Themes Of Adolescence in Spirited Away and Your Name

Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away was the highest-grossing anime film of all time from the year of its release in 2001 until 2016 when it was overtaken by Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name.

While Spirited Away succeeded in reclaiming the title that same year, Matthew John Paul Tan claims that, ‘with Miyazaki ostensibly going into retirement, Shinkai is now being billed as one of the front-runners for the directors most likely to fill the void in anime that Miyazaki left behind.

As with many anime films from the two decades in which they were released, a common theme running through both is adolescence and growing up.

While critics assert that Shinkai explores ‘such parameters as adolescent love, adult melancholia and the disappearance of adolescence, Miyazaki himself states that Spirited Away is dedicated to those who ‘were once ten years old, and those who are going to be ten years old.’

Sabukaru will compare Your Name and Spirited Away, the most successful works of each of these prolific directors within the genre of Japanese animated film to explore whether their portrayal of adolescence has changed significantly over the course of a decade and a half, or if similar themes and imagery continue to be used.

In both Spirited Away and Your Name, losing or forgetting names is a metaphor for the loss of identity, and there is an importance placed upon the necessity to remember names. In Spirited Away, Chihiro must sign her name away to Yubaba, the owner of the bathhouse, in order to earn a job there. Instead, she is left with the name Sen, which she must use until she leaves the spirit world.

The name Chihiro, written as 荻野千尋, ‘signifies “very deep” or “unfathomable,” as in the phrase chihiro no tani (a deep valley).

Over the course of the film, she begins to forget her original name, suggesting that she is beginning to lose touch with the human world, and implicitly, her identity, as a name is so deeply entrenched in who one is. Lucken explains that linguistically, the name Chihiro, written as 荻野千尋, ‘signifies “very deep” or “unfathomable”, as in the phrase Chihiro no Tani (a deep valley). However, Sen, written with the simple character 千, is generally considered to be a boy’s name. Furthermore, ‘in Japanese, the word “line” is also pronounced sen’. Therefore, for Chihiro, having her name changed to Sen is symbolic of a loss of depth and complexity, leaving her with a name that represents nondescript shallowness and ambiguity even in gender. As a result, she begins to lose touch with her original identity in the human world.

The title of Your Name immediately establishes the significance of names and their link to identity within the film. When protagonists Mitsuha and Taki swap bodies, they are temporarily de-named and must infiltrate each other’s name and identity, playing along with the rules of the other’s life. However, the longer they are apart from each other, the more the memories of each other fade away until they can no longer recall each other’s names, and as a result, identities.

It can be inferred that in both Your Name and Spirited Away, the recalling of a name brings about power and liberation.

At the climax of Spirited Away, Chihiro remembers Haku’s real name, Kohaku, allowing him to connect with his true self, the spirit of the Kohaku River. This allows him to free himself from the contract tying him to the bathhouse and Yubaba’s apprenticeship.

In Your Name, Mitsuha and Taki are able to find a true, real-life connection after asking for each other’s names when they finally find each other during the same timeline at the end of the film. Reider explains how this element of Spirited Away was inspired by Le Guin’s Earthsea Quartet: ‘When a girl in the second book remembers her true name, her memory as a human gradually comes back and she fights against the dark forces’. While this concept directly influences Spirited Away, the same theme can be applied to Your Name, reinforcing the significance of renaming as a form of emancipation from the confines of a lost identity in contemporary anime.

Spirited Away’s Japanese title, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, translates to ‘Sen and Chihiro’s Spiriting Away’. The fact that the original title includes both names, recognising Sen and Chihiro as different identities, suggests that the film depicts a transition from one state of being to another. The shifting of the self from Chihiro to Sen and then back to Chihiro once more is perhaps a metaphor for a shifting identity in adolescence, a place of unsureness, of change, and even of losing oneself along the way in order to come out of it the other side with a greater understanding of who one is. The same idea can be applied to Your Name; Mitsuha and Taki’s takeover of one another’s names, forgetting each other’s names and reconnecting and remembering as they enter adulthood represents the constant change and upheaval of the self as one grows up until one finally is able to gain stability as an adult.

Additionally, both anime films feature a rich history of folklore and spirituality, drawing on the traditions and rituals of ancient Japanese culture.

The vast array of mystical spirit characters in the bathhouse takes inspiration from the traditional Shinto religion of Japan and its eight million gods or kami, bringing together the present day and the spiritual beliefs of the past. The Japanese title includes the word ‘kamikakushi’, meaning ‘hidden by kami’ which emphasises the influence of Japanese folk belief on the film. Furthermore, Reider alleges that ‘[in] the past, when children or women suddenly disappeared and could not be found for a long time, it was presumed “they had met kamikakushi”. The fact that Chihiro essentially meets kamikakushi by entering the bathhouse reinforces the heavy influence of Japanese folk belief on not only the characters but also the narrative itself.

In Your Name, Mitsuha’s traditional upbringing in the countryside connects her closely to the Shinto religion.

Early on in the film, she and her sister perform the ritual in which they ‘[leave] an offering of sacred kuchikamizake, a form of fermented sake that was part of the traditional rites performed by Mitsuha’s family as hereditary custodians of the local shrine’, as described by Alisdair Swale. Here, they take on the role of Miko, who are seen as ‘mediums’ (Kentarō) between the human and spirit world. The fact that Mitsuha undertakes this ritualistic role allows her to transcend the boundaries between the physical and the spiritual. The unclear space between these two realms that she is able to occupy is reminiscent of the ambiguous space adolescence takes up between the boundaries of childhood and adulthood. This suggests that the process of growing up may allow one to grow closer to spirituality, as seen by the relationship with the spirit world that the protagonists of both films experience in their adolescence.

Miyazaki believes that [surrounded] by high technology and its flimsy devices, children are more and more losing their roots. We must inform them of the richness of our traditions. This emphasises the significance of Japanese folklore’s feature in anime films as a means to enrich the children its narratives appeal to within the culture they otherwise may not be as exposed to due to the rise of a new, highly technological world. Folklore transcends the margins of the here and now, blending the past and present. Much like the boundaries between childhood and adulthood, there is a mystery and ambiguity surrounding folklore.

During the process of growing up and changing between an old and new self, the new self, while an almost entirely new person, still holds memories from the past, much like how folklore brings lingering memories and traditions of the past into the present day.

Liminality and liminal spaces are especially significant motifs in Spirited Away and Your Name. Megumi Yama argues: ‘The very style of anime is particularly well aligned with the Japanese cultural tendency towards ambiguity’. Japanese animated cinema is therefore well-suited to the liminality present in both films, implying that it is a common trend amongst films of this genre. Chihiro is often depicted in liminal spaces:

holding her breath as Haku guides her across the bridge;

crawling fearfully down the rickety stairs along the side of the bathhouse;

hiding behind the Radish Spirit in the lift up to Yubaba’s office. The frequency at which these liminal spaces appear is no coincidence; They are a subliminal metaphor for adolescence, the liminal space Chihiro is experiencing internally. Reider claims that ‘conventionally, in the world of Japanese folklore, bridges, tunnels and crossroads are often considered to be a demarcation point between this world and another’. From this, it can be inferred that, while these reoccurring places represent a transition between the human and spirit realms, this alludes even further to the transition between childhood and adulthood which follows Chihiro throughout the narrative as she grows and matures within the bathhouse as a result of the spirits she interacts with and learns lessons from.

Even the bathhouse itself is liminal, which is implied by Miyazaki here: ‘Japanese gods go there to rest for a few days, then return home saying they wished they could stay for a little while longer.’ It can be inferred from this that it also serves as a place for Chihiro to pass through, returning home afterwards with a new and developed sense of self.

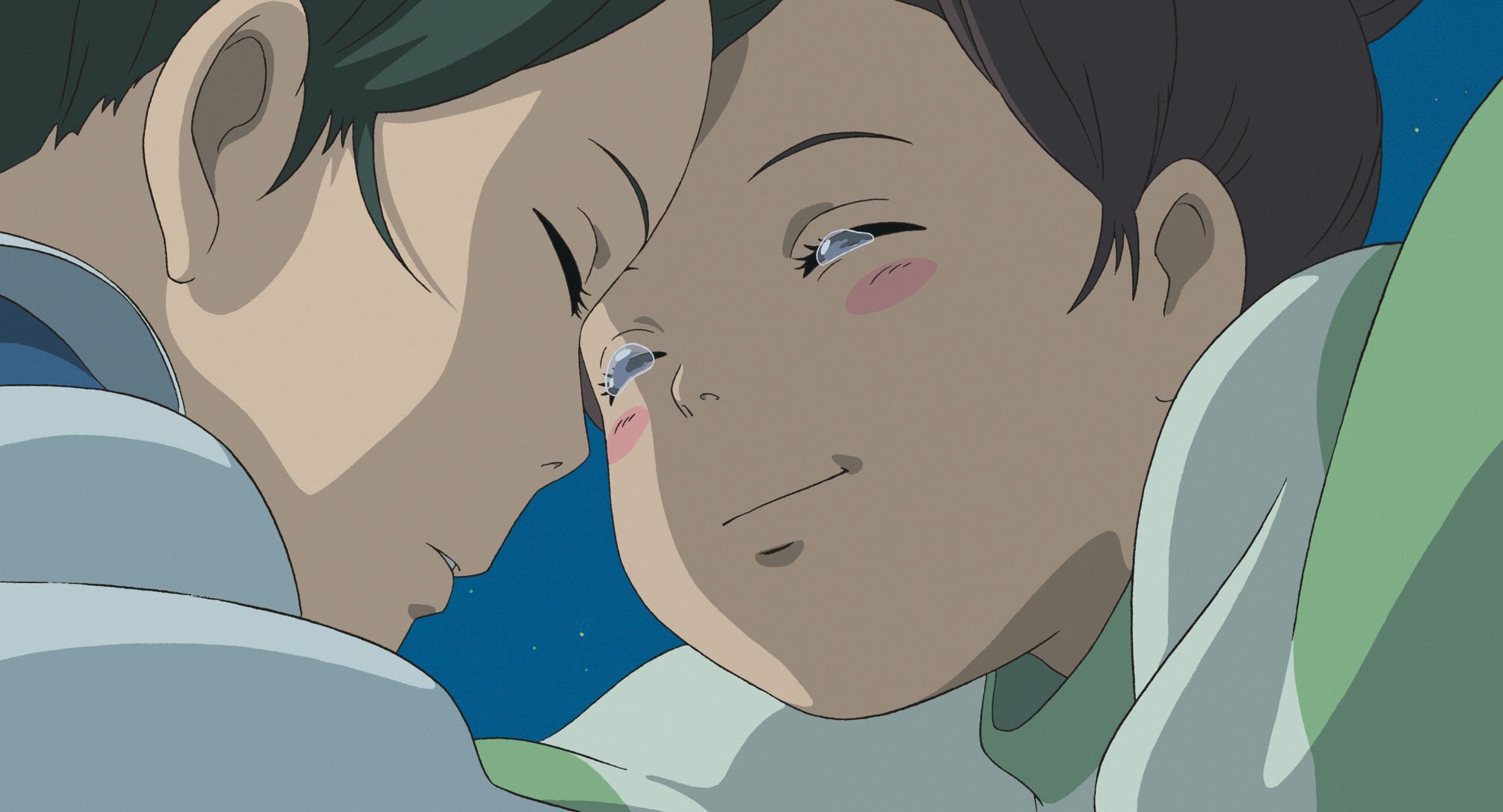

Similarly, the two protagonists of Your Name are often depicted in liminal spaces, repeatedly shown to be travelling from place to place, most often being from home to school.

This makes the fact that they finally catch sight of each other in the same timelines on the train, and the fact that the ending scene in which they finally stop to speak to each other takes place on stairs, particularly noteworthy. These moments signify the conclusion to their adolescence as they now enter adulthood with a more stable idea of who they themselves, and each other, are. The liminal spaces in which these events occur serve as a reminder of the transitional period they have gone through together and are just beginning to come out the other side of.

Moreover, Your Name features the motif of twilight, which can be described as a liminal time in the day where it is neither day nor night. In the first classroom scene of the film, the teacher describes twilight as ‘When the world blurs and one might encounter something not human.’

Further, Taki and Mitsuha are able to connect and speak to each other for the first time at the viewpoint during twilight. Of this phenomenon, Swale says: ‘[The] notion of tasokare 誰そ彼, or twilight […] etymologically conjures up the question “who are you?” or “who is there?” Tasokare is quintessentially liminal space […] and in Shinkai’s adaption, it constitutes a zone that facilitates movement across the past, present and future’. This motif heavily alludes to the blurring of the childhood and adult worlds during adolescence and a state of change between one stage and another.

When Taki drinks the kuchikamizake made from Mitsuha’s saliva, he is able to invoke a liminal realm into existence, rather than previous instances in which they have been subject to liminality occurring around them involuntarily. By consuming her essence, he is able to transcend, and enters a liminal space between worlds where he can connect with Mitsuha and learn more about her past.

Chihiro, on the other hand, must eat the food of the spirit world in order to not fade away, so she can maintain her presence within this liminal bathhouse. In Spirited Away, Yama claims that ‘appetite becomes a significant theme and a link between the act of ingesting food with a sense of integration and a desire for unity’. This could also be said for Your Name; In both films, the act of consumption allows for an access to a higher realm for the protagonists which enables them to connect with others and progress in their journey towards adulthood.

The concept of soul connection is important when exploring the relationship between characters in both films. It is established by Swale that Shinkai’s ‘earlier films are emphatically in the sekai-kei (世界系) genre that focuses on the emotional predicament of contemporary young people, who feel alienated and seek a significant other to share their predicament with’. Before the body-switching begins in Your Name, both protagonists long for what the other has. Mitsuha proclaims: ‘I hate this life! Please make me a handsome Tokyo boy in my next life!’ By switching bodies, the two are able to ‘share their predicament’ of growing up, alongside the more pressing predicament of saving Mitsuha’s town from destruction by a meteor shower. The bond between the protagonists is different from a regular relationship, as they grow close to each other in the process of essentially becoming one another.

Their relationship even extends beyond the boundaries of time, as they are able to defeat all odds and work together to save each other despite existing in different timelines. Even after losing all communication with one another, they are still able to reconnect at the end of the film in adulthood. When describing their relationship, Swale says: ‘There is a certain poetry in the way that Shinkai has taken the familiar notion of the deepest kinds of love that somehow feel predestined, and seem capable of enduring beyond this life’.

This idea is not exclusive to Your Name, and seems especially reminiscent of Chihiro and Haku’s connection, which enables him to retain his original identity as the Kohaku River. The fact that they subconsciously knew each other long in the past conjures up this idea of ‘predestined’ love that goes beyond the present day and dates back to far before the events portrayed in the film even take place, suggesting that they were ‘meant to be’.

Symbolic red hair ties in both films also link to ideas of soul connection.

Mitsuha wears a red hair tie to school every day which is created using the traditional method of braiding and knotting thread depicted several times throughout the film. On their walk to the shrine, Mituha’s grandmother explains musubi: ‘Tying thread is musubi. Connecting people is musubi.’ This explicitly creates a link of Japanese tradition between her hair tie and symbolic relationships between people. Taki accidentally takes Mitsuha’s hair tie from her when she goes to visit him before he is even aware that she exists. Regardless, he continues to wear it until they meet again. In this way, the hair tie is the physical tether which connects the two, transcending the barrier of differing timelines between them. Similarly, Zeniba weaves a red hair tie for Chihiro with the help of No Face, mouse Boh and Yubaba’s bird, which she is able to bring home with her as a reminder of her experience. Reider argues that ‘Chihiro’s hair band […] – its glittering underscores the hint – provides evidence of the objective existence of the “other world.” (p. 7) Much like the hair tie in Your Name, Chihiro’s hair tie exists in both worlds, serving as a connection between one and the other.

The close-up on Zeniba and Chihiro’s hands as she hands over the hair tie is interrupted by a diagonal line cutting the frame in half in the background. While Zeniba’s hands fit into one half of the diagonal and Chihiro’s into the other, the hair tie crosses over the line into both halves of the frame, strongly implying that the hair tie crosses over between the spirit and human worlds. Additionally, the red thread of fate is a key feature of East Asian mythology, theorising that each end of a red thread is tied on the fingers of two people who are destined to be together. This indicates that while this red thread of fate is tied to the fingers of Mitsuha and Taki, for Chihiro, the other end of her thread may be tied to both Haku, but also the spirit world as a whole. For the protagonists from both films, this fateful love and soul connection is the thing that allowed them to grow and develop, with someone by their side to help them through adolescence.

Both Miyazaki and Shinkai use nostalgia to evoke a longing for the lost youth in the viewer. One of the most recognisable ways in which Miyazaki creates feelings of nostalgia is through moments of ‘ma.’ (Renée) Roughly translating to ‘emptiness’ in Japanese, these moments characterise Miyazaki films.

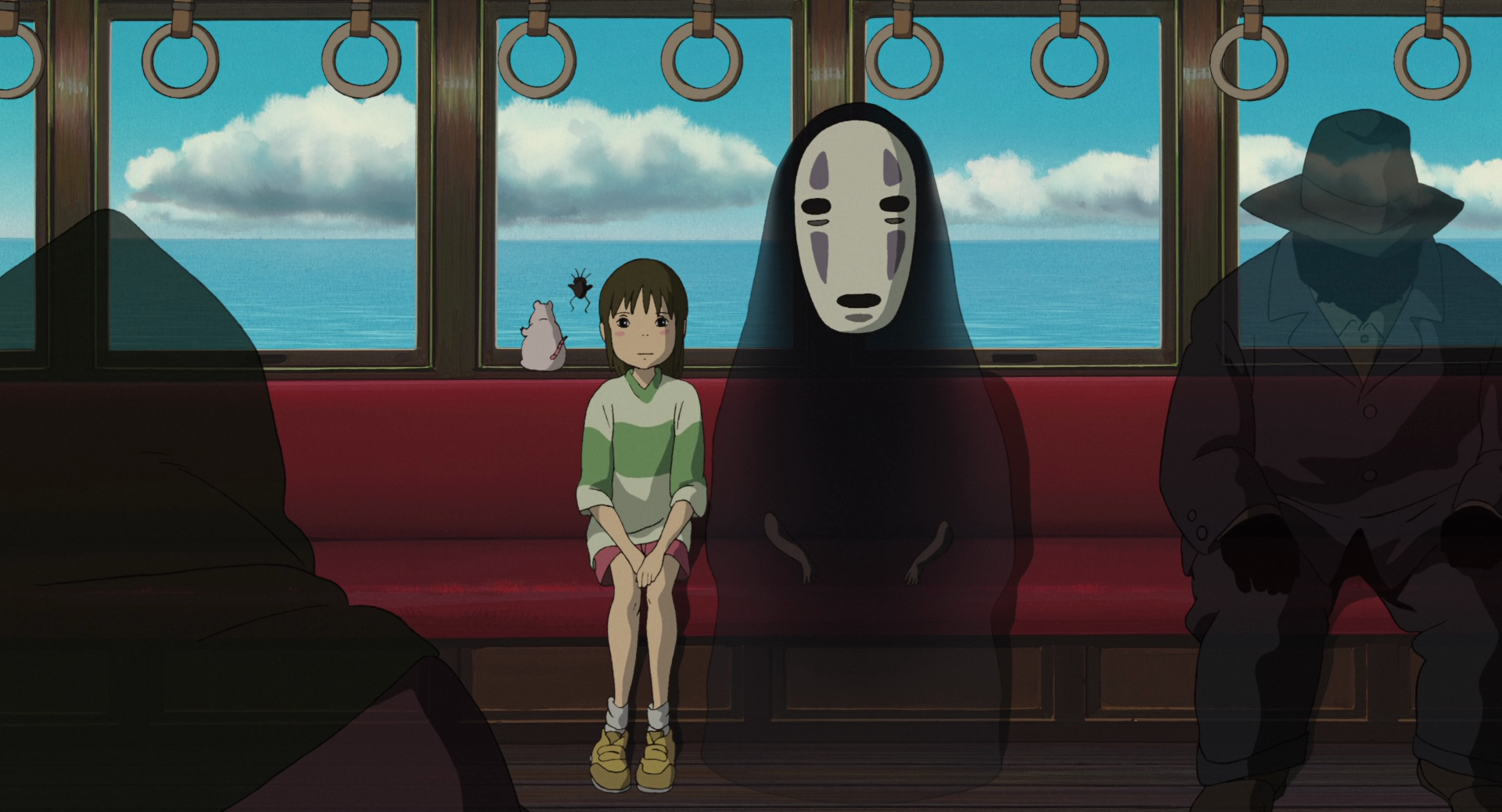

The train scene in Spirited Away is one of the most renowned examples of this technique, in which a whole four minutes of screen time is dedicated to wordless animation of Chihiro and her new companions watching landscapes drifting past, accompanied by Joe Hisaishi’s evocative and melancholy soundtrack. Of such scenes, Miyazaki says: ‘The people who make [American cinema] are scared of silence [….] What really matters is the underlying emotions – that you never let go of those.’ (Renée) Periods of ma are especially poignant as they are almost overpoweringly nostalgic, allowing the viewer a pause from the chaos of the action to breathe and reflect. This experience is reminiscent of the feelings of nostalgia felt after finding opportunities in the relative quietness of adulthood to reflect upon the ever-changing chaos of the self in adolescence.

Nostalgia is also evoked in adult viewers of Your Name through a feeling of loss and longing for the past. Critics reinforce this sense of loss: ‘In the corpus of Shinkai’s anime, love adverts to the loss of innocence, and it is always the adult gaze towards children and adolescence that provokes this feeling of loss, while simultaneously attempting to preserve it.’ (Anon.) Here, this sense of loss when watching Your Name pertains to the uncanny, or in Freudian terms, the ‘unheimlich’, described by Summers as ‘the pain of homecoming’. In the unheimlich lies the idea of simultaneous familiarity and unfamiliarity, where the youth one once knew has now passed. While these emotions are evoked in the viewer throughout the film as we follow two teenage protagonists through their youth, they are felt particularly strongly when Taki discovers that Mitsuha’s town, Itomori, has already been destroyed.

As he researches Itomori and travels back to the shrine, familiar images appear of places he once visited in the body of Mitsuha. Except now, they have changed. Three years have progressed, Itomori no longer exists, and his memories of the place have begun to fade. These same places are so familiar, yet completely different. They are unheimlich, creating nostalgia for what once was. In this way, Your Name and Spirited Away’s portrayal of adolescence is recognisable and comforting to those watching who are currently experiencing it themselves, meanwhile, for those who have now entered adulthood, it feels familiar yet far away, and therefore nostalgic.

The films Spirited Away and Your Name of Hayao Miyazaki and Makoto Shinkai respectively demonstrate that contemporary Japanese animated film has not changed much in regard to how it represents growing up and those who have either gone through it or are currently going through it. While the experience of growing up in 2001 is very different to growing up in 2016, mostly as a result of the rapid technological developments in communication and entertainment that have occurred in the time between these films were released, both still accurately capture the familiar feelings of confusion, unsureness, displacement and growth that come with adolescence. And while modern cultures constantly change and shift, both films possess an element of timelessness due to the influence of ancient folklore and spirituality. Both films are filled with a liminal metaphor which creates an overall tone of ambiguity, faithfully reflecting the indistinct period between childhood and adulthood that is relatable to all who encounter it.

About the Author

Delilah Calodoucas is a film and literature student from London, based in Bristol. With a passion for Japanese art, music and fashion, she is on a constant search to discover niche subcultures to write about. She is a lifetime fan of Studio Ghibli and psychological thriller anime cult classics, with aspirations to become a Gothic Lolita.