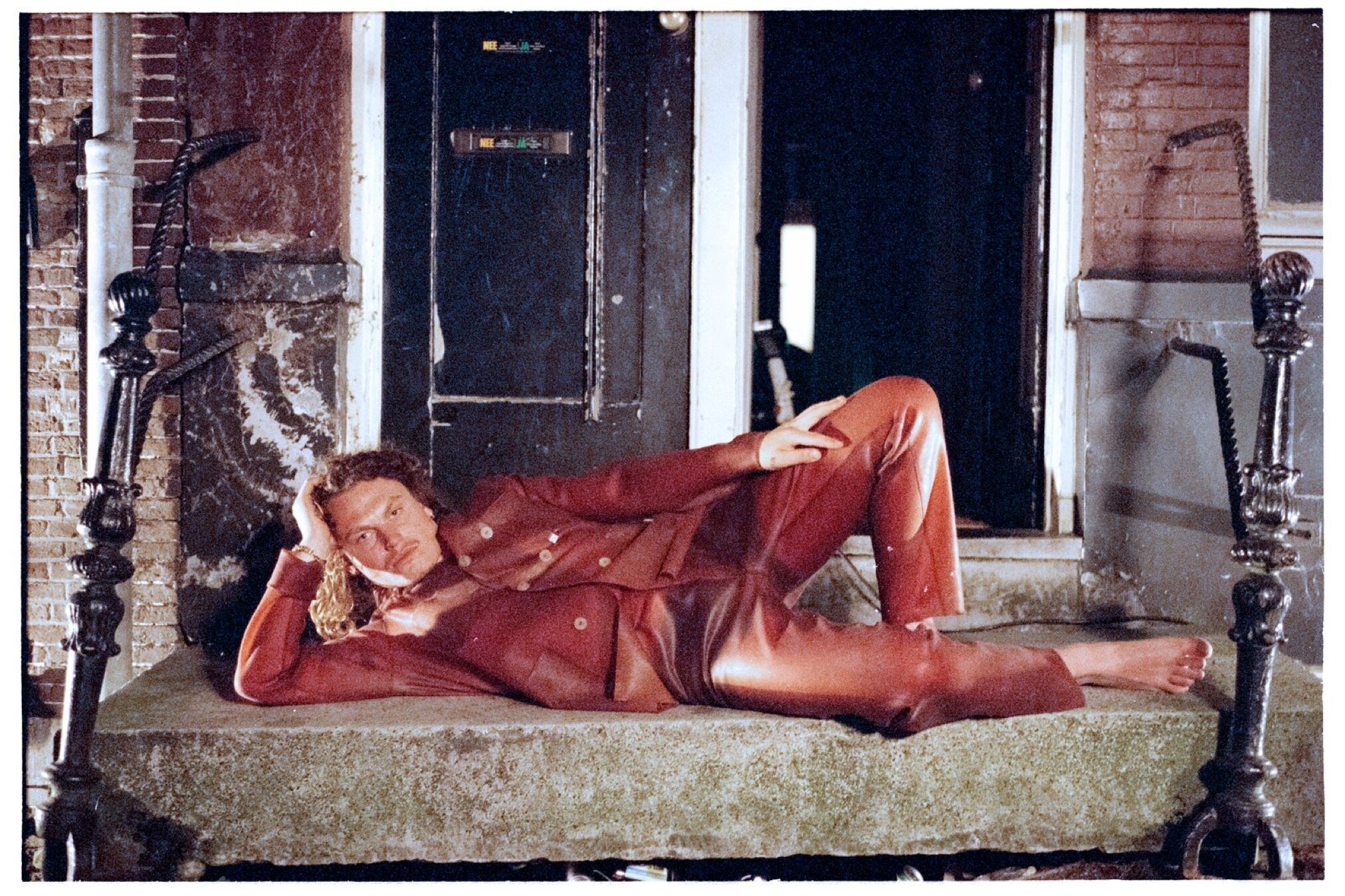

To this date, Bonne Suits have been tie-dyed, painted, airbrushed, stitched, embroidered and bleached; the usual 400 gram/sq metre cotton has been subbed out for discarded denim, kimono fabrics, knitwear, latex, leather and nylon. What started as a way for Reijn to bring his friends into broader collaborations, has become a subheader for the brand’s collaborations in general, with the leather suit as part of the Bonne Suits X Ecco Leather collab, and the nylon suit an extension of Bonne Suits’ second collaboration with Patta [the first featured Patta’s P monogram printed all over the entire suit]. Importantly, the artist's intention must echo that of Bonne Suits, with special emphasis given for the use of discarded materials, upcycling and reworking.

When asked about any plans to extend the core range of suits to include any of the popular runs, for example a nylon suit, Reijn was dismissive. “What’s nice about the collaborative runs”, Reijn says, “is that it encourages innovation. My friend, a graphic designer called Gilles de Brock, built a new painter in order to airbrush on clothes”. Reijn is thankful for the lengths that people have gone to produce adaptations of his suits, and wants to keep them as limited runs, allowing his brand to shine with a variety of reworks whilst maintaining a humble core.

During our phone call - where Reijn is stretching his legs in a woodland outside of the city - he gives an astute critique of both fashion and society: “the problem”, Reijn goes on, “is that when something involves a hierarchy, it makes someone above someone else. This is especially obvious in fashion, where people are put on pedestals. I want to bring everyone back to the same place”. Drawing an analogy that could’ve gone sour, I ask if Reijn’s egalitarian intentions, and the similarities between Bonne Suits and that of those worn by people during the Maoist regime is a coincidence. “Aesthetically, the suits are based on that of many European farming people. But the utilitarian nature is there. You could paint, cook or do manual labour in these suits. That’s the level playing field I’m talking about”. [A week after the phone call, the description for the new Daily Paper x Bonne Suits collaboration explicitly references Bonne Suits’ “proletariat roots”.]

Bonne Suits isn’t just talk, either. The brand has made a home for themselves at Zeedijk 60, on a street in Amsterdam that used to be associated with crime, prostitutes and drug dealing. Pioneering a regenerative initiative on the street, whilst maintaining the street’s propensity for diversity and avoiding harsh displacement, Bonne Suits joined forces with fellow clothing brand The New Originals, and SMIB-affiliated brand SUMIBU, to create a store and creative force in the heart of Amsterdam. Reijin is confident that this isn’t a negative form of gentrification: “the street wasn’t residential” he says, “so we aren’t evicting anyone. It’s a safer place for tourists and shoppers”.

Having built a good reputation with the local council for their efforts, Reijn hinted at the prospect of opening a bar or restaurant on the street, but admitted that covid has delayed any plans. “The council wants us to continue to build the area, and we’re happy to do it because it means we have a hold on how Amsterdam changes”.

With accessibility at the core, it’s also no surprise to hear that the art exhibitions Reijn holds at his house revolve around the same premise. “We want to give back to the city, but also stick it to the Man”, he says. The art gallery, run under the name Gallery de Schans, encourages expression and accessibility whilst eschewing elitism. The gallery works closely with the Gerrit Reitveld Academy - Amsterdam’s leading art school. They hosted an end of term exhibition with work from the class of graphic designer Vincent van de Waal [Patta’s in-house designer], in addition to looking abroad for curation, where they open up the gallery to wider groups [for example, they hosted US Intimacy Op de Schans - a series of four female-lead exhibitions focusing on gender identity and vulnerability, curated by Zippora Elders]. When the art is for sale, much like the suits, it is priced affordably so that “normal people have access to it too”.

Bonne Suits’ influence doesn’t stop at the city limits. Over in Rotterdam, the brand has been in discussion with a museum to design their uniforms, and in Korea, the brand was approached by a barbershop to do the same. After the Korean Barbershop received the suits, they replied by sending humorous video snips of themselves kidnapping people with bad hair and sorting their trim. Reijn adds - nonchalantly - that they also designed the uniform for the opticians at Ace & Tate [“Who are the eye guys in Ace & Tate? Yeah, we do their uniforms too”].

Whilst Bonne Suits is well solidified as a brand, with stockists all over Europe, Asia and the US [Reijn cites Opening Ceremony in NY and LA as one of their most successful stores], the brand is really about more than suits. Reijn has used the suit as a vehicle for a commentary on society at large. By mobilising the efforts of his friends and peers through fashion and art, Reijn has taken a blank canvas and imbued it with voices, like hundreds of tiny, lively brush strokes spread onto a sea of white.

The poor man’s suit: an affordable, utilitarian and androgynous suit that doesn’t look out of place covered in grass stains, paint, or covered in specks of wine at a wedding. A brand that manages to capture a city’s liberal and democratic core, in conjunction with a man who has intentions of giving back to the city that raised him. If the story of Bonne Suits is anything, it is a love story to Amsterdam, and a testament to the city’s creative scene. If Bonne Suits was around in 1952, they would’ve been asked to design the uniform for the World Humanist Congress, too. There’s no suit more appropriate to sign The Amsterdam Declaration in.

About the author:

Jacob is a chef and writer based in Manchester, England. He specialises in environmental consultancy relating to food and fashion.