A Cinematic Trip: Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets

A hit for Japanese New Wave film buffs, Sho O Suteyo, Machi E Deyou (Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets) directed by Shuji Terayama is a lengthy experimental movie critiquing Japanese society in the 1970s.

A burning American flag, a penis-shaped punching bag in the middle of Tokyo, and a stuttering monolog, Terayama included it all in his 1971 feature-length film Sho O Suteyo, Machi E Deyou (Throw Away Your Books, Rally In the Streets). In a provocative fashion, this movie questions the place for individuality in a society that prioritizes conformity.

Shuji Terayama was born on December 10th, 1935, and grew up in the prefecture of Aomori, Japan. His childhood was turbulent since he grew up during World War II and lost his father in 1945. As Japan progressed into its post war period, Terayama found interest in literature, theater and avant-garde art. He was successful as a writer, a poet, a theater and film director, as well as a photographer, known for his politically proactive and experimental oeuvre. With a legacy of over 20 films and nearly 200 pieces of literary work, the artist passed away at the age of 47 due to health issues in 1983. Posthumously, a museum in Aomori was built in his memory in 1997.

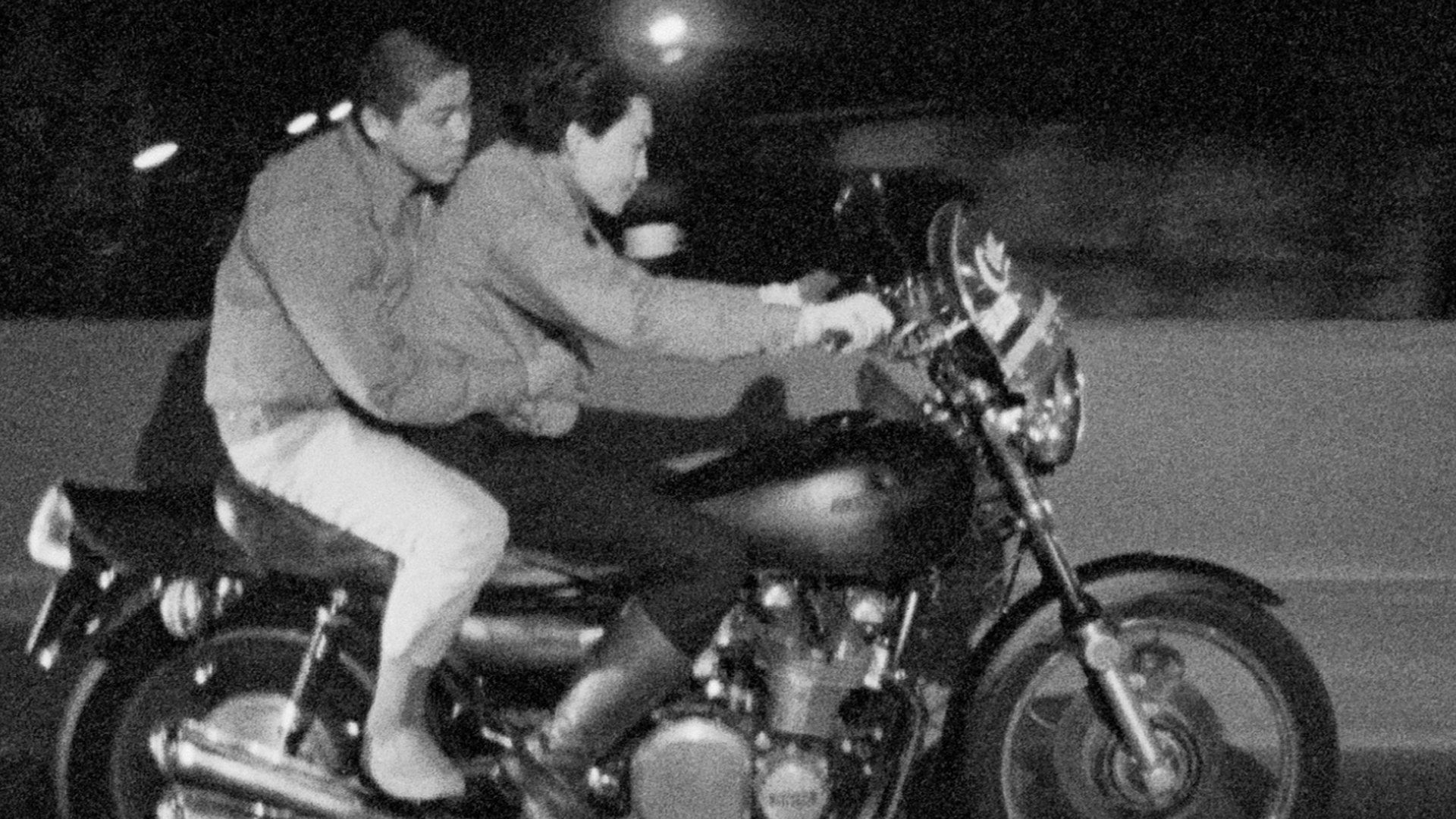

The main character of this film, a teenage boy growing up in the poor outskirts of Shinjuku, remains nameless. We follow him throughout the movie as he desperately tries to shake off his boyhood and poverty, in order to find some kind of meaningful life. The camera hits the streets, with interview-like scenes of sex workers, or men who are searching for companions.

The boy navigates his difficult relationship with his broken family, whether it be his sister who is unhealthily obsessed with her pet rabbit, his unreliable perverted father or his grandma, desperate to not be sent away to a nursing home.

His disillusionment, his tumultuous sexual initiation and his personal dilemmas are a reflection of the issues within youth culture during the political and economical upheaval of the 1970s. Unlike any coming of age movie, Terayama perfectly conveys the theme of self-liberation.

The plot is far from a traditional three-act structure. Terayama’s unique approach to films is characterized by how he jumps from one point of view to another, blurring the line between the character’s mind and sight. The visuals are fast, brutal and bizarre, with the camera swinging and spinning, transitioning from one room to the other.

Extremely experimental and surreal, this film is one of the most confusing and maximalist in its genre. The 70’s trippiness is not subdued, with scenes tinted sepia green and mauve, as well as drawing inspiration from Russian poetry and Noh theater. In addition, this feature-length film reaches out to the audience by breaking the fourth wall, mixing a documentary-style approach to a fictional storyline.

Voted in the top ten best Japanese movies of the year 1971, the soundtrack remains as one of the most outstanding elements of the movie as well and is a mix of Japanese folk songs with odd lyrics or full-fledged rage translated through psychedelic rock tracks. Sho O Suteyo, Machi E Deyou presents eccentric yet incredibly humane characters because Terayama puts emphasis on their flaws and vulnerability, touching themes like desperation, desire and uncertainty. They all remain somewhat anonymous, in order to remind the audience that each person has their own perception of reality and are trying to find themselves within the masses.

Sho O Suteyo, Machi E Deyou is partly a critique of the widespread of American culture in Japanese society and the clash between those two. The gap between generations on their contribution to the integration of Western ideas is portrayed by the various characters, ranging from teenage boys to lavish prostitutes. Additionally, the culture around sexuality and its deep link to boyhood and girlhood equally are discussed in this film, with disturbing scenes of sexual violence and an aura of promiscuity throughout the movie.

This puts a lot of focus on the sexualisation of women in Japan at that time, in parallel to the uprising feminist movements, and the normalization of this duality. As well as diving deep into cultural issues, this movie examines the roles of people in order to have a functioning society, like motherhood in relation to the patriarchy, and the rejection of authority by teenagers.

As the characters blast out the pitfalls of humanity, Terayama captures the selfishness in survival, the ups and downs of grief and the secretiveness of shameful, intrusive thinking.

A shocking cinematographic masterpiece, the film does not miss out on an omnipresent feeling of anarchy and revolution, typical of the 70’s hippie ideologies and the many protests in Japan in the late ’60s.

Disclaimer to the viewer: this film contains sexual violence, animal violence, vulgar language and nudity.

About the Author:

Mizuki Khoury

Born in Montreal, based in Tokyo. Sabukaru’s senior writer and works as an artist under Exit Number Five.