The Legacy of Super Smash Bros. Melee

Super Smash Bros. Melee; a party game, a fighting game, an anomaly.

From its initial conception after the success of its 1999 predecessor, Super Smash Bros. for the Nintendo 64 - the flagship crossover fighter, which brought together Nintendo characters from across the gaming spectrum - Melee was developed to combat the endless array of competitive fighters which had become the genre norm since the 90s.

By simplifying attacks to single button inputs, and incentivising party-style multiplayer via the inclusion of in-game items, stage hazards, and large-scale maps, series creator Masahiro Sakurai, intended to tear down the boundaries set by gaming royalties such as Tekken, Marvel Vs Capcom, and Killer Instinct; enabling casual players to brawl it out with their favourite gaming icons, without the restrictive chain combo systems of these earlier titles.

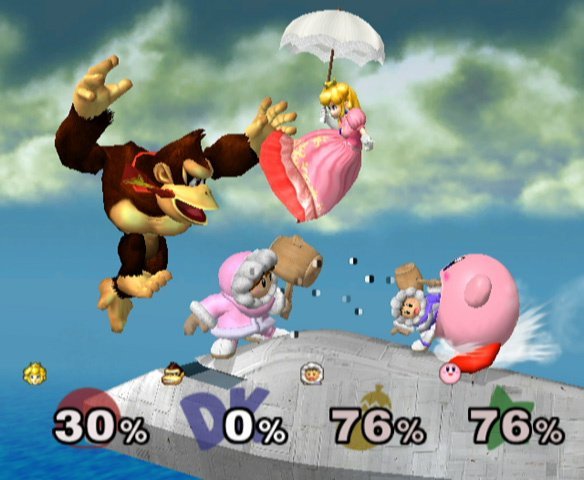

Unlike most fighting games, Melee characters sport notably smaller move-sets, encouraging players to string their own combos together instead of having to commit to the built-in, technically-intensive ones of series like Mortal Kombat. Instead of fighting side-on in intimate one-on-one arenas, Melee offered larger scale maps, randomly generated items and the ability to play with four players at once. And rather than having a diminishing health bar, players build up a percentage based on the damage they’ve taken; the more they take, the easier it is to hit them off stage and into the dreaded blast zones [the perimeters of each map].

Developed by Hal Laboratory, the original Super Smash Bros. was initially developed as Dragon King: The Fighting Game: a 3D prototype with faceless humanoid characters that was created to experiment with the Nintendo 64’s unique joystick; contrary to the console’s other star titles, Super Mario 64 [1996] and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time [1998], which instead made use of the analogue stick. In an instalment of Iwata Asks, with the late Satoru Iwata, Sakurai explained that he intended to create a “4-player battle royal” that “offered a new experience every time you play”, allowing a greater degree of player expression than most fighting games of the era.

“Nowadays, we take it for granted, but at the time, people had reservations about mobilizing an all-star cast of characters” [Iwata, Nintendo].

Yet, despite initial trepidation, the game proved a hit, selling over five million copies worldwide; validating Sakuari’s idea to bring together gaming heavyweights from across Nintendo’s extensive roster of iconic characters, and establishing the series’ trademark fighting style to boot.

“We were put through the wringer alright”, affirmed Sakurai to Iwata, and came out brawling, establishing a game that has since become an icon of the fighting genre and proved an appetite for more in the same vein. Speaking to 1UP in 2010, Sakurai illuminated upon how the runaway success of Super Smash Bros. propelled his team to develop a sequel which not only capitalised on the original’s achievements but also explored the potential of bringing in new characters, new ideas, and the prospect of developing for the infant GameCube, Nintendo's first optical disc console.

“I seriously felt like a man on a mission. [...] With Melee, though, the previous game did well enough that Nintendo and the character designers knew what I wanted in advance. And I wanted a lot. It was the biggest project I had ever led up to that point, and I was bearing the burden of many historically important video game characters on my back. It was the first game of mine on disc-based media, the first that used an orchestra for music, the first with ‘real’ polygon graphics. My staff was raring to go, and we plunged in full-tilt from the start” [Source Gaming, 2015].

In just thirteen months after the release of Super Smash Bros. Sakurai and team achieved just that; delivering a game that not only improved upon every facet of the original - including fourteen new characters, a whopping twenty-nine stages, tightened controls and better graphics - but ignited a new era in competitive fighting games.

In 2001, Melee was born, and, as with the series original, “was supposed to be the antithesis to how hardcore-exclusive the fighting game genre had become over the years” [Source Gaming, 2015]. The result of course was something entirely different. In the years after its release, Melee nurtured a small community of players who felt that, despite Sakuari’s original intention, the game was poised for competitive play; incentivising the creation of local tournaments in both the US and Japan. Pioneering smasher, and progenitor of the Ken Combo, Ken Hoang, discussed his origins in the community; elucidating to Polygon how the competitive scene for Melee grew naturally out of the collective determination of the player base, and the guerilla-style tournaments of its early days:

“My first tournament was at a local game store. It was a free-for-all tournament with items on, which was crazy; you’d never see that today. The event itself was unusual back then. Since I hadn’t heard about any Super Smash Bros. tournaments happening in the wild, I didn’t even know they existed. Once I went to my first one, it was like the first time I ate ice cream. It felt like home” [Hoang, Polygon].

This was the beginning of what was to be a revolutionary feat of community engagement and player-driven proliferation, with players taking it upon themselves to generate rules, and expose new players to the magic of Melee. Four stocks (lives), eight minutes, items off, and only a specific selection of “legal” stages to be played at a competitive level.

Players began to explore the game’s famously extensive meta, discovering the cracks left due to its rushed development cycle, and discovering glitches, exploits and imbalances which would lay the foundations of Melee’s competitive edge. Fox’s incredible speed has generally kept him at the top of Melee’s character tier list, while Kirby’s slow movement, low airspeed, and ineffective projectile attack, Final Cutter, lands him firmly at the bottom.

Further exploration of the game’s meta includes the dissection of the game’s frame data, with players devoting their time and effort dissecting character hitboxes, and uncovering new techniques at every turn. There probably isn’t a member of the Smash community who hasn’t heard about wave dashing, let alone the short hop fast fall L-cancel [otherwise known as the “SHFFL”]. Melee is a game with tremendous depth and a community driven to analyse every morsel of data, every combat style, and every blast zone with the sole purpose of getting good and ensuring your peers get good also. I used to main Captain Falcon back in the day and enjoyed long moonwalks across Battlefield, ledge-cancelling all over my opponent, before eventually getting gimped by its awkwardly angled underside. Although I've since fallen off the Smash bandwagon, the community continues to grow, bringing in new players and expanding the game’s meta exponentially.

It was this curiosity for Melee’s exhaustive meta that led to a steady increase in players who saw the game as a way to express themselves through gameplay; creating their own distinct play styles through movement, combat and attitude. Like a brush to a canvas so to speak, wherein the artist is the player, the character the palette and the moves the paint.

As the player base grew so did the competitions, with esports organisation, Major League Gaming [MLG], picking up the game in 2004 and hosting the biggest tournaments the community had ever seen. Until 2006, MLG streamlined the explosion of Melee, offering actual cash prizes and eventually forming the game's first competitive circuit. Melee began playing alongside esports heavyweight, Halo, and streaming matches online for the first time, bringing a slew of legendary players like Daniel “Chudat” Rodriguez, Christopher “Azen” McMullen, Joel Isai “Isai” Alvarado, Daniel “KoreanDJ” Jung, and Jason “Mew2King” Zimmerman.

“[MLG] held the only tournaments with good money in Melee. A $2,500 prize pool for each event. [...] The events felt different. They had these bars behind each TV. It was like a wrestling ring-type thing that kept others a good distance away from you” [Zimmerman, Polygon].

This set in motion what the community refers to as “The Golden Age of Smash”, in which, between 2004 - 2008, MLG brought competitive Melee to the masses and showed no signs of slowing down.

In the years after its release, Melee would battle its way to the top of the fighting game tier list and forego Sakurai’s original intention by “becoming [the] Smash Bros. game for hardcore fighting fans” [EDGE Magazine, 2014]; even inspiring two industry-standard documentaries from filmmaker, Travis “Samox” Beauchamp.

Yet despite its optimistic beginnings, the history of competitive Melee is thwarted by hardship, controversy, and endless legal battles. From the early days of lifting clunky CRT TVs down to someone’s basement for a local tournament to the grand slam of APEX 2015, the first fighting game tournament to bring all four Smash Bros. games together, Melee has been through the dirt; with the community suffering major setbacks due to Nintendo’s reluctance to licence the game at many major tournaments.

With a backlog of complex legal disputes, Nintendo has often been regarded as withholding accessibility to games under the pretence of their, somewhat pretentious, seal of quality; differing from other major gaming giants by restricting their games to be made playable solely on their hardware.

This has somewhat mirrored the way in which their games are hosted, or in this case, not hosted at many esports events. Smash is probably the best example of this restrictive business practice, with the company failing to support the growth of Melee within the competitive gaming scene. Another argument is that the explosion of competitive play within the community went against Nintendo and Sakurai’s original intention for Melee to be a casual party game. Aptly expressed by Hugo Blair of University Express, “a competitive scene was not something on the developers’ minds during creation; the game as envisioned by Sakurai was designed to be played as a casual party game”. Thus, when Melee started to pop off, and garner traction with organisations such as MLG, and tournaments such as Genesis, Nintendo were quick to try and prevent the game’s off-brand exposure; most notably when the company tried to block the streaming of the game at Evolution Championship Series [EVO] 2013 under the pretence of copyright infringement.

“Melee made it to Evo, and Nintendo tried to prevent it from happening. Everyone, and I mean everyone, was just wondering why they did that. It was a crazy thing to happen” [Nairoby “Nairo” Quezada].

Even despite the community winning a charity drive - raising $94,683, and beating out Skullgirls [$78,760] and Super Street Fighter 2: Turbo [$39,567] - for The Breast Cancer Research Foundation to secure Melee a place at the event, Nintendo still tried to block its admission; with no established claims to behold other than the pretence that it was their IP and they could do what they want with it. This had the opposite effect, however, with the community bending over backwards in support of the game on social media and eventually getting Nintendo’s claim upturned. Thereby, allowing Melee to stream as intended.

Since then, Nintendo has continued to wrestle with the community about the game’s place in fighting game tournaments, culminating in an instance prior to The Big House 2020, in which the video game giant sent a cease and desist letter to the tournament’s organisers, preventing the use of newfound matchmaking software, Slippi, from being used for online play.

Created by Jas “Fizzi” Laferriere in 2018, Slippi was a revolutionary feat in the history of Melee, allowing players to battle online with little-to-no delay by way of the open-source video game console emulator, Dolphin. Up until this point, Melee could only achieve frame-perfect data by playing in person, using a CRT. Otherwise, players had to use Dolphin netplay, which, while itself a trailblazing tool, suffered constant delays and was considered by many a difficult programme to set up. Thus, when Laferriere and team [UnclePunch, Nikki, and metaconstruct] developed Project Slippi, a tool that features rollback netcode rather than delay-based, the game’s online potential took off exponentially. Named after fan-favourite Star Fox character, Slippy Toad, the tool works to minimise latency issues, so if either player experiences any lag, the game predicts what will come next and makes the gameplay near-perfectly smooth. Suddenly Melee could do without lugging around your beloved CRT to your friend’s house, and tournaments could occur online and lag-free.

Being a game from 2001, made for a console with no network features, and no official remakes or avenues to support it online, the only way in which the tournament could conceivably go underway during the Covid-19 pandemic was via Slippi. So, when Nintendo succeeded in cancelling the tournament, the community were there to fight back, barraging the company over Twitter and leading to the creation of the hashtag #FreeMelee. The effort was ultimately unsuccessful but shows in abundance the perseverance of the game’s player base; that while Nintendo refuses to acknowledge Melee’s seemingly endless potential, the community will do whatever it takes to make their game playable to everyone, no matter the distance, and no matter the hardware.

There are other instances where Nintendo have slowed the progression of the scene, such as the battle for Project M, a community-driven mod made to reshape Melee’s lacklustre sequel, Super Smash Bros. Brawl [2008], to resemble the fast-paced, energetic combat of its predecessor. However, in short, Nintendo has not been kind to the Melee community, choosing to perpetuate their exclusive business practises and minimising the game’s accessibility options. And while the company has shown signs of change, with the later sequels, Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U [2014] and the most recent, Super Smash Bros. Ultimate [2018], skewing more towards the competitive scene, Nintendo has yet to fully prove its commitment to the player base.

Over time, Melee has stumbled, fallen and clawed its way to the top thanks to its impassioned community and an extensive meta. Despite Nintendo’s reluctance to support it, and the obstacles that arise when attempting to maintain the playability of what is now a 21-year-old title, Melee’s community remains steadfast and active.

It is a game that just won’t die, and one that, thanks to its loyal and resolute fanbase, will go down in history as the fighting game that was never intended to be one. A casual game that relinquished its design to become one of the greatest competitive fighters ever made. A party game, a fighting game, an accidental masterpiece.

About The Author:

Journalist, gamer, budding screenwriter Simon Jenner explores storytelling through film and media. Connect with me for articles about culture, subcultures and more.