Tokyo Cycling Culture with James Dion from J.D. Cycle Tech

Whether you’ve been working from home or living at the office, you’ve probably never spent so much time inside, surrounded by the same 4 walls and flickery screens.

As a countermeasure, to escape the same mundane routine and scenery, more and more people have re-discovered the serenity and simplicity of the wide-open nature - a more than welcoming sanctuary far-off Zoom call waiting rooms and push notifications.

The newly found or regained motivation to take a break away from our screens, to go outside and explore without a set destination, has been predominantly reflected in a drastic increase in the interest for biking. After all, what better way is there to enjoy a fresh breeze while re-discovering the beauty of your city and area?

While the uptick in demand for trusty two-wheelers has been happening on a global scale, the bike culture in Tokyo has been experiencing a real Renaissance-moment. With young and old folks alike breaking out whatever they had stored in their sheds or Mansion basements, the streets in and around the Japanese capital have been filled with everything from vintage Mamachari’s to the latest and greatest fixed gear rockets.

Image by Kosuke Miyata

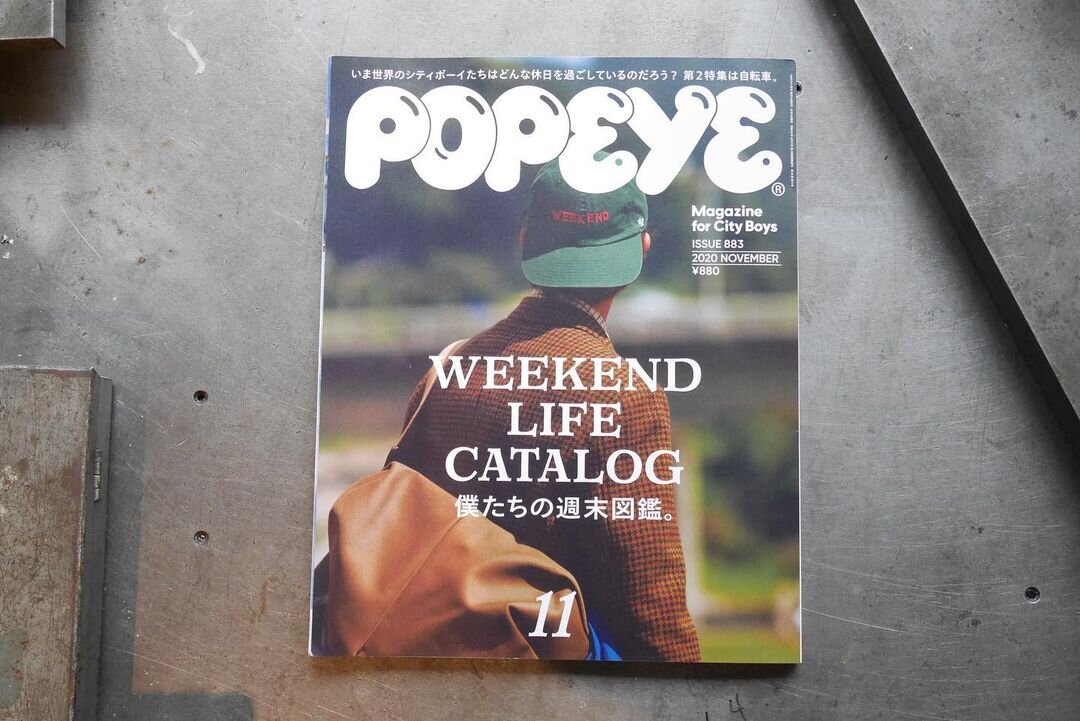

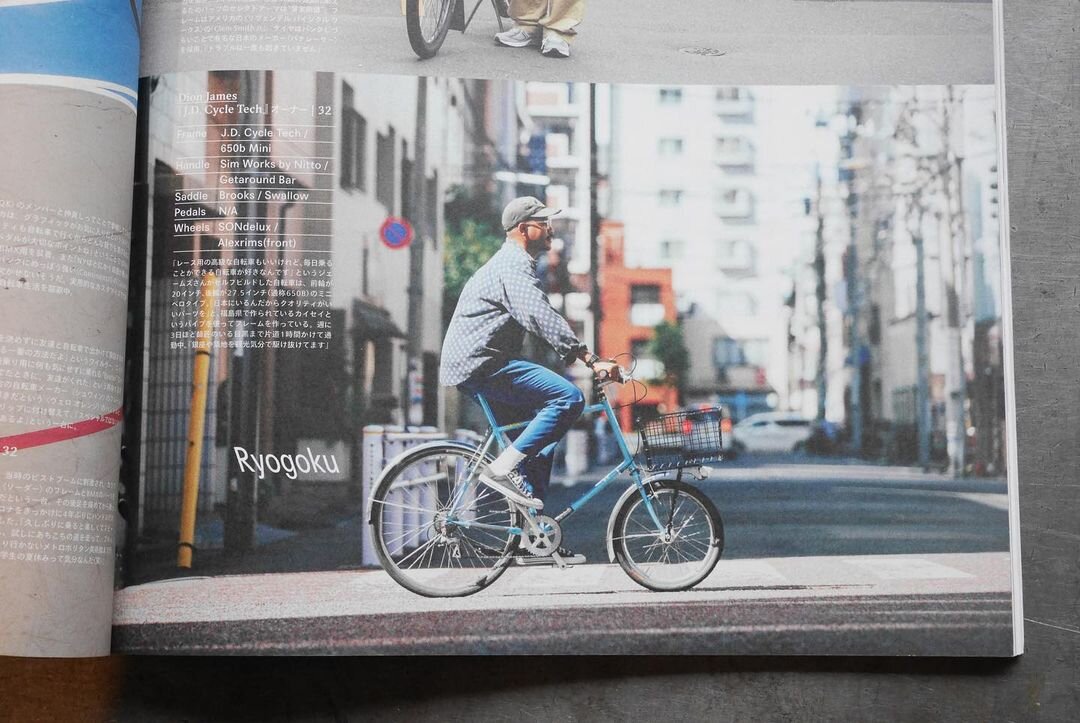

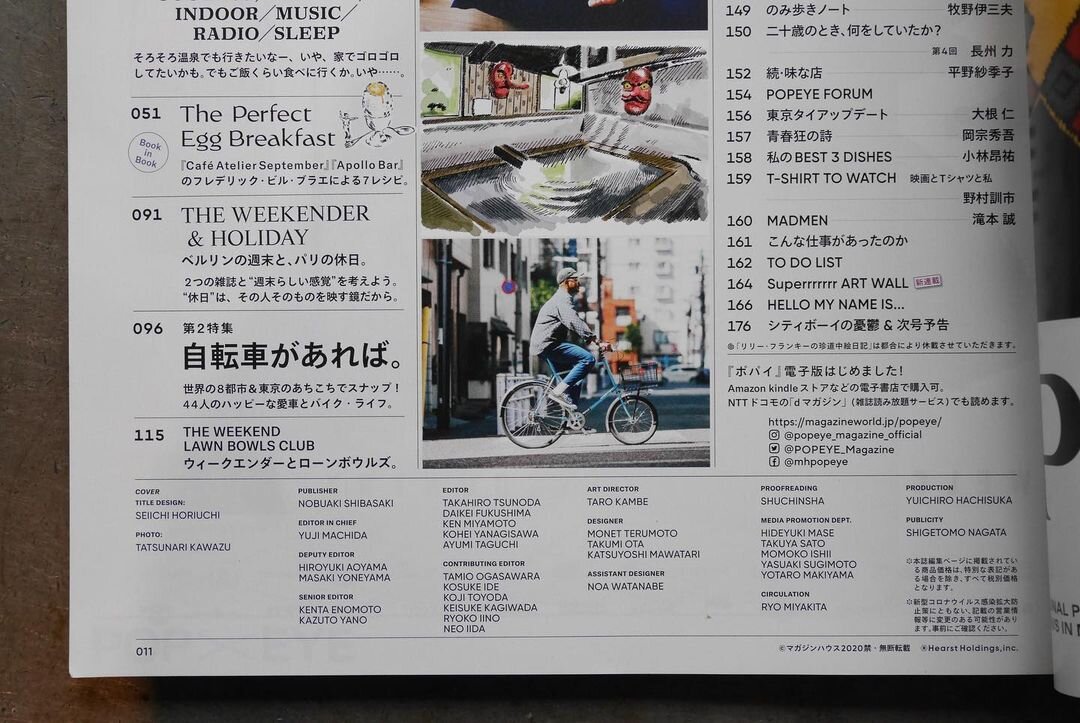

One of the main players and manufacturers of the Tokyo bike scene is James Dion. Since moving from Arizona to Tokyo in 2015, the California-born half-Japanese, half-American cycling enthusiast has paved his own path that ultimately led him to become a frame builder and shop owner. Originally learning his craft from Akio Tanabe of Tsukumo Cycle Sports, the creator of the Kalavinka racing frame, Dion has turned his rare appreciation for bicycles, one that sees frames as individual pieces of art, into his full-time hustle. Operating out of his studio in Sumida, Tokyo, Dion is the founder of J.D. Cycle Tech, a bike shop that employs a fusion of techniques from America’s Henry Ford and Japanese “Wabi-Sabi”. His unique frames have not only won over the hearts of the local cycling community but also landed him features in Popeye, Brutus and even Uniqlo’s LifeWear magazine!

In order to ensure an interview on eye level, we tapped sabukaru’s expert for all things cycling, Arjun Sohal, for the task. Arjun has been working within the cycling industry for a few years now, yet couldn’t be farther from the industry stereotype that goes for daily training rides, shows off Strava screenshots on Instagram or records his maximum power output. Instead, he prefers a calm ride, ideally abroad, where he gets to explore a new city on two wheels at his own pace. And with Tokyo being among his favorite cities to explore on two-wheels, it's an interview match made in heaven!

Having said that, we proudly present sabukaru’s Tokyo cycling extravaganza with James Dion. Enjoy!

Hey Dion, can you please tell us more about yourself and how you got to Japan?

My mother was born in Japan, she got married and moved to the US - she’s a US citizen and totally American - the opposite of Japanese.

I was born in California and moved to Arizona, I’d call it home - I had been there for a very long time. I then moved to Japan and I’ve been here for like 5 years.

You haven’t been in Japan super long then?

I came to Japan during summer break a lot as I visited my grandparents on my mom’s side. We’d come for like 2 months at a time and hang out, me and my older brother. We’re totally close with our grandparents and we spoke English and Japanese at home, so moving here wasn’t too hard. Maybe reading was but speaking was fine. I had friends in college that were Japanese and worked in Japanese owned businesses so there was always something keeping me speaking Japanese.

So what got you into cycling?

I was looking for a bike to commute to and from college - I didn’t have a load of money. I wanted to build it, there were a few styles available - beach cruisers were popular with college students but I didn’t want what everyone else wanted. I found out about track bikes/fixed gears, did some research and saw the tricks and the culture behind it, totally customisable, it looked really fun so I bought a Schwinn road bike, made it fixed and started really getting into it - not just for commuting but for fun, too.

Was this during the Mash SF Era?

The guys doing tricks, MASH, it was a really big cycling culture picking up and I got really into it - it wasn’t something I wanted to do as a career at this point, just something I loved doing as a hobby.

I remember watching MASH SF too, I did what you did to your Schwinn to an old Peugeot frame I got off Ebay. You must have been pushing a light gear to get up those hills?

I really didn’t know much about gears and that sort of stuff back then - thinking back it was a super heavy ratio! It’s funny when I think back, I knew nothing about it but really wanted to learn everything about it. Just taking it all in was so fun at that age.

Yeah for sure, there’s something about cycling and fixed gears which is quite overwhelming as it’s a lifestyle choice if you do it every day, like the way you dress has to be functional if you’re going to be on the bike to and from work.

So how did you get from being a student in Arizona to doing what you do now? Did you study something like metal fabrication?

Nah I did Justice Studies. It's what people do to get into law enforcement, if you’re looking to become a lawyer, something like that, learning about what’s considered good etc… I went to university to get into law enforcement, getting into school I realised I didn’t really like school.

I was just riding my bike all the time, I ended up dropping out of uni and working at a restaurant which was what transitioned my outlook on cycling becoming part of my career. The owner of the restaurant was a former Arizona State student who also dropped out. This Japanese restaurant he owned was quite high quality, a lot of Japanese athletes would visit when they were doing spring training - it was super popular. We got very close. He became like an older brother who was 10 years older. He introduced me to Shokunin culture - dedicating yourself to one thing. He was super artistic, as was I. I loved studying art. Come to think of it, I have no idea why I studied justice studies, probably to make my parents proud.

Regardless, I was really interested in art. When I worked at the restaurant he would say whatever you do can be art, not always putting paint on canvas. The restaurant food is art, made with love - he introduced me to these chefs that truly love what they do. It’s all art. He asked me what it was that I love to do and that got me thinking, all I love to do is ride my bike. That is all I wanted to do. Not necessarily building bikes, I had no idea about that at the time. He just said to find what it is that I enjoyed doing and get after it. I just wanted to live in a big city, NYC, San Francisco, at the time that’s all I thought about - cities and bike riding.

So I thought, to get started I need to work in a bike shop in a big city. I decided I wanted to move my career into cycling around 2014/2015. I ended up seeing a Japanese video of these guys doing the stuff I saw but in Japan. I ended up learning about all these sick track bikes in Japan and an entire culture over there. So then I was like, I speak Japanese and I know the culture so I need to go to Tokyo and see how it goes.

I stayed with my grandad until I could find my own place and everyone in my family was okay with it. I got my visa and moved out here. I’m on a family visa which means if someone lives over here or is from there, I can get a 3 year visa during that time.

I ended up moving here but it was difficult finding a job. However, everyone was so welcoming. I ended up finding a job in a used bike shop and that was basically my foot in the door. But going from the used bike shop to building frames was super strange haha.

How did you get from working in a used bike shop to building the frames?

Some guy came in with a Kalavinka and I was like “dude this is the coolest bike I’ve ever seen, what is it?” He’d come in every so often - he has a load of bikes. We’re still super close, he collects a ton of frames. He told me it was hand built in Meguro, not too far from Tokyo. He went on to say he and his brother in law ordered frames. I was like I have to go see this place and he was so keen to show me. So a week or so later we went to the shop and for the first time I saw the work space. I was thinking to myself, “bikes are hand made, like actual pieces of art - craftsmen who treat it like an absolute art.” This was amazing to me. This is what I want to do. This was the turning point where working at a bike shop turned into a bigger goal, I want to be at an elite level of frame building. I knew right away this is what I wanted to do.

“I was thinking to myself, “bikes are hand made, like actual pieces of art - craftsmen who treat it like an absolute art.”

This was amazing to me. ”

Oh man! This kind of ties back to what the owner of that restaurant back in Arizona was talking about, anything can be an art form, you just need to find the people who take pride in their craft and approach it with that outlook.

I never really looked at work like that at all, this is when it all clicked. Growing up my parents were just like “study hard and work, it will work itself out.”

What was this Kalavinka looking like? Was it an amazing paint job or did it stick out for all the right reasons in comparison to the commuter bikes and second hand used stuff in the shop you were working in?

It was mainly the paint job, Kalavinka is the only frame builder I know that puts Kanji on the frame itself - they would usually build bikes here to look like super European bikes - the Italian look and style is synonymous with cycling culture so the frames here mimicked that. But this totally looked Japanese - unique. I had never seen anything like it before.

How was the workshop? What was the hierarchy there - master frame builder and apprentice?

When we got there it was just the owner Akio Tanabe and the main frame builder. We got to talking and he asked me a lot of questions. Akio tends to do that a lot apparently, a ton of foreigners come to visit and he wants to know about them.

Akio wants to know more about you than to talk about himself which was a really nice surprise. We got chatting and I knew right away that I had to work here, no matter what it takes. Akio is 72 years old and there’s another guy who is 63 and works half the day - he’s done at 3pm. Then there’s one more guy who is 40 years old - he was just about to quit and open his own bike shop in Fukushima. He was about to quit just as I arrived, so I went a week later with a pretty blank resume - just like personal qualities and my education.

Stuff like “I’m diligent, hard working, I won’t ever be late, I work great in a team and also good by myself?”

Yeah exactly that! I had no experience in frame building but I was willing to work hard. Akio obviously was hesitant as he wasn’t looking for anyone and having an apprentice is a headache - letting them in, watching them, teaching them. I just kept going every week - even when I was working at the used bike shop on my days off I’d go hang out at this other bike shop right near Kalavinka, and I’d be like, “hey, what needs doing?” I would be cleaning bikes, building wheels, literally doing anything, for free, on my day off.

One thing I also noticed was that I’d buy this 100Yen coffee from the corner store. I realised they always stopped whenever I turned up to take a break and talk with me - so I’d do this every week and every time they’d be like “oh he’s here again!” They’d always be excited to see me and have a chat about whatever’s going on. We all got super close as a team but 6 months had gone by and no job had been offered to me yet. However, within that period I got my flammable safety gas license which was the only thing I could add to my resume that put me in a good position to work at Kalavinka.

“I would be cleaning bikes, building wheels, literally doing anything, for free, on my day off. ”

I went back to give my updated resume in and just as I arrived there was a customer who arrived the same time as me, he was a really loud guy. As soon as he saw me he was like “oh? you came all the way to Japan from the US to work in cycling, how’s that going?” I was like “I’m learning more about bikes so I can work here!” Akio calls me over to ask if that was true - if I came here because I’m interested in cycling. I obviously told him it was the truth and that it’s all I wanted to do… Akio was like “I’ll think about it.” That was all I wanted to hear. He called me like a week later to start working part time!

So after that, how did you get into frame building? How did you learn all of that part time?

Well when I worked there it wasn’t a step by step process. If you want to learn something, you just have to make it happen. I was taking notes. A lot of notes. It all combined together later. It was a slow process, but Akio found it interesting how keen I was to learn. We would end up building a frame but it was years after me joining.

I’d do loads of filing and because I could speak English, I’d do all the overseas orders, make stickers - pretty much everything and anything. So when I got hired, that guy left and I wanted to know how I could start building frames myself which meant I needed the machinery. A lathe would have been the perfect first piece of machinery, it basically lets you file down metal in a circular tube. This guy knew of someone, so he called around but couldn’t get in touch - turns out this guy he knew was in the hospital! He was old and wouldn't be able to build bikes in the future, so he was trying to sell everything - like the entire workshop! So I went to the hospital and he told me that he wouldn’t be able to continue this passion, it was super sad, but he was excited to see that I was interested in buying and using his equipment as intended.

He gave me the keys to his place, I took a look around and the equipment was exactly what I needed. The stuff took a lot of logistics to move around - I needed a crane to move the stuff from the workshop onto the truck to get it here. The shipping alone cost so much, the machinery was super cheap- he really gave me a great deal. I felt bad but it really worked out well for me - so lucky.

So you’ve now got all of this equipment, working with Kalavinka - how did it come about for you doing your own frames?

I was also still working at the used work bike shop, so I had one day a week to do frame repairs or build frames for friends and family. I’d need specific tools for specific jobs, it’d take a while to get it done but I didn’t want to take orders from strangers as friends knew what my situation was. Not all the tools were mine so I’d have to buy or borrow specific things to get them done then move onto a next project or build.

And fast forward to now, you’ve been covered in Brutus and have a cult following - pretty mad with it being within a couple of years?

One thing that happened with coronavirus is that I got laid off from my job, which then pushed me to work at the store of my own 5 days a week and then work at Kalavinka 2 days a week. Instagram was a huge help - people would hit me up with requests, frame orders, repairs and so on. It really just snowballed!

A friend of a friend in Shibuya is a photographer - she offered to take photos of my workshop, posted it all over socials and someone from Popeye saw them and then contacted me. They were working on a craft/handmade section where they wanted to cover my shop! They are closely associated with Brutus which is how I got into that, the piece should be out later this year actually.

So tell me about your process in building, if I were a customer, how does it go down?

I offer the style of bike first - track, gravel, racing, commuter. If you come to me and say I want this tyre size, this geometry, or this tubing, I can come back to you and say this is what I can do or, come into it on a consultancy basis to see what they’re after, put them on a fit bike to get the sizing correct so it’s perfect for what they want. A bike is really like building with legos, the smallest part can get changed or swapped out for each rider’s needs. So if you know what you want that’s fine. If you have a budget, I work based on that. If you have no idea, I can talk you through the entire process.

What’s interesting is how people think it’s a really expensive thing to do. Some people start off super cheap, then upgrade to a medium level. They might go even higher than that and spend loads on it. I tend to build mid level in terms of price point, which is good for me as I want to build something that people use a lot. Daily if possible. I don’t just want to build something for a ‘best bike’ because a high quality commuting bike is just as important as a high end racing bike. If you take fashion for example, you don’t always need to spend loads of money on an outfit, good quality shoes and denim mixed with thrifted or second hand stuff - all looks good. It’s how I approach frame building - the frame is made really well, and cheap compared to other builders as I can build it quickly. Hopefully people then like to use it and ride it as intended! A lot of times people buy bikes and hang it on the wall like a piece of art- which is fine, but the fun is really in riding it and enjoying it.

What kind of tubing do you use? I know Columbus and Reynolds are two of the biggest suppliers of high grade tubing.

I use Kaisei tubing. A lot of builders use Columbus and Reynolds, they are definitely the brand name and very popular. What I want to do is to build something with Japanese tubing, no one is doing it and the quality of the tubing at that price is the best. The right balance - best bang for your buck. The best tubing from them is just as good as the competitors - stiff, light, thin tubing that is great to work with. Columbus has such a high level of tubing which is great but the cost is so high that I’d rather use a local brand that offer a similar level of quality that I can sell for a lower price, which in turn will let a lot more people buy a handmade bike which is what it’s all about for me. That said, if a customer wants to use a higher quality tube then that option is available for a slightly higher price.

One thing I don't like about cycling culture is how some people flex their more expensive bikes. I really don’t like that. For me I want people to spend money on things that are good quality, used regularly, take a beating, not break and not cost extortionate amounts.

That’s interesting you say that, I wanted to touch on that. How has cycling culture changed since you’ve been within the community? From when you watched MASH SF to where we are now, a huge global growth in cycling even more so recently with Coronavirus.

I think one of the most noticeable trends would be wider tyre sizes. I reckon this is from people being more keen to try off road and gravel riding. I see more people going touring, longer multi day trips too. As it’s a hobby, people tend to spend a lot of money and not necessarily use it. If you spend a lot on it, it will be the best...

Totally, it’s kind of a sporty macho thing to do. Spend all your money on the new pursuit and be the best at it!

Haha yeah totally - such a strange way of looking at things!

I’ve seen a shift in the quality of commuting bikes too, which is good to see as over here in Japan, they have the cheap Mamachari which is like $100, very badly made! People are willing to pay a little more for something better made, more craftsmanship. Possibly a generational change as the younger consumers are willing to pay more for a good quality product that will last longer.

How’s riding in Japan?

I think Tokyo is a great city to ride in. I have a buddy from Seattle who brought his bike here. We’re close friends and every time he comes here we ride from place to place. He’s an artist and likes checking out galleries, so every time we ride he’ll pick out places to stop and check the artwork out. You don’t have to worry about public transportation, just great to ride around and explore.

Anything to add?

The final thing I really want to mention regarding Japanese craftsmanship is the phrase Wabi-sabi; They don’t really talk about it, it’s more of a feeling. That’s one thing I learned whilst working at Kalavinka. Keep things simple but have enough going on so that it’s interesting. Find the balance between busy and boring, mundane and chaotic. That always changed throughout time - for example in the 80’s things were super busy, over the top and had flamboyant designs, whereas during the early 2000’s things were more simple and paired back. That was something my mentor Akio taught me whilst being at Kalavinka. His mentor told him that you have to study design. When I first got there I didn’t know much about it. I saw the workshop and thought to myself this is what I wanted to do, but a lot of frame builders make their own lugs [bits that connect the tubes together].

Kalavinka make their own lugs. The frames I make are basically a replica of a Kalavinka. They don’t do gravel bikes but if they did, it’d be similar to what I create. Elite frame builders make their own lugs, Cinelli makes them and they are world renowned. Nagasawa over here are huge - like 10 time racing champions, they make their own.

My dream is to build my own, but for now I’m just focusing on design.