The Space Between Two Worlds: How Music Shaped Cowboy Bebop

Shinichiro Watanabe revolutionized animation with one idea, the gap between music and anime as the centre of the creative process.

Well known for directing Cowboy Bebop [1998], Samurai Champloo [2005], and Space Dandy [2011], Shinichiro Watanabe has demonstrated an influence upon anime culture only comparable to the Mamoru Oshii, Satoshi Kon, and Katsuhiro Otomo.

With more than 20 years of activity, the director has proven a rare consistency in his work – a Midas’ touch you could say – building a name based upon animation quality, touching storytelling, iconic characters and, and for the matter of this text, legendary soundtracks.

Further than ‘just’ songs, music shapes Watanabe. Experimenting in the gap between sounds and images, the director - and collaborators - have created anime that feels like a Jazz session, told a story like sampling in Hip-Hop and, conceptualized a whole series as a Music Festival.

The following piece is enrolled in a three-part series to talk about the director’s work. Going through Cowboy Bebop and Samurai Champloo, we’ll discuss creative processes and how translating ideas from other fields let us rethink our practice.

This first part focuses on the acclaimed Cowboy Bebop and Jazz music. Let’s jam.

Days Before Cowboy Bebop.

Shinichiro Watanabe never went to an academy to learn about cinematography. He absorbed everything about filmmaking himself. Through books, Watanabe had access to movie production, film techniques and all technology involved.

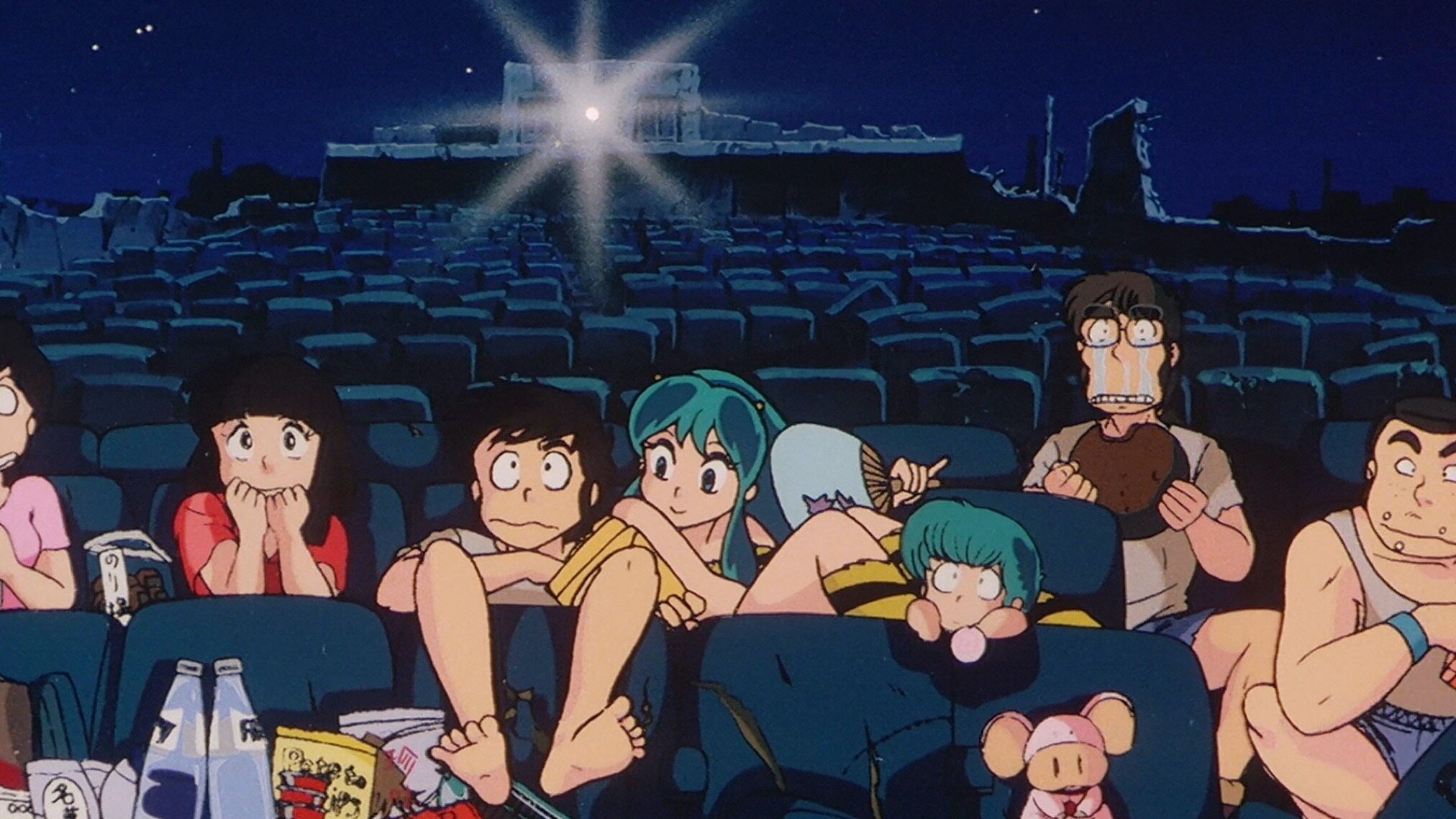

His relationship with animation started in 1984. In this year, three influential Japanese anime movies premiered; ‘Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind’, ‘Urusei Yatsura: Beautiful Dreamer’, and ‘Macross: Do You Remember Love?’. These productions proved a statement about national cinema; the possibilities and creative freedom of animation were ahead of photography-based cinema.

Anticipating these possibilities, Watanabe moved towards animation. He once stated: "At the time, all those films exceeded any of the qualities of the live-action films being made in Japan. I always wanted to make films, so at the time I thought it was better to go into anime than live-action for film-making."

Consequentially with this decision, our protagonist enters Nippon Sunrise – an animation studio – as a producer. Watanabe’s vision was to ‘actively sought to animate original works, rather than adaptations of pre-existing manga series.’ Sunrise was the right place to start.

His first big moment came in 1994. Asked by Kawamori Shoji – creator of the Macross franchise – Watanabe was chosen to co-direct a new OVA for Macross, Macross Plus. The project consisted of a 4-episodes series. The plot took place 30 years after the events of the original story.

As a creator working on an already-established universe, Watanabe lacked complete creative freedom. The weight of a well-known franchise is something to carry on. Despite its limits, the project showed ideas later developed in the director’s catalogue – such as the use of non-common music for anime at the time. The overall result was a success, commercial and critical. In retrospect, it defined sci-fi animation in the 90s.

[This is the first anime show to incorporate CGI in traditional animation. Love it or hate it]

Moreover, Macross Plus was a project where young creators could meet future collaborators. People indispensable to create Cowboy Bebop formed the staff for this OVA, collaborators, same as the music composer Yoko Kanno and the screenwriter Keiko Nobutomo.

To Be or to Not…To Bop.

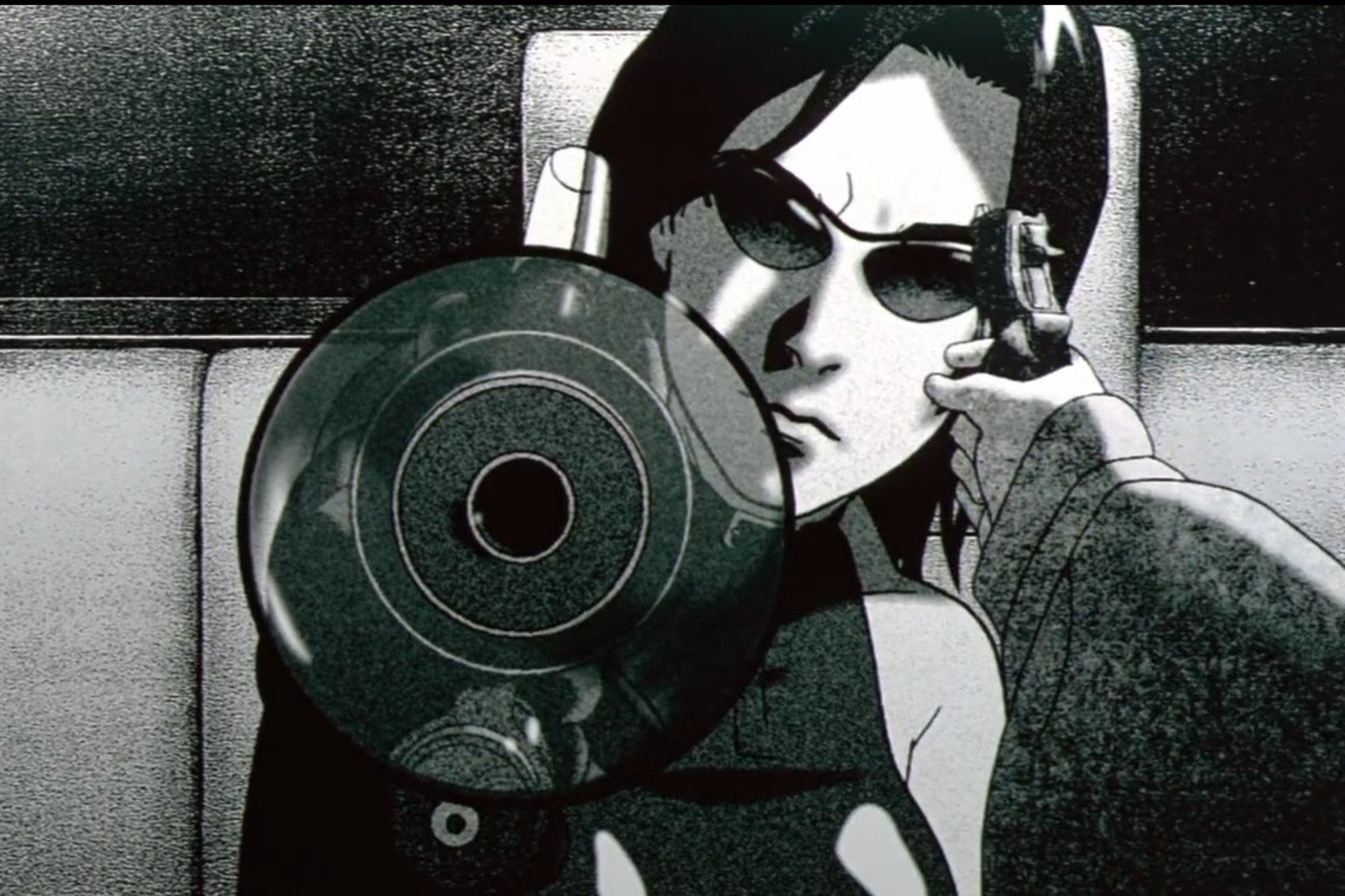

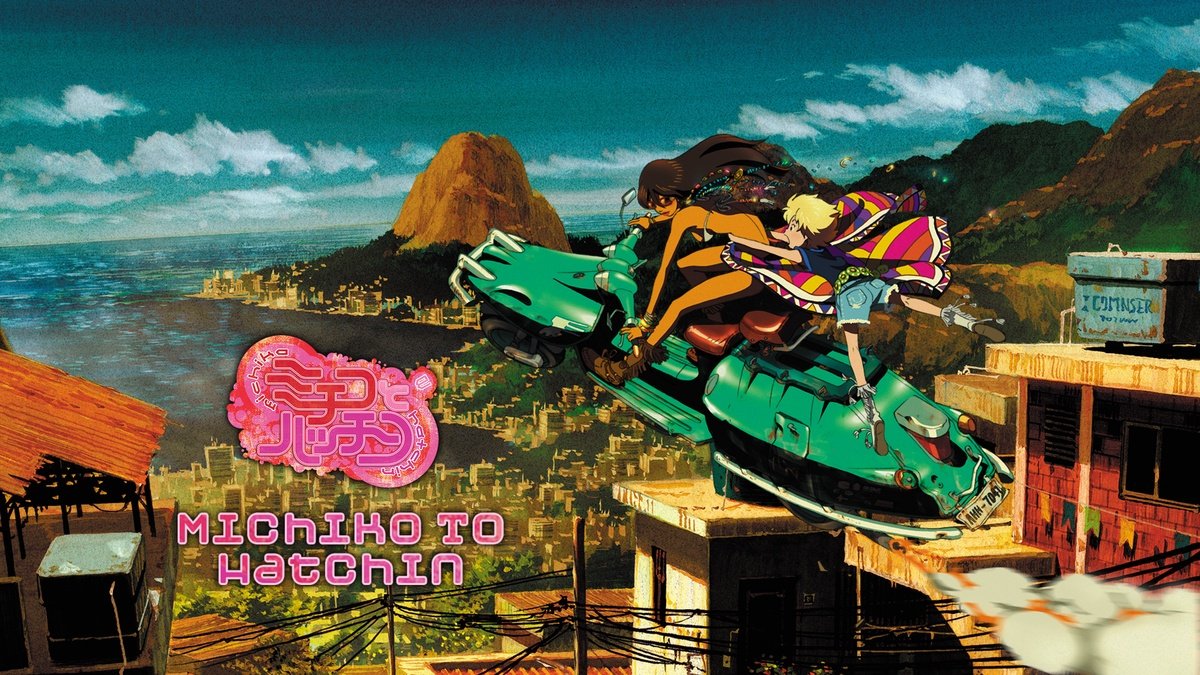

Cowboy Bebop [1998] is the first extended stop in our three-part project. The show takes place in the year 2071. Because of a massive accident on planet earth, humans colonized the Solar System. As the crime rate becomes uncontrollable, bounty hunters deal with fugitives.

In 26 episodes, we follow the story of four bounty hunters – and a dog – travelling through space to capture criminals. The iconic crew consists of the enigmatic Spike Speigel, the reasonable Jet Black, the amnesiac Faye Valentine, the genius hacker Edward Wong and a super-intelligent corgi dog named Ein.

After 20 years of its premiere, Cowboy Bebop holds a special place in the anime community. Acclaimed by critics and loved by the fans, the project is an elementary principle for Japanese animation culture. Its impact remains in the use of music and anime production. But before jumping on these topics, we must ask: what is Bebop?

Bebop is a style of Jazz develop in the 1940s. It is known for sophisticating Jazz. Some of its characteristics are fast tempo, rhythmic patterns, spontaneity, and improvisation. But also, intricate harmonies and numerous changes of keys.

In a scene stuck by overly commercialized Jazz, Bebop is a fruit of musician tired of the current status of the genre. Styles like Swing and Big Bands repeated musical formulas proposed twenty years before. As an opposition to the limits of appealing mainstream audiences – white mostly, this new style stripes off from its danceability to achieve complex musical forms.

This ‘musician’s new music’ was born in the Harlem, New York nights. Jazz players reunited in clubs to improvise and compete with each other. These events were called Jam Sessions. To this day, these nights are a symbol of liberation of commercial ties - alongside pushing the genre forward.

If you want to hear some Bebops recordings, we highly recommend you Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonius Monk, among others.

In regards to the Cowboy Bebop universe, you may notice some connections between Bebop history with the show. One of the more notable associations – aside from the name of the anime – comes from the opening song ‘Tank!’ and its famous starting phrase ‘1, 2, 3, Let’s Jam’. As a symbol of improvisation and audacity, the concept of jamming hides a deeper relation to Cowboy Bebop, and it has a lot to do with how the production process was – a dance between Watanabe and his collaborators.

The team behind the show consisted of composer Yoko Kanno, screenwriter Keiko Nobumoto, character designer Toshihiro Kawamoto, and mechanical art designer Kimitoshi Yamane.

Unlike many other animation directors, Watanabe lacked abilities in drawing. For him, a team to count on was a necessity. The director even saw an opportunity in this handicap:

“I learned from him [Ryousuke Takahashi, a fictional character from Urusei Yatsura: Beautiful Dreamer] that I shouldn’t rely solely on my own ability to create – I needed to learn to rely more on my staff and their abilities, all while fostering their skills at the same time”

From this perspective, the director’s role is more about consolidating and direct a group of creators than imposing his vision. And so, Cowboy Bebop isn’t a one-man’s show but a conversation between many creative forces. The work between Yoko Kanno and Shinichiro Watanabe is a perfect example.

Yoko Kanno is a brilliant mind by herself. Born in Sendai, Japan, she is the mastermind behind the impressive soundtrack of many of Watanabe’s anime series. Since she was a child, she was instructed in musical education, taking classes of piano and organ. While growing up, her parents only allowed her to listen to classical music – cutting her off from manga, films, anime, and other forms of popular culture.

The discovery of non-classical music came as a heavenly revelation. A friend introduced her to rhythm and non-classical forms of music.

[Strangely, this is the plot of another Watanabe’s anime Kids on the Scope; a square-minded classical musician discovering Jazz through a friend]

This eye-opener moment led to Kanno’s decision to pursue music as a career.

Few years after this revelation, Kanno decided to travel through the United States with one goal: seek the ‘essence of music.’ With little money and only by bus, the composer crossed the US from coast to coast, looking for music and new sounds. From listening to children playing the drums with cans to experimenting with real jazz players; everything was a source of learning new skills for her. The things she learned throughout her journey would accompany Kanno in her later works.

Before Cowboy Bebop, she was producing soundtracks for several videogames and other anime production. She met Watanabe in the Macross Plus project. Impressed by the talent of Kanno, the director proposed another collaboration.

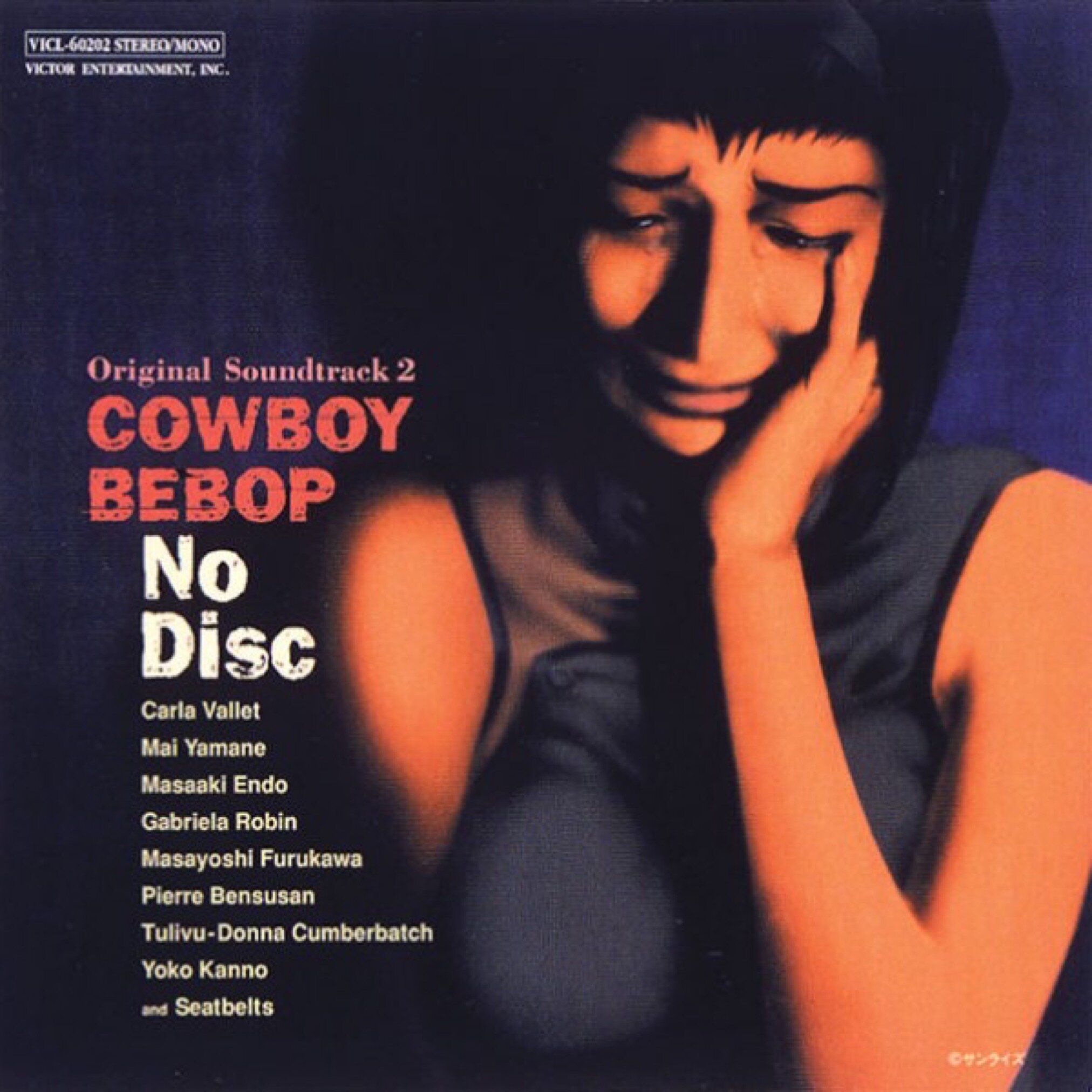

The work produced by Yoko Kanno in Cowboy Bebop is incredible. To this day, remembering the show without its eclectic, profound, and energetic soundtrack is a vane intent. Luckily, there’s a lot more to digest than the iconic opening score ‘Tank!’

Anomaly, before visual production began and the screenplay was complete, Kanno already was working on the soundtrack. Based on a previous conversation with Watanabe, the composer created new pieces that reflected the show’s vision. Thanks to the equal admiration and respect, both creators jammed and improvised based on each other’s work. Watanabe made visuals based on Kanno’s music, and Kanno made music inspired by Watanabe’s visual.

To accomplish the enormous task of recording the soundtrack, Kanno formed a band that could perform the sounds she heard in her mind: the Seatbelts. The name is a reference to a scene of Cowboy Bebop, where – for their safety – the musicians are asked to wear seatbelts while performing Jazz. Together they record the four albums that musicalized Cowboy Bebop.

Production-wise, Cowboy Bebop was completely unorthodox. As anime series are expensive products, they are an investment. A project needs to assure success with a plan. Cowboy Bebop does the opposite; it presented an original story – it wasn’t a best-selling manga adaptation – and allowed improvisation in the making. A producer’s nightmare.

As more music popped up, new animated sequences appeared. The final result was an explosive soundtrack that dances freely between an absurdity range of sounds. From rock to jazz to metal to pop, Kanno became a chameleon who could easily encapsulate Watanabe’s vision.

Let’s take the original song ‘Rain’ from in the fifth episode Ballad of Fallen Angels. As Spike enters a gothic church to meet Vicious, his opponent, we hear an organ playing with a Steve Conte singing ’walk in the rain / why do I feel so alone / for a reason I think of home’ followed by a guitar solo. Listening to this gets in our feelings.

Many of the scenes in this sequence appeared before Kanno produced its music, and is the perfect example of how music, writing, and animation merge into a final product superior to the value of individual pieces.

Cowboy Bebop revolutionized in plot structure as well. While many 90s anime shows used arcs as a medium of storytelling – various episodes compromised with a background story; Cowboy Bebop constructs an episodic experience. Each episode is a self-contained story told within 24 minutes.

In a way, we can say that every episode is a session that contains its atmosphere, locations, characters, climax and music. Few times this rule is broken, specifically at the end of the series where the show is urging to close the development of characters. But aside from this, the show can be consumed with no specific order.

The lack of continuation through episodes makes the show a compilation of short movies. Strangely, this was key to its success in the western world. Since there’s no necessary relation between the episodes, kids turn on the TV and immediately connect with the adventures of Spike, Jet, Ed, Faye, and Ein. No background context is needed.

Additionally, the anachronic structure is where Yoko Kanno’s border crossing mind shimmered. The soundtrack encapsulates Watanabe’s vision in every session. It doesn’t matter if the atmosphere needed abrasive metal riffs [‘Heavy Metal Queen’ episode] or melancholic tunes [‘Hard Luck Woman’ episode]. Kanno can play and stand out in any situation.

As you could expect, such an experimental show got cancelled at its first airing. Bandai Namco, the entertainment corporation that financed the project, only wanted a series to sell spacecraft toys. [Between the ’80s and ’90s, many shows only purpose was to sell merchandise to kids – He-man is a famous case.]

Bandai [initially] didn’t care what Watanabe created as long it had spaceships. The problems began when they realized that Cowboy Bebop was an adult show. The narrative unhurried and mature, the characters faced existential questions, and people died; all these factors didn’t favour selling toys.

Cowboy Bebop dropped out of TV-programme after only 12 episodes and a special episode. Many people don’t know about this hidden special episode]. Fortunately, Watanabe’s project received the financing necessary apace with full creative liberty.

Nowadays, it's hard to call something a masterpiece. Is it something perfect, outstanding, or overwhelming? Moreover, ‘hype culture’ seems to distort our criteria – everyone wants to make a value judgment as soon as possible.

Although Cowboy Bebop is outstanding and overwhelming, it could be called a masterpiece for other reasons. The show innovated animation culture. Either daring soundtrack, improvisation behind its production, storytelling structure, or mature and profound characters, the show became a new genre in itself.

And here’s a thing: hidden in the opening sequence, and in some commercial break visuals as well, Watanabe placed the manifesto that elucidates the thinking behind the Cowboy Bebop project:

“[…] They are sick and tired of the conventional fixed style jazz. They’re eager to play jazz more freely as they wish then... in 2071 in the universe... The bounty hunters, who are gathering in the spaceship “BEBOP”, will play freely without fear of risky things. They must create new dreams and films by breaking traditional styles. The work, which becomes a new genre itself, will be called... COWBOY BEBOP’”

Beyond our initial thoughts, Cowboy Bebop is an open letter to creators. It expresses how over-commercialized forms of art put a ceiling on our thinking. But even better, it gives us a hint about where innovation relays.

By looking through Jazz and Bebop history, the director incorporated new notions into his work – jamming, sessions, and improvisation are vocabulary from the Jazz world. The brilliance of Cowboy Bebop remains in how, using arguments from another field [music], Watanabe rethought where the limits of animation were.

Macross Plus ends with the following epigraph ‘dedicated is to you, our future pioneers.’ Thirty years later, creators of any kind – designers, artists, or musicians – can look up to Cowboy Bebop and reflect among the same things jazz players did in the 40s: how to pioneer.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lucas Moreno is an architecture student based in Santiago, Chile. He specializes in history, critic, and theory of Architecture.