WHAT ARE YOU RUNNING FROM? AN INTRODUCTION TO RACING ANIME

In a medium as intimidating, and vast as anime can be, there is nothing more exciting than a series of titles that remind you exactly why you love it.

Every now and then a phenomenon comes along that takes the beloved, pre-conceived tropes of the industry, pours gasoline on them, and sets it ablaze. One such phenomenon is that of racing anime. This subgenre is not only tonally distinct in its artistry, but also incredibly consistent in the quality of its storytelling.

At times overly produced, and at others acutely subtle, racing anime enjoys that sweet spot between action and emotion. Glassy, and breathless at the right moments, and then, in a second, neon and vibrant. These stories are as much about the nauseating races that define them as they are about the humanity of those behind the wheel. The racing sequences are indeed outlandish, tense and electric, but what really cements the genre’s identity are the moments of genuine introspection that punctuate them.

The characters of these stories utilise racing as an extension of themselves. Whether it be to escape their pasts, understand their presents, or carve out their futures, the act of racing is imbued with a metaphoric significance unparalleled in any other genre of anime. To give you a better understanding of the genre as a whole, as well as some pointers on where to start; we’ve compiled a list of some of the best titles to guide you on your viewing.

REDLINE

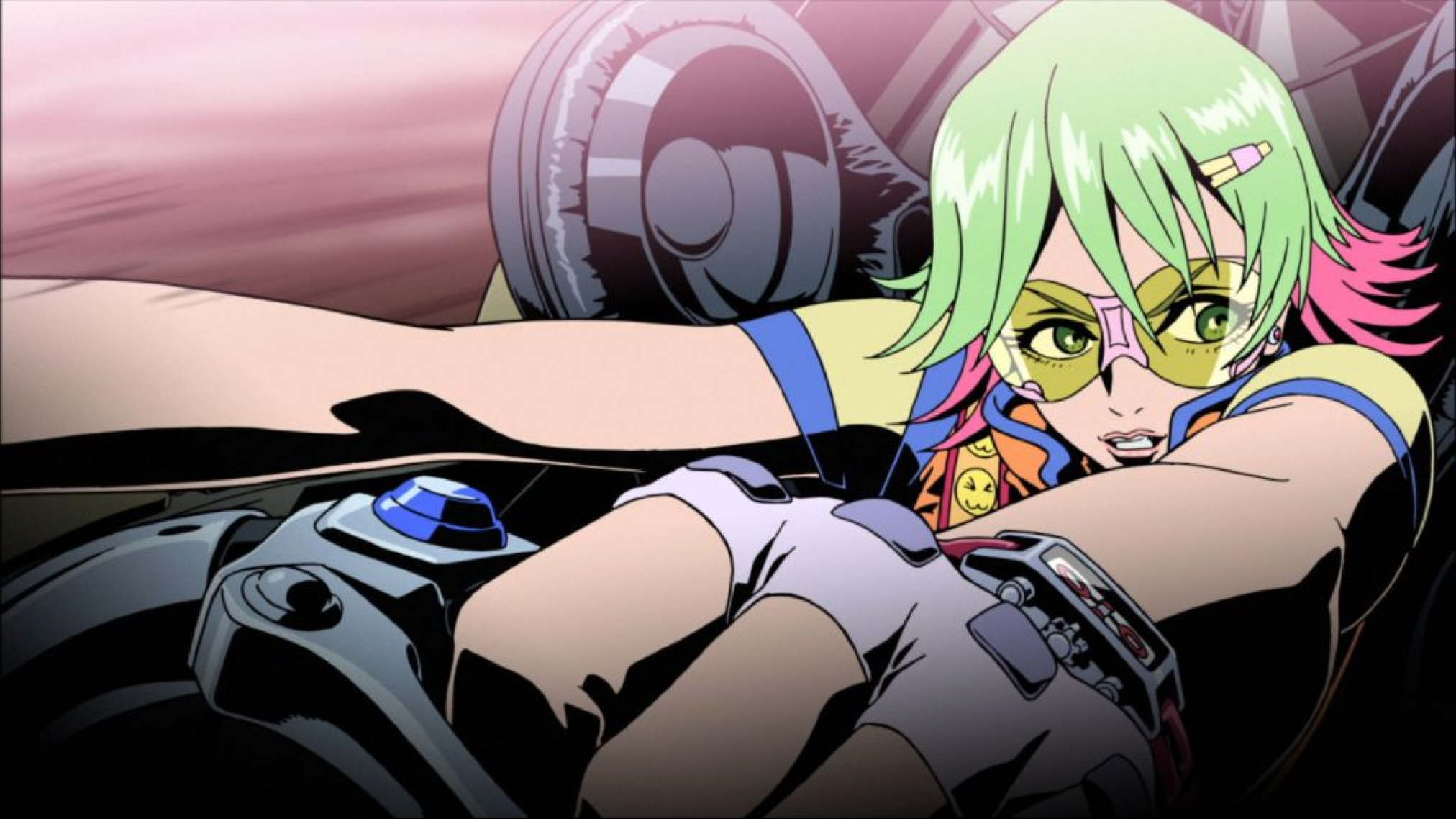

Redline is the kinetic, provocative fever-dream of Takeshi Koike, a veteran of the industry renowned for his work on classics such as Kawajiji’s Wicked City. Released in 2009, Redline serves as his directorial debut; yet, despite being Koike’s first florray in the driver’s seat, there is a sheer, relentless control to his visual storytelling. The film, in its purest sense, is a space opera, set against the backdrop of the most dangerous, exhilarating, illegal racing exhibition to ever grace the galaxy. Redline is indeed a visual, and auditory feast, yet there are noteworthy moments throughout its compact 102 minute run-time whereby just as the audience readies itself for euphoric pay-off, Koike chooses instead to cast our gaze inward, and offers a deeply compelling interrogation of the very act of racing itself.

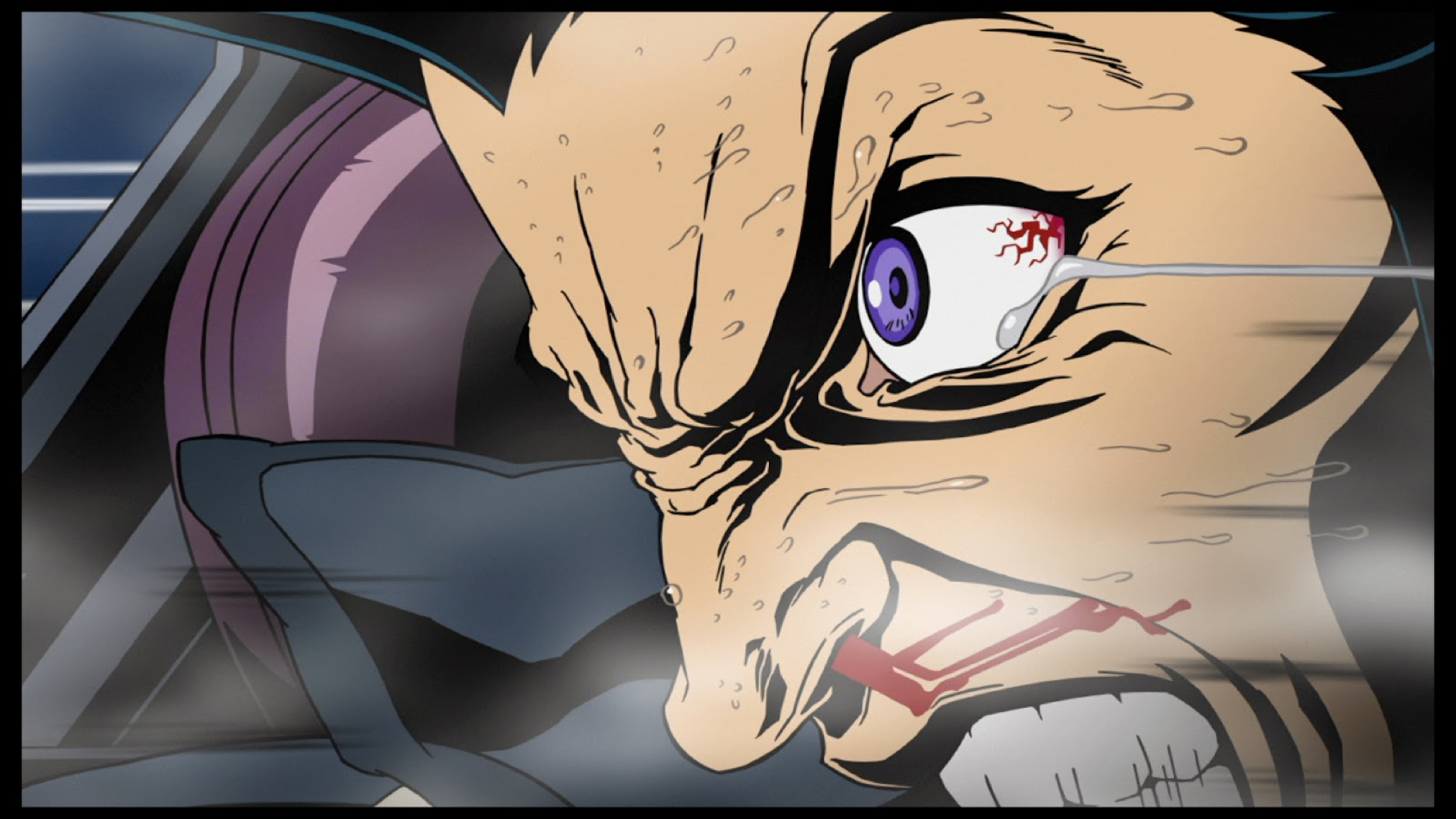

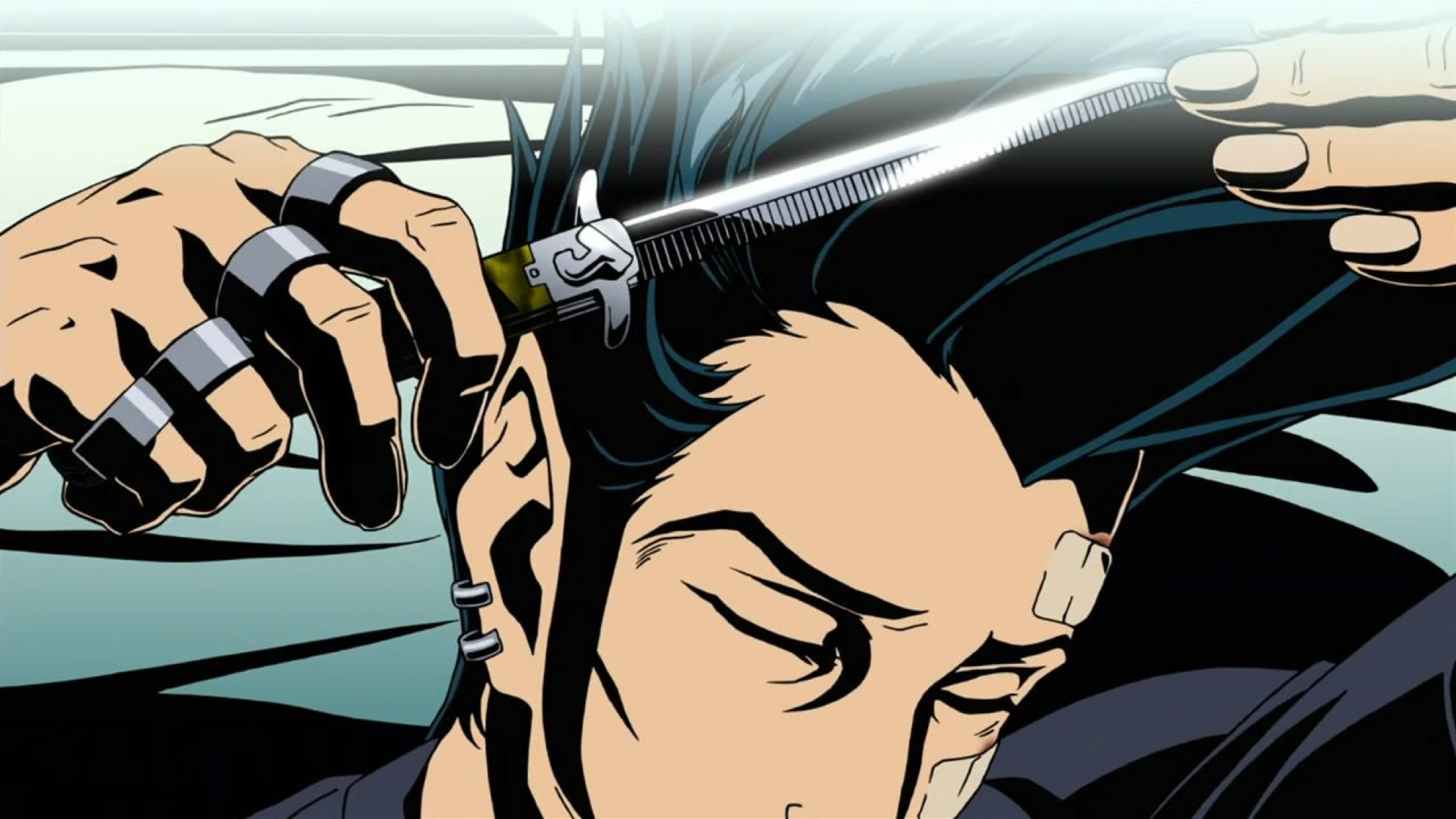

Koike is a master at distorting the depth of field to give a real sense of the raw physical velocity, and pressure faced by both the vehicles, and the lunatics that wield them. Engines roar, pupils dilate and tires screech as the racers surge through the dystopian wasteland Redline calls it’s home.

The warped visuals are in no small part supplemented by an incredible soundtrack that pounds with an energy, and elation akin to that of the racing spectacle itself. The surprising mix of effervescent disco, and joyful electronic rock are woven seamlessly into the chaotic visual language that ebbs and flows on screen.

There is a delicate momentum in the way Koike leverages this soundtrack; freezing and burning the onscreen visuals all at the once. It heightens the moments of intensity; rising until it crackles with heat, and just before the film sonically combusts, it ices out, leaving the audience in silence just before ramping up the intensity once more. These moments of audible blackout throughout the film completely disrupt the audio-visual link for the audience; something uniquely irresistible to Koike’s Redline.

The film is a love-letter to speed, momentum, and velocity, just as much as is to the propulsive motivations that drive one to race. Every 5 years, the greatest racers from every corner of the galaxy gather to risk their careers, reputation, and ultimately, their lives to compete for the glory of the Redline. Our protagonist, Sweet JP, is one such risk-taker. Throughout the film, we accompany JP during moments spent in memory, and get a real sense as to what racing means to him personally. Koike is a director fascinated by the alluring masochism of speed, and the innate dispositions of those who long for it.

Redline is a film inundated with character cut-aways, and these jarring close ups grant us brief, glancing echoes into their unresolved pasts. While no one racer is offered the spotlight for any extended period of time, the moments we do get to spend with the cast are significant, and deeply personal. These flashes of humanity recontextualize the race; framing it less as a grand prix and more as a microcosm of human psychology. What initially may have appeared as a predictable racing narrative caves in, revealing a network of branching, personal motivations, and desires, with the race at its beating core.

The significant, personal weight each character imbues the Redline with provides a startling observation of the film’s world; as if nothing else in the universe holds as much importance. As such, the race becomes something entirely different for each character. In this way, Koike’s Redline succeeds in conveying the recurring motif that binds the films of this list; racing is ultimately about the humanity of the person behind the wheel.

The Redline exudes a significance on both a micro level for each character, but also on a macro-level, for the world at large. There is also an unmistakable, political motif threaded through the under-belly of Redline’s narrative. Roboworld, the site of this year’s Redline, is an oppressive, militant planet, completely opposed to the event, and the galaxy-wide attention it garners. For their own safety, the racers are housed on Roboworld’s satellite moon, Europass, a demilitarized zone signed away to refugees. Redline is a film bolstered by these subtleties, and Koike’s universe shimmers with the complexities, and nuances of human life.

There is a quiet precision, and exactitude to the way Koike’s characters navigate the world of Redline, and this is a testament to the painstaking animation that was involved in the film’s production. Drawn over 7 years, and consisting of more than 100,000 frames, Redline is more than a simple passion project, but the product of years of devotion to create a wholly, singular experience. Koike’s labour of love succeeds in bringing to life a cast of characters teeming with imperfection, and nuance framed amid an extravagant, indulgent racing phenomenon. Redline is truly not to be missed!

NASU: A MIGRATORY BIRD WITH SUITCASE

Kitarō Kōsaka’s Nasu franchise is to cycling what Koike’s Redline is to intergalactic drag-racing. Adapted from the 3-tankōbon manga by Iō Kuroda, the Nasu cinematic universe is explored across two feature length films; Summer in Andalusia (2003), and it’s more poignant sequel, A Migratory Bird with Suitcase (2007). For the purposes of this article, we will be diving into the 2007 sequel, but both films provide equally sentimental, and passionate examinations of cycling, and as such, should be considered with the same reverence.

Kosaka’s A Migratory Bird with Suitcase is a film with an uncompromising point of view. From it’s opening moments, there is a clear metaphoric certainty that cycling, the presumed thematic driving force of the film, is much more than a physical activity. Our protagonists, Benengeli and Ciocci, of the Pao Pao Beer cycling team, are blindsided when their hear of the the suicide of their hero, Marco Rondanini. Death should not be considered the central theme of the film, but as the thematic catalyst which sends Ciocci into a spiral of introspective self-reflection, and critical re-examination.

In its literal sense, the theme of death can be abandoned in favor of it’s more literary interpretation; that of catharsis and renewal. Ciocci’s world begins to fragment when he is accosted the reality and implications of Rondanini’s suicide. As such, the film calls into question the morality of the pursuit of success. Does one cycle to win, or to escape from something they cannot face? In this way, Kosaka’s Nasu provides a startling exploration into racing as a form of escapism.

The motif of escapism is something which Ciocci becomes cognisant of throughout the film. Competitive cycling is a rewarding, yet brutal activity. In spite of this, the cyclists of the Pao Pao Beer team endure the extreme pain and suffering with a sure-fire determination; almost as if they are punishing themselves for their existence.

The self-sacrifice, and devotion that it requires to become a competitive cyclist leaves no room for life; something grimly portrayed in Ronandini’s death at the beginning of the film. Without cycling, what do the characters of Kosaka’s Nasu have left? Without suffering, how can they tell that they’re truly alive? Ciocci himself likens the act of cycling to that of navigating life, with perhaps the most poignant line of the film:

“The first thing we were told when we entered this world was “don’t think about anything but suffering””

There is an elegant ambiguity in the uncertainty of whether he was referring to the world of cycling, or indeed, our world at large.

Furthermore, the film captures beautifully the loneliness of racing. Similar to Redline’s use of cut-aways, Nasu indulges in first-person perspectives at the fever-pitch of it’s racing sequences to truly capture the isolated, solitary experience of being in first-place. These shots supplement Ciocci’s own journey towards happiness in an incredibly poignant way. While his contemporaries are racing to win; or moreso, living to win, Ciocci simply wants to race, and to live.

Parallels can be drawn between Ciocci’s struggle and that of Plato’s allegory of the chariot. According to Plato, man is being drawn in a chariot by two opposing forces; emotion, and instinct. In Ciocci’s case, his instinct is to win, while his emotional drive is to simply live his life. Throughout the film, we see him wrestle with these conflicting compulsions. It cannot be denied that this struggle is a unifying human experience; something which frames the film as perhaps the most poignant racing anime out there.

Kosaka’s A Migratory Bird with Suitcase charts one man’s desire to live his life on his own terms, instead of letting it be controlled by the allure of the “race”. The film beckons its audience down a more mournful, sentimental avenue of the racing anime genre. However, between its more meditative moments are thrilling, and riveting sequences which capture perfectly the intoxicating allure, and competitiveness of a cycling exhibition. If you’re looking for a racing anime with a philosophical overtone, this is your best bet.

INITIAL D

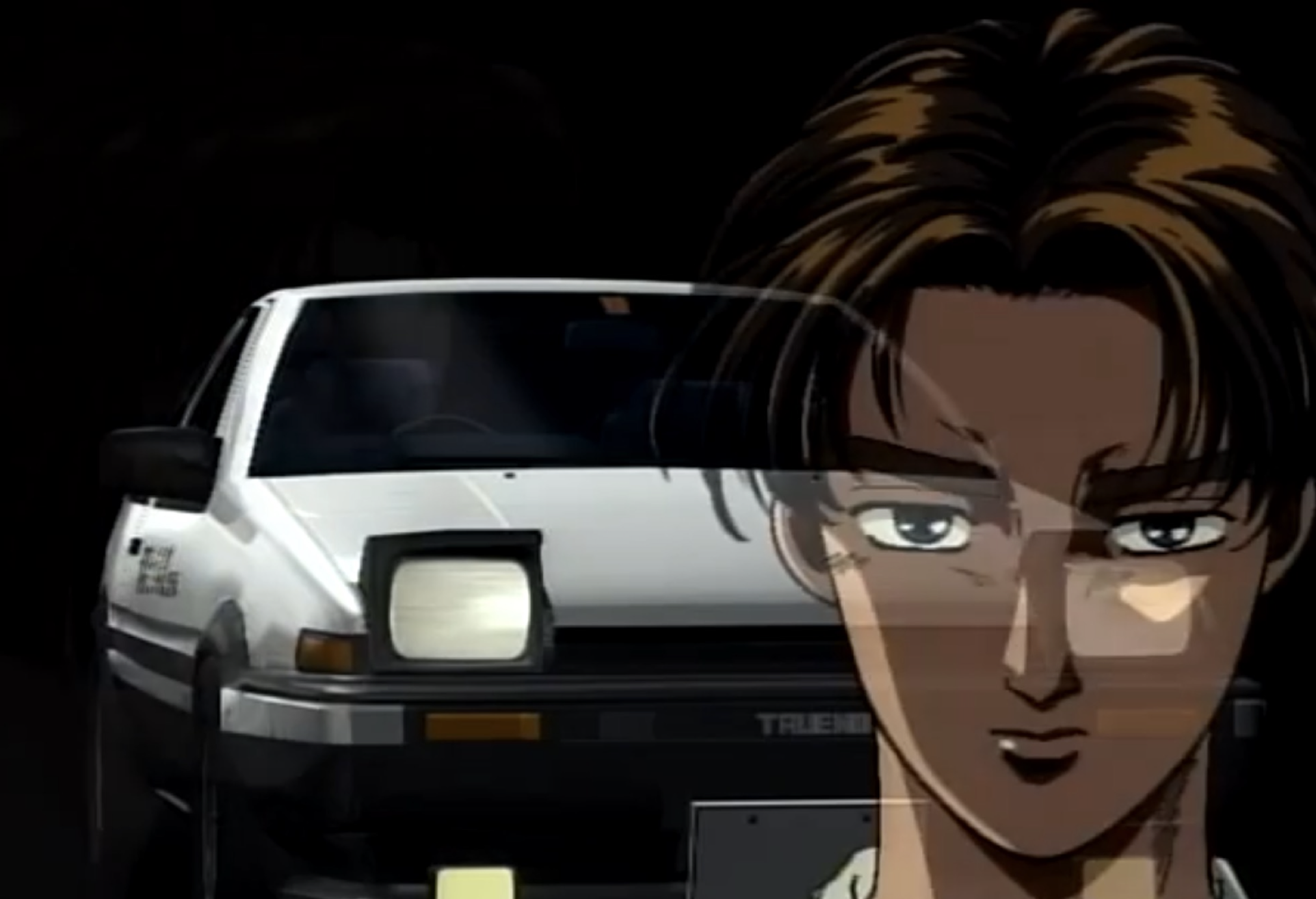

No racing anime list would be complete without reference to Shin Masaki’s legendary 1998 animated series, Initial D. Spawning more than 5 series, and an additional 4 feature length films, the Initial D franchise is undoubtedly a cultural touchstone for Japan. And yet, it’s visible legacy overseas is criminally understated. Adapted from the 48 volume manga, Initial D tells the story of Takumi Fujiwara, a student turned tofu delivery driver, as he navigates the underground subculture of street racing that dominates the nightlife of his coastal town of Akina.

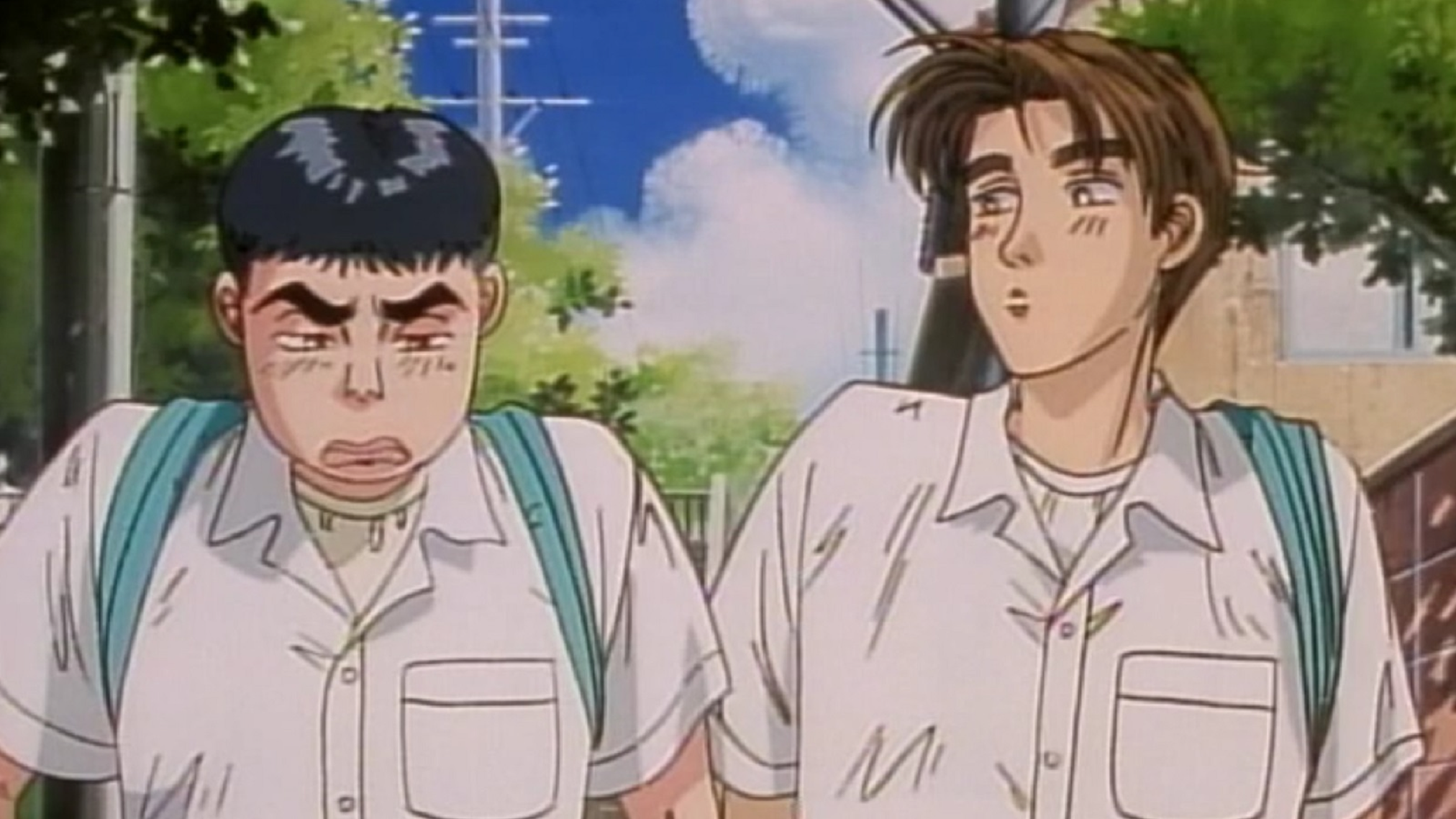

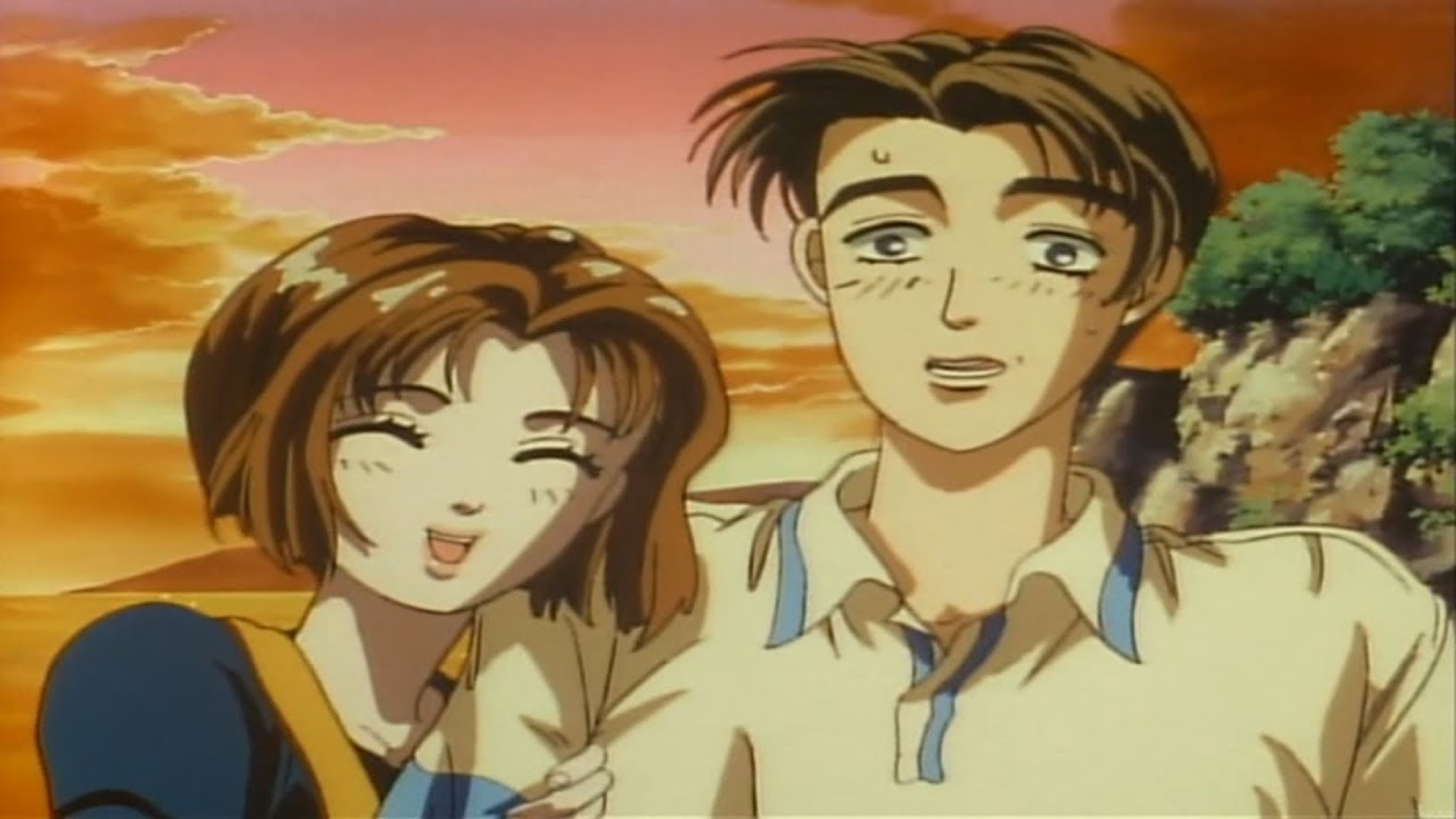

Masaki’s series is teeming with the subtleties, and vibrancy that define 90’s anime; the warm hum of Summer cicadas, the swooping haircuts, and a cast of upbeat teenagers coming-of-age. Indeed, youth is a central theme of Initial D’s story, one in which street-racing doubles as both a literary device to chart the maturations of its characters, but also a tool which the cast of Initial D leverages to pave their own paths toward adulthood. As such, Initial D provides a metaphoric observation of racing as the passionate, adolescent need to be remembered.

This notion of legacy is something which characterizes much of Initial D’s cast. As such, street racing becomes the recurrent, undisclosed link which binds the citizens of Akina. Everyone is aware of what happens after nightfall, and yet, there is a sense that this knowledge is not something inherited, but a rite of passage that each of Akina’s youths must discover for themselves. As the next generation of racers ascend to the battleground of Mt. Akage, there is a resurgence of energy in the small coastal town. Daily life suddenly becomes fixated entirely on the oncoming Saturday; in which Mt. Akage will light up with the glare of taillights, and the screech of tires. Street racing seemingly becomes the only thing worth living for, thus capturing perfectly the singular obsessiveness of youth.

Through Takumi, the audience learns of the Akina SpeedStars, and their simmering rivalry between the RedSuns which has been passed down to them by the previous generation of racers. Despite being adversaries, antagonism between opposing sides is never indulgent, or extreme. Between moments of jealous outbursts are genuinely touching exchanges of respect, and admiration, as well as a mutual reverence for the art of street racing. This sense of frenetic comradery is symptomatic of the turmoils of boyhood, and serves as the cohesive ribbon which ties much of the story, and it’s characters together. Takumi and his contemporaries are at the precipice of adulthood; navigating school-life, hunting for summer jobs, and flirting with girls.

However, whatever anxiety or confusion they experience during the day is abandoned entirely in their midnight pursuits. Behind the wheels of their cars, the characters of Initial D are in complete control of themselves, and their lives. In this way, racing becomes an almost meditative experience - allowing the characters to reflect, and decide for themselves the type of person they want to become.

Masaki’s Initial D is a product of its time. The anime drips with a style unique to the late 90s, as creators looked toward the millennium for inspiration. CGI is leveraged heavily during the show’s tense racing sequences, and despite being reminiscent of early PlayStation graphics, Masaki’s stylistic choices contribute heavily to the enduring reverence the show elicits. The jagged, robust models shift, and barrel down Mt. Akage, and while these shots may not be the most aesthetically pleasing in anime, there is an inherent admiration for a director and their determination to carve out their own style.

As if standing on the precipice of the millennium, Masaki reaches into his own fabricated tomorrow and draws from it the innovation, and technique that he perceives to be the future of all media. In retrospect, however, in the 20+ years since Initial D’s release, anime never fully embraced this avenue of visual storytelling. As such, consuming the anime in the present day makes for a truly exciting, and hopeful watch; as if the limit of anime is only the imagination of the director.

Initial D’s legacy is renowned, and omnipresent in the Japanese cultural consciousness. It captures perfectly the period in one's life where they are eternally grounded in the present; nostalgic for a past they can never again experience, and hopeful for a future that has yet to come. Street-racing becomes both the source, and product of much of these character’s experiences in the small town of Akina. Experiences fuel one’s identity, and this is no more apparent than in Initial D’s 23 episode arc. Takumi, and his fellow racers are the perfect surrogates for the audience to reflect on their own motivations, and desires. Initial D is ultimately a beautiful meditation on racing as metamorphosis, abandoning the question of “what are you running from?” in favor of the more poignant “what are you running to?”. Bolstered with a variety of life lessons, and a style that shines with the glare of tomorrow, Initial D should be on everyone’s watch list!

Conclusion

In many ways, racing anime is the murky moving inkblot of the medium. Just when you think you understand what you're seeing, it shifts, changing form and structure, ultimately becoming something new. On the surface, these titles have all the bombastic, pompous appeal of a Hollywood blockbuster, but on closer inspection, there are deep, profound avenues of thought, and contemplation threaded throughout. There is a compelling subversion of expectation taking place here; where there is a perspective gained instead of an assumption fulfilled. The physical act of racing, that of propelling oneself forward at full speed, is the ideal mechanism for these directors to exact their stories of flawed, incomplete characters outrunning the very thing that pursues them. Whether it be one’s past, a feeling of inadequacy or the fear of an unfulfilled life, there is always a sense that these anxieties are slowly catching up with these characters, steadily encroaching in the rear-view mirror. Indeed, these very fears are the driving motivators that propel our characters to strive for first place, as if the answers to their questions reside behind the finish line.

The genre of racing anime is brimming with these narratives, and the hues of storytelling stretch far beyond even the titles mentioned in this list. Nevertheless, the next time you consider watching an anime, we implore you to consider racing as the genre du jour. A word of advice though, if you do find yourself in the driver's seat, strap in, and prepare for the ride of your life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Based in Dublin, Kieran Enright writes about all forms of art, media and culture that exist on the fringes of society.