Visual architects of Tokyo style: Stylists on silhouettes, resistance and self

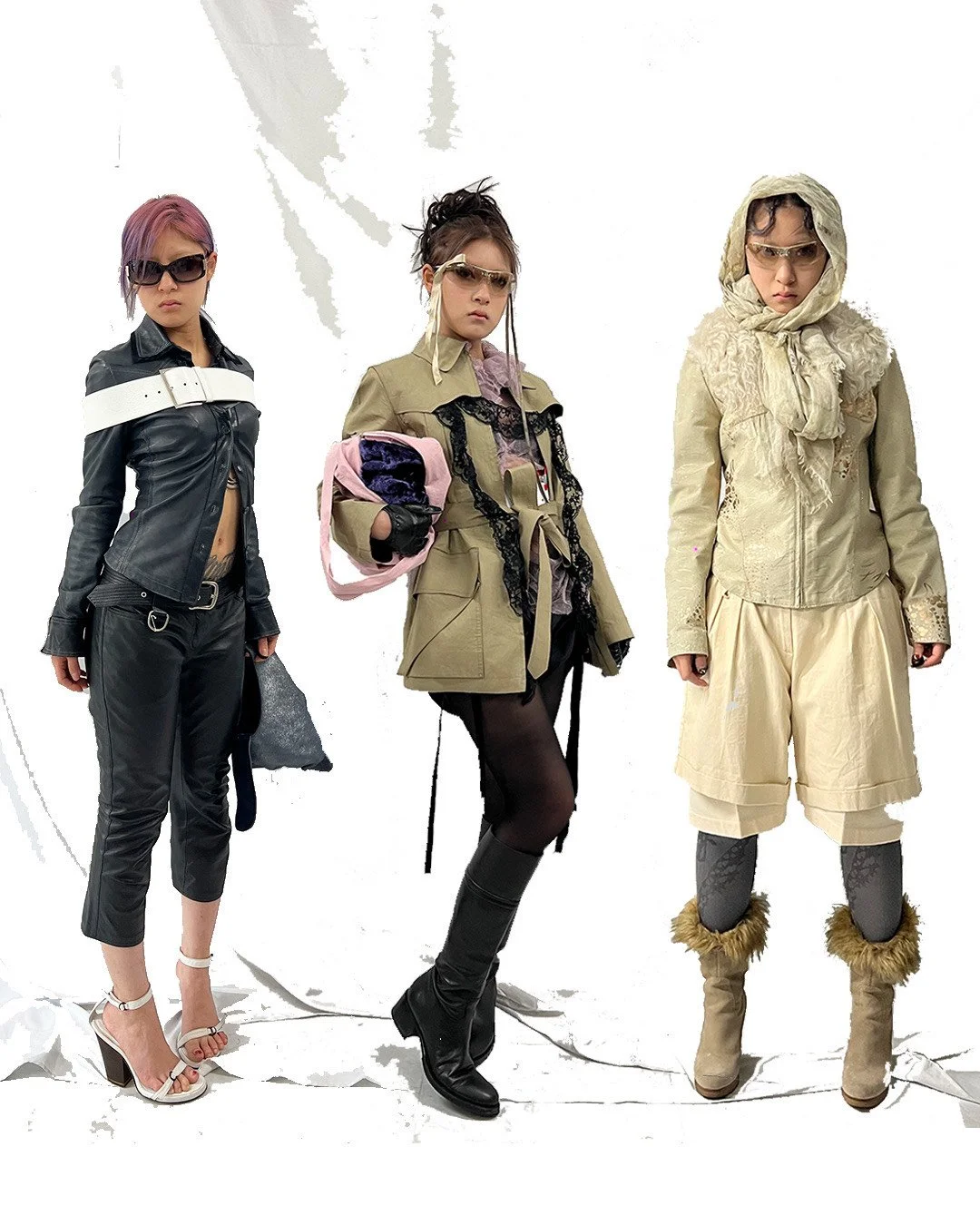

If you are interested in fashion in any capacity, your eyes have been on Tokyo at some point. In the largest populated city in the world, it’s not surprising to want to understand how people craft their outfits. In Tokyo, people treat clothing as language. Whether you flip through old copies of Popeye, FRUiTS, CUTiE, Street, or Soen (to name a few), or watch the many videos online today asking people on the streets of Tokyo what they’re wearing, the language begins to show itself off. You begin to wonder then, what does it mean to style garments, and how? sabukaru spoke with three undoubtedly elevated Tokyo-based stylists—Eve Lantana [@eve_lantana], Ki Ukei [@kiukei_], and Dominika Szmid [@domsyn]—about their styling process and how they use the human figure as a framework. To them, garments become tools for self-construction, resistance, and visual storytelling, ultimately redefining what a body can communicate when styled with intent. What emerged was a deeper conversation about silhouettes, philosophy, and the art of styling in Tokyo’s ever-evolving fashion scenes. Read the full interview, link in bio.

First, could you introduce yourself to sabukaru?

Eve Lantana: My name is Eve Lantana, and I work as an art director at a store called "KAKKO" in Tokyo. In parallel, I also occasionally work as a stylist. It’s been about a year since I began working in a full-fledged capacity. However, my exploration of form through the human figure and stylistic thinking has continued since my student days studying architecture. In that sense, styling for me is not merely about clothing manipulation—it is a medium of expression.

Ki Ukei: Hello sabukaru, it’s Ki Ukei here. People call me Kiu. I’m an independent fashion stylist working between Tokyo and Shanghai. My practice spans visual direction, brand styling, and concept-driven editorial work. I’m drawn to building visual languages and disrupting conventional dressing systems. My styling often lives in the tension between pop culture and futurism.

Dominika Szmid: My name is Dominika, and I’m a stylist and consultant living and working in Tokyo. I’m originally from Poland, and this year marks my 10th year in Japan. When I first moved here, I didn’t plan on styling or even staying this long. It started more as a fun project with photographer friends visiting Japan. At the time, I was studying at Bunka Fashion College, which gave me access to all the crazy clothing made by students. After doing a few non-fashion-related jobs, I enrolled at Bunka with an interest in design (like most people), but I found working on set more satisfying, at least for now!

How do you approach building a wardrobe for styling?

Eve Lantana: First, I begin by carefully capturing the “vibes” of the project. Then, I proceed with selecting items and shaping the overall form simultaneously. Finally, while envisioning the complete image including body poses and negative space, I add elements such as accessories and details to complement the compositional balance and refine the look.

Additionally, at each stage of styling, I sometimes create abstract schemata through drawings that explore textures, silhouettes, and their relationship to the body. By frequently shifting perspectives and working with my hands in two dimensions to construct shapes, I can sometimes evoke a form that is unconventional and, in a sense, possesses an eccentric quality. I’m not particularly attached to specific brands, but I often use garments that carry the weight of time—vintage or antique pieces. Patina from aging, such as fading and distressing, is a visually and conceptually important component in my styling. While I often work with basic silhouettes, I aim to discover new expressions by altering or breaking down the conventional ways they’re worn.

Ki Ukei: I treat my wardrobe more like a toolbox than a closet. I focus on materials, structure, and how many times a piece can be reinterpreted. I’m not interested in collecting “full looks”—I’m interested in modularity and transformation.

Dominika Szmid: I think I am quite analytic in the process; I like to do my research on the type of character/situation we want to create. I also take inspiration from beyond fashion, often looking to art, film, anime, and everyday life for interesting colors or ideas. While I have a core set of fashion inspirations, I find that each new project pushes me to update my "visual database." Every time are always new factors to consider. When collaborating with a client like a brand or an artist, I pay attention to their "world", think about how I can add to or reinterpret it, and show what I think is the most interesting about them.

When was styling the most meaningful to you?

Eve Lantana: For me, styling is just one of several means of output. In that sense, I don't rank it in any particular way compared to other fields such as sculpture or spatial design.

Since my student days, I have consistently placed importance on a cross-disciplinary approach, and rather than there being a moment when styling became particularly "meaningful," I feel that it has always functioned in parallel with other means of expression.

Ki Ukei: One of the most meaningful moments for me was directing and styling the editorial cover shoot for TUNICA Magazine. It was the first time I led the creative direction for a cover project, and I was given an exceptional level of freedom in styling. The entire team shared a strong creative mindset, and I’m truly grateful for that.

Dominika Szmid: When I can use it to support the work of people I root for and respect.

Talk about your style philosophy.

Eve Lantana: To draw out maximum effect through minimal intervention, and to focus on composition.

Ki Ukei: To me, styling is a form of translation—and disruption. It’s not meant to provide answers, but to provoke questions. A strong look should linger in the mind, not just look good at a glance.

Dominika Szmid: Style and clothes can help to communicate to the world what kind of person you are. But if they don't fit your lifestyle, they will become just a costume.

Describe your personal style in three words.

Eve Lantana: Anti-Architecture, Deconstruction and Composition.

Ki Ukei: Narrative. Subversive. Powerful.

Dominika Szmid: Minimalist, Monochrome, Punk-Edge

Has there been a collection that left an impression on you upon watching a particular fashion show?

Eve Lantana: It’s something that keeps changing, but one that left a strong impression on me was Hussein Chalayan’s collection from 2000. His conceptual approach—untethered from conventions or specific domains—and the way he traverses function and symbolism resonate deeply with me.

Ki Ukei: There have been many shows that left a strong impression on me—it’s hard to pick just one. But recently, Margiela Fall/Winter 2024 stood out. I’ve always admired John Galliano. His meticulous control over every element—the narrative, music, lighting, and the emotional expression of the models—is simply unmatched. The level of cohesion and emotional impact in that show was deeply moving and unforgettable.

Dominika Szmid: Watched on YouTube, but Mugler Insect Woman Haute Couture collection from 1997. I love all the drama and sexiness!

What are some references for your styling?

Eve Lantana: "Anti-Architecture." In Japan, this concept was notably advocated by Arata Isozaki. It doesn’t mean opposing architecture outright, but rather radically re-questioning the thought systems and authority structures that underpin it. I interpret this not just as a theory limited to architecture, but as a universal methodology that applies across design processes and even beyond.

Ki Ukei: To me, styling is a visual medium through which I express my art. Inspiration can come from anywhere—artworks, architecture, music, even current political and social events. All of these elements inform my creative process and find their way into how I construct a look.

Dominika Szmid: Definitely where I grew up and what people around me were wearing influenced me. My region in Poland had a strong punk and rock music scene, and that aesthetic has stayed with me. Later, as a teenager with internet access, I became obsessed with anime, Visual Kei, and Japanese street style. I’d say those are still some of my core references today. Just last month, I did a personal project inspired by 哀しみのベラドンナ (Belladonna of Saddness), one of my top favorite animation movies.

What do you think about bad taste? Does it exist in design and fashion spaces?

Eve Lantana: My aesthetic stance is that I am resistant to things that incorporate too many elements. It's not just a matter of taste, but also a concern that information overload can obscure the essence of things. As for the question of whether "bad taste" exists, I don't think it's an absolute standard, but a relative concept that changes greatly depending on the context, intention, or sensitivity of the recipient. However, if there are too many elements without any intention, it may end up being considered "bad taste."

Ki Ukei: “Bad taste” is just a socially coded discomfort. In visual work, it has a function—it can create friction, disrupt hierarchy, trigger unease. And I’m interested in all of that. For me, it’s not a mistake—it’s a tool.

Dominika Szmid: Bad taste is just copying something without your own input. Unfortunately, it does exist in both of these spaces. But if you’re following your own ideas, I don’t think it can really be called bad taste—there will always be someone who connects with it.

Does the direction of fashion and design motivate you in your work?

Eve Lantana: I mainly create work that reinterprets the movements and methodologies of the early 20th century in a modern way, so I am not directly influenced by recent fashion trends. However, I am strongly attracted to unique expressions regardless of genre, and I check the activities of various artists every day. In that sense, I may be taking a stance that draws inspiration from the current atmosphere and individual artists' personalities while basing my work on 20th-century thinking.

Ki Ukei: Yes—not in a trend-following way, but in a systemic way. AI-generated images, digital bodies, visual fatigue in hyper-consumption—all of these push me to ask: Why do we wear what we wear? What are we actually communicating?

Dominika Szmid: I do feel excited about the technological innovations in fashion, like new animal-free leathers or recycled fabrics. But, when it comes to things like seasonal trends, picking up one or two can be fun, but overall, I prefer to look to the places beyond for motivation.